By Tashia Roberson-Wing, John R. Lewis Social Justice Fellow

Introduction

Black youth and families are disproportionally impacted by child-serving systems, including the child welfare, child protection, and juvenile justice systems in America.[i] Undeniably, racism and racial bias are the leading cause of Black families being overrepresented in the child welfare and foster care system.[ii] Black youth, compared to white youth, on average, spend a longer time in foster care. Being placed in foster care can be a traumatic experience that can make foster youth vulnerable to poor outcomes in adulthood, such as homelessness, incarceration, and teen pregnancy. Historically, Black youth have been impacted by disproportional school disciplinary rates and criminalization. Being a part of the foster care system adds complex risks for Black youth and the existing injustices they face.

The Children’s Bureau (CB), housed within the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) through the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), oversees the implementation and management of the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS). AFCARS is one of the national reporting tools that reports during each federal government fiscal year (FY) on children and young people in foster care.[iii] The latest AFCARS report was published in November 2022 and covers fiscal year 2021 (October 1 to September 30). On September 30, 2021, 391,098 children/ young people were in the United States Foster Care System.[iv] African American/Black children represented 22 percent of the foster youth population, with 86,645 in foster care.[v] With 13.6 percent of Black people representing the U.S. population and 22 percent representing the U.S. foster care system, it is evident that Black youth are overrepresented in the foster care system.[vi]

This capstone serves as a resource guide regarding Black youth within the foster care system. It explores the child welfare system, how historic federal child welfare legislation impacts Black families, and trends in outcomes for Black youth in foster care. The publication also serves as a tool to provide industry professionals, policymakers, community members, and families with insight on how to serve Black youth in foster care best. The capstone provides resources—presentations, books, podcasts, literature, and other educational forms— that readers can access.

What is the Child Welfare and Foster Care System?

Child Welfare

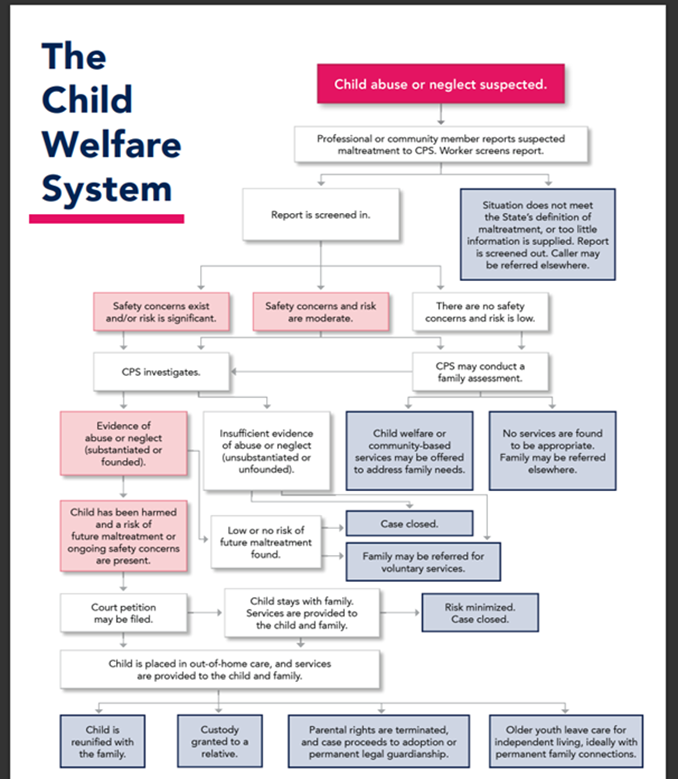

The child welfare system can be thought of as a group of services to ensure the well-being and safety of children, strengthen families, and promote permanency.[vii] Permanency can be defined as a legal, permanent family living arrangement in which the youth is either reunified with the birth family, living with relatives, placed in guardianship, or adopted.[viii] It’s important to note that the child welfare system is not a single institution or entity. The child welfare system may consist of public and private service agencies.[ix] The Children’s Bureau describes the child welfare system best as “public agencies, such as departments of social services or child and family services, often contract and collaborate with private child welfare agencies and community-based organizations to provide services to families, such as in-home family preservation services, foster care, residential treatment, mental health care, substance use treatment, parenting skills classes, domestic violence services, employment assistance, and financial or housing assistance.”[x]

Source: Children’s Bureau[xi]

Foster Care

The foster care system engages with families in crisis and children in need of services due to social problems.[xii] Foster care is intended to be temporary when a child’s caregiver cannot care for them, and the child welfare system intervenes. Children and families usually enter the foster care system when child maltreatment and unsafe conditions occur in the home. Maltreatment can be displayed in different forms, such as psychological abuse, sexual abuse, physical abuse, and neglect.[xiii] In FY21, the AFCARS reported that 63 percent of youth entered foster care due to neglect, 36 percent entered due to a parent’s drug abuse, 9 percent entered care due to housing instability, and 6 percent entered due to parental incarceration.[xiv] Child behavior problems, parental alcohol abuse, and the caretaker’s inability to cope are circumstances associated with a child being removed from their home and placed in foster care.[xv] It’s important to note that poverty can be mistaken for neglect. Arguably, children and families have been punished by separating the family due to the family being considered poor. Entering foster care, the goal is the same as other child welfare services: to obtain a stable, safe, and permanent home for the child—reunifying the child with parents, relatives, or adoption. Obtaining a permanent home for young people is not always the case, and some youth age out of the foster care system between the ages of 18-21 without gaining a stable, safe, and forever family. Typically, the aging out process involves youth who are deemed independent by their state and reach the maximum age to receive foster care service.[xvi] There are circumstances where youth age out of foster care due to being overlooked for adoption because of their age and stigmas.[xvii]

The History of the United States Child Welfare, Laws and Policies, and Its Impact on Black Families

History of Child Welfare

In the early 1800s, private charitable organizations and religious institutions primarily drove child welfare efforts. These organizations established orphanages and child asylums to care for abandoned, neglected, and orphaned children.[xviii] The history of the United States Child Welfare System can be traced back to the early 19th century when societal concerns about child abuse, neglect, and exploitation began to emerge. The system has evolved with various policies, legislation, and social movements aiming to protect and support the well-being of children.[xix] Federal legislation has played a vital role in the discrimination, harm, and overrepresentation that Black people have experienced navigating the United States’ child welfare system. To reduce harm, provide adequate resources for Black children needing services, and acknowledge Black families and children’s humanity, one must course correct by not repeating history. Understanding the history of the United States Child Welfare System can help society improve child welfare legislation in the future.

The Social Security Act

Currently, the largest source of federal funding for child welfare services is authorized through Title IV-B and Title IV-E of the Social Security Act (SSA). In 1935, the first set of federal grants for child welfare services was authorized through the SSA.[xx] The funding established through the Social Security Act of 1935, the original SSA, allowed states to create child welfare agencies and implement local programs to deliver child welfare services.[xxi] The Social Security Act of 1935 also established Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), later renamed Aid to Families with Depended Children (AFDC).[xxii] ADC was instituted to provide states with financial support for needy, dependent children.[xxiii] During the 1950s, mothers and needy children were denied ADC benefits under “suitable” and “man-in-the-house” policies[xxiv] Though there was a great need for ADC, benefit eligibility was determined by the mortality and worthiness of recipients.[xxv] Unsuitable recipients were often denied due to a parent being viewed as having immoral behavior or having given birth out of wedlock.[xxvi] Policymakers and those with authority used policy antics to “arbitrarily den[y][ADC] benefits to African Americans because their homes were seen as immoral, men other than biological fathers were identified as assuming care of the recipients’ children, the worker believed a man was living in the home, and/or the mother had children born out-of-wedlock.”[xxvii] In 1960, Louisiana disposed of 23,000 children from the ADC welfare program due to being cast as unsuitable.[xxviii] The majority of the children removed from the welfare benefit were Black. This removal is referred to as the Louisiana Incident, and it prompted the Flemming ruling.

The Flemming Rule was established in the 1961 amendments to the Social Security Act.[xxix] The Louisiana incident fueled the Department of Health Education and Welfare (DHEW) Secretary, Arthur Flemming, to rule that states had to see about children living in conditions declared unsuitable.[xxx] Under the rule, states had two options: 1. They could make the home/living arrangements suitable for children in need by providing appropriate child welfare services. 2. They could move the children to homes or placements deemed suitable while still providing financial assistance for the child.[xxxi] Since the Flemming Rule indicated that an out-of-home placement may be deemed necessary, a foster care component was established under Aid to Dependent Children within SSA.[xxxii] ADC-Foster Care allowed the federal government to match state funds regarding out-of-home foster care payments that supported children removed from homes considered unsuitable.[xxxiii] One could argue that the Flemming Ruling may have interfered with states denying welfare benefits on the premises of the parent’s marriage status but fueled states to remove children from “unsuitable” homes while providing services to foster caregivers rather than services to the family the child was removed from.[xxxiv] The SSA Public Welfare Amendments that became law in 1962 required state child welfare agencies to report children eligible for removal from their unsuitable homes to the court system.[xxxv] In the 1960s, the amendments increased foster care out-of-home placement cases throughout the United States.[xxxvi] In 1967, the SSA was amended again, making AFDC-Foster Care mandatory for all states.[xxxvii]

The laws that have come into place following the Louisiana Incident and the Flemming Rule have set a precedent for the harmful child welfare laws in-current-time that have disproportionately punished Black families and children today. The 1962 Public Welfare Amendments made the child welfare system another avenue to surveil and police Black bodies by requiring that “neglectful” parents be reported to the court system.[xxxviii] Black and Brown families experience poverty at higher rates than white families, putting them at a higher risk of being labeled as neglectful and having their children removed from their care.[xxxix]

The Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA)

CAPTA is a federal legislation that provides support and guidelines for preventing, identifying, and addressing child abuse and neglect and was first enacted in 1974.[xl] CAPTA provides a federal definition of child abuse and neglect—a guideline for states in creating their definitions and laws.[xli] CAPTA mandates that states establish procedures for reporting and responding to suspected cases of child abuse and neglect.[xlii] Teachers, doctors, and other service providers are mandated reporters and are responsible for reported suspected child maltreatment, which opens the door to investigating families.[xliii] CAPTA’s requirements further police Black families and create opportunities for biased reporting.[xliv] Research revealed that Black families, compared to white families, are more likely to be reported and screened by mandated reporters, proving that mandated reporting can be racially biased.[xlv] CAPTA requiring mandated reporting resulted in skyrocketing numbers of children being removed from their homes and placed in the foster care system.[xlvi] In 1974, there were 60,000 reports of suspected child welfare cases, and by 1990 there were two million suspected child welfare cases reported.[xlvii]

Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA)

ASFA marked a significant shift in child welfare policy. With the increase of children entering foster care at rapid rates in the 1970s came the issue of children staying in foster care for long periods. It emphasized child safety and permanency, prioritizing adoption over long-term foster care. It also set strict timelines for reunification efforts and promoted the termination of parental rights in some instances.[xlviii] The policy also shifted the focus from long-term foster care to timely permanency for children needing placement.[xlix] The Act significantly impacted the child welfare system by emphasizing timely permanency and adoption, promoting the well-being of children, and providing financial resources to support these efforts.[l] However, it also generated some debate and concerns about potential unintended consequences, such as the possibility of rushing to terminate parental rights without sufficient consideration of family circumstances and the potential for a disproportionate impact on marginalized communities.[li] The law has increased parental rights termination rates, drastically impacting Black families.[lii] Of all Black children in the child welfare system, one in 41 will undergo legal parental termination.[liii] When a child is adopted out of the child welfare system after the birth or legal parents’ rights have been terminated, they are considered a legal orphan.[liv] Today, Black children represent the majority of legal orphans.

The Multiethnic Placement Act (MEPA)

(MEPA), enacted in 1994 and amended in 1996, was established to ban federally funded child welfare agencies from using a child’s or potential adoptive/foster parent’s race, color, or national origin (RCNO) as factors to refuse, delay, or deny foster or adoptive placements.[lv] The target population was youth in the child welfare system and foster and adoptive parents. The Act intended to “decrease the length of time that children wait to be adopted; to prevent discrimination in the placement of children based on race, color, or national origin; and to facilitate the identification and recruitment of foster and adoptive parents who can meet children’s needs.”[lvi] The public problem stemmed from the amount of time youth, especially youth of color, were waiting to be assigned to adoptive placements or other adequate permanency placements. The idea of case workers insisting on race-matching placements and foster youth contributed to young people staying longer in the child welfare system.[lvii]

According to a statement released by the National Association of Black Social Workers, MEPA and the Inter-Ethnic Placement Act (IEPA) are “flawed because they were based on the incorrect assumption that African American children were disproportionately represented in the child welfare system because their adoptions were being delayed and denied because white people were being denied transracial placements.”[lviii] In 2019, over 50 percent of youth waiting to be adopted had been in care for over two years.[lix] Experts point out that foster youth of color are more likely to have extended stays in foster care leading up to adoption than their white counterparts. Black youth still have longer wait times to get adopted compared to their white counterparts. The number of transracial adoptions has increased for Black youth, while same-race adoptions have decreased.[lx] It’s important to note that foster care isn’t a long-term structure; every child deserves permanency and a stable home. Children also deserve cultural permanency and lasting ties to their culture and traditions. Arguably MEPA can hinder Black children from achieving cultural permanency if the law continues to use a color blindness approach.

Because child welfare is primarily handled at the state level, it results in variations in policies, practices, and terminology across different states in the United States. Through analyzing key historic federal child welfare policies, one can argue that the policies were never created to help Black families and improve the quality of life for Black families. Child welfare legislation has historically been centered around whiteness and a one-size-fits-all approach, resulting in Black people being deprived of adequate services, increased surveillance, and being criminalized for being poor.

Analyzing Trends and Outcomes Regarding System-Involved Black Youth and Black Families

Trends on the Front End

The child welfare system consists of policies and government entities that are set in place to protect children from maltreatment. Child maltreatment refers to children being victims of abuse and neglect. When maltreatment is suspected, a series of events occur, such as receiving a maltreatment report, investing the claim, determining if there has been an incident of maltreatment, and if the children need to be removed from the home.[lxi] These series of events are often referred to as the front end of the child welfare system. The front-end process contributes to the overrepresentation of Black youth within the foster care system. Compared to white children, Black children are reported for abuse and neglect at twice the rate.[lxii] Once maltreatment is reported, the reports must be screened to determine if the abuse or neglect legal definition has been met and if there needs to be further investigation.[lxiii] The chances of Black children having their report screened for further investigation is between two and five times more likely when compared to white children.[lxiv] By the age of eighteen, over 50 percent of Black children would have experienced a child welfare investigation,[lxv] and 18.4 percent of Black children, compared to 11 percent of white children, faced substantiated maltreatment cases.[lxvi] After the investigation and instead of receiving in-house services, Black children are 15 percent more likely to be removed from their families when compared to white children.[lxvii]

Racism is alive and well at the front-end process of the child welfare system. While the child welfare system is intended to strengthen families, it instead has historically dismantled Black families and caused harm.

The experiences that youth withstand while in foster care can serve as risk factors for poor outcomes and foreshadow their experiences within adulthood. Once Black youth are placed in foster care, they continue to undergo racial discrimination coupled with the experiences of being a part of the foster care system. Black foster youth are less likely to be reunited with their parents when compared to white youth in care. Black foster youth, compared to white youth, experience longer stays in foster care while experiencing more placements. Experiencing multiple placements can increase a youth’s risk of being incarcerated. In recent years, scholars have started exploring the foster care-to-prison pipeline. If a child involved in the foster care system has been placed in five or more placements, they have a 90 percent chance of being involved with the criminal legal system.[lxviii] The foster youth-to-prison pipeline is more likely to impact Black and Brown youth, youth with mental illness, and youth who identify as LGBTQ+.

Foster youth are subjected to higher rates of being human sex trafficked, risk developing poor mental health conditions, and are more likely to be treated with psychotropics compared to the U.S. general population youth.[lxix] Evidence reveals that youth placed in foster care are more likely to experience abuse than youth in the general population.[lxx] When considering the harsh realities and experiences that foster youth face, youth of color have a higher risk of experiencing these outcomes due to racial discrimination.

Not all foster youth are reunited with their parents or relatives, nor adopted—some youth age out of the foster care system. Aging out of foster care refers to youth who have reached an age where they begin to transition to adulthood and exit the foster care system. Youth who age out are more likely to experience housing insecurities, poor mental health conditions, employment and education challenges, and incarceration.[lxxi] When considering racial disparities within the child welfare system, Black youth who age out of care face an increased risk of withstanding poor outcomes.[lxxii]

Intersectional lens

Using an intersectional lens to understand the trends and outcomes regarding Black youth impacted by the child welfare system is important. Black girls, Black boys, and Black youth who identify as LGBTQ+ may have additional unique experiences based on their other marginalized identities. Further research is needed to understand how intersectionality may impact Black youth.

Overview of Black Girls’ Outcomes and Experience in Foster Care

Research conducted by the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality reveals that society perceives Black girls as more adult-like and not as innocent as white girls.[lxxiii] The study further explains that Black girls are seen as needing less nurture, protection, support, and comfort.[lxxiv] Scholars argue that the treatment of Black girls is due to the paradigms of Black femininity created during slavery that positioned Black women as “hypersexual, boisterous, aggressive, and unscrupulous.[lxxv]” Due to systemic issues, Black girls are still reaping the harms of these paradigms. The research concludes that Black girls experience adultification bias and are perceived as more independent by society, furthering the potential of aiding the disparities for Black girls in education, child welfare, and the juvenile justice system.

Research suggests that Black girls are overrepresented in the foster care system.[lxxvi] Black girls in foster care are also subjected to higher rates of residential and school changes, higher discipline rates, lower achievement rates, lower graduation rates, involvement in the juvenile system, and human sex trafficking.[lxxvii] At the same time, white children in foster care receive resources and treatment faster than Black children.[lxxviii] Adultification can affect how child welfare providers protect and serve Black girls, increasing disparities.[lxxix]

Black Foster Girls and Human Sex Trafficking

The Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, a nonpartisan organization, published a report on human sex trafficking regarding Black girls and women. The report revealed that Black girls in foster care are overrepresented and experience sexual abuse at a rate than white foster children.[lxxx] Regarding the inequalities in the foster care system, the report highlighted that the likelihood of Black girls experiencing poverty, disturbances in education, family instability and dislocation, and sexual and physical abuse is great.[lxxxi] Youth involved in child welfare, youth with abuse history, youth disconnected from education, and youth with family instability are among the most vulnerable for human sex trafficking.[lxxxii] Data pulled from Los Angeles County juvenile justice system identified 92% of girls involved in the system for trafficking as Black.[lxxxiii] Furthermore, out of 92% of the Black girl sex trafficking victims, 62% were from the child welfare system.[lxxxiv]

Black Foster Girls and Education

In general, data suggests that due to factors such as adultification bias, Black girls experience higher disciplinary rates for subjective infractions than white girls.[lxxxv] Girls in foster care face challenges such as abuse, teenage motherhood, juvenile justice involvement, and frequent placements that impact their academic achievement.[lxxxvi] Research further reveals that frequent placement moves require foster youth to change schools, affecting their ability to stay connected to the education system. Data demonstrates that 22.9 percent of girls in foster care are Black, yet 35.6 percent of Black foster girls experience 10-99 residential placements throughout their time in foster care.[lxxxvii] While many of these disparities negatively affect Black girls in society, unfortunately, little research focuses on the specific experiences of Black girls in foster care. All research indicates that more information is needed to understand Black girls’ experiences in child welfare. In addition to the experiences of Black girls in foster care, there is limited research available to analyze the experiences of Black boys and Black LGBTQ+ youth impacted by the foster care system. One study did indicate that LGBTQ+ youth are overrepresented in the foster care system.[lxxxviii] A survey conducted in Ohio’s Cuyahoga County showed that 32 percent of the youth that participated in the survey identified as LGBTQ.[lxxxix]

Best Practices and Resources for Serving Black Families and Youth in Foster Care

A network of individuals was asked to fill out a survey indicating effective resources that would help improve outcomes regarding Black foster youth and Black child welfare system-involved families. The network consisted of people with lived experience in the child welfare systems, industry professionals, policymakers, community members, and foster parents. The network was asked to identify resources they have witnessed beneficial when serving Black families and youth involved in the child welfare/foster care system. The resources fall into several categories: articles, literature reviews, presentations, social media platforms, podcasts, and books. The resources are also classified as program models, theories, best practices, and approaches.

| Articles, Literature, Toolkits, and Reports: | |

| Child Welfare Practices to Address Disproportionality and Disparity | An article aimed at industry professionals working with racially diverse families. The article offers insight surrounding the problems of racial disproportionality and disparity in child welfare. This resource can be used when serving Black families. How to access: www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/racial_disproportionality.pdf |

| 2017 Race for Results: Building A Path to Opportunity for All Children | The report, produced by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, measures education, health, and economic milestones across racial and ethnic groups. The report can be used as an educational tool for industry professionals serving Black youth. How to access: https://www.aecf.org/series/race-for-results-report-series |

| African American Grandfamilies: Helping Children Thrive Through Connection to Family and Culture | The toolkit, produced by Generations United, provides child welfare professionals and agencies with helpful tools to equitably serve and support Black families. The toolkit focuses on helping children stay connected with their family and culture. How to access: https://www.gu.org/resources/african-american-grandfamilies-helping-children-thrive-through-connection-to-family-and-culture/ |

| A Connectedness Framework: Breaking the Cycle of Child Removal for Black and Indigenous Children | The research article, written by Yvonne Chase and Jessica Ullrich, offers a framework that uses connectedness to create system change that supports Black and Brown children. The framework can be used as an educational tool for agencies serving Black families. How to access: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42448-021-00105-6 |

| Fighting Institutional Racism at the Front End of Child Welfare Systems: A Call to Action to End the Unjust, Unnecessary, and Disproportionate Removal of Black Children from Their Families | The report is a call-to-action to end racism within the child welfare system and practices that harm Black families and children. The report is produced by Children’s Rights. The report can be used by policy makers, agencies, and industry professionals serving Black families and Black youth impacted by the child welfare system. How to access: https://www.childrensrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Childrens-Rights-2021-Call-to-Action-Report.pdf |

| Interventions Relevant to Children and Families Being Served with Family First Funding that Have Been Shown to be Effective with Families of Color | The report, produced by Casey Family Programs, highlights the interventions that were funded through the Family First Prevention Services Act that have been effective in supporting families of color. The report could be used by policy makers, agencies, and industry professionals serving Black families and Black youth impacted by the child welfare system. How to access: https://earlysuccess.org/content/uploads/2021/11/FFPSA-Interventions-Families-of-Color_CFP_10-05-21_Executive-Summary.pdf |

| Books: | |

| You Are the Prize: Seeing Yourself Beyond Imperfections of Your Trauma by Amnoni Myers | A book that explores the author’s life growing up in the foster care system. Myers challenges readers to think about ways to help young people navigate tough transitions. The book sets out to remind people they are worthy no matter their experiences. This resource can be used for serving Black families, Black youth, Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: Amazon |

| The Black Foster Youth Handbook by Angela Quijada-Banks | A book that explores over 50 lessons the author learned to successfully age-out/transition out of the foster care system and holistically heal. The resources can be used as a tool when serving Black youth, Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: www.blackfostercareyouthhandbook.com |

| Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison | The author tells a story of a Black man trying to exist and survive in a racial divided world that does acknowledge his humanity. The resource can be used as an education tool for industry professionals and when serving Black families, Black youth, Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: Amazon Walmart Bookstore |

| The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B. DuBois | The book explores race, African American history, and the term double-consciousness. The resource can be used as an education tool for industry professionals and when serving Black families, Black youth, Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: Amazon Walmart Bookstore |

| Podcasts, Advocacy Platforms, and Websites: | |

| Diaries of a Black Girl in Foster Care | The podcast explores the intersectionality of being Black and a young woman and how identity poses a unique set of problems for Black girls in foster care. The Diaries of a Black Girl in Foster Care series that addresses current cultural issues, disparities, and stereotypes that aid in poor outcomes for Black girls who have experienced care. The resource can be used as an education tool when serving Black girls and Black LGBTQ youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: Apple Podcast Anchor Spotify YouTube Instagram: @blkgrldiariesfc |

| Resilient Voices & Beyond by Michael D. Davis-Thomas | The podcast is led by a Black man that is on a mission to help amplify the voices of those who were once silenced and aims to empower a new generation of foster care alum leaders. The resource can be used as an education tool when serving Black families and Black youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: Apple Podcast YouTube iHeart Podcast Facebook |

| Working With Black Families – Child Welfare Information Gateway Website | The website highlights resources and information when working with Black families impacted by the child welfare system. The website is a resource hub. The resource can be used as an education tool when serving Black families and Black youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/diverse-populations/black/ |

| Family Finding Website | Family Finding provides support for at-risk youth. The Family Finding Website offers endless resources and research to better support youth and families. The resource can be used as an education tool when serving Black families and Black youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: https://www.familyfinding.org/resources |

| Bright Spots | The Bright Spot website is a resource hub for parents. The website provides the best parent-reviewed practices and research. The resource can be used as a tool for agencies and staff serving Black families, Black youth, Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: https://findbrightspots.org/ |

| UpEnd Movement – Podcast and Advocacy Platform | The UpEnd Movement is a platform that focuses on strengthening and supporting children and families instead of separated and policing families. The platform offers a resource hub with resources pertaining to Black and Brown families. The resource can be used as a tool for agencies and staff serving Black families, Black youth, Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: https://upendmovement.org/ |

| A Key Connection: Economic Stability and Family Well-being – Website | Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago produced resources and research that addresses economic hardship and how it impacts child welfare involved families. The resource can be used by policy makers, agencies, and industry professionals serving Black families and Black youth impacted by the child welfare system. How to access: https://www.chapinhall.org/project/a-key-connection-economic-stability-and-family-well-being/ |

| Program Models: | |

| Structured Decision Making® (SDM) | SDM is an evidence- and research-based model for child protective agencies and child welfare staff. The model assist workers and agencies in promoting ongoing safety and well-being of children and in meeting their overall goals. The resource can be used as a tool for agencies and staff serving Black families, Black youth, Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: www.evidentchange.org |

| LifeSet | The LifeSet program helps foster youth transition to adulthood. The program model is an individualized, evidence-informed community-based program that provides youth with critical resources. The resource can be used as a tool for agencies and staff serving Black youth, Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: https://youthvillages.org/services/lifeset/ |

| Just Making a Change for Families (JMAC for Families) – H.E.A.L. Program | The H.E.A.L. program stands for heal, educate, advocate, and lead. H.E.A.L. is a 12-week fellowship program that is offered to parents impacted by child-serving-systems. The program provides a safe space in a community setting for healing and political education. The program encourages parents to play an active role shaping child welfare policy. This resource can be used for Black parents impacted by the child welfare system. How to access: https://jmacforfamilies.org/heal |

| Just Making a Change for Families (JMAC for Families) – S.T.E.P. | The Social Transitional Empowerment Program (S.T.E.P.) is a program for young people ages 18-24 impacted by the child welfare system. The program provides young people with a safe space to heal, skill building workshops, and advocacy training. This resource can be used for Black youth Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth impacted by the child welfare system. How to access: https://jmacforfamilies.org/step |

| Connect Parent Program | The program is a ten-week trauma-informed and attachment-based program for parents, foster parents, kinship caregivers, and other caregivers caring for young people. The resource can be used for Black families and Black caregivers impacted by the child welfare system. How to access: https://www.connectattachmentprograms.org/ |

| Culture Broker Program | The program is designed to raise and address concerns related to disproportionality and disparities that exist in the child welfare system, as well as concerns that involve issues of fairness and equity. Its mission is “Supporting the Power of Families to Strengthen Communities.”[xc] The resource can be used as a tool for the delivery of services when serving Black families and Black youth involved in the child welfare system. How to access: www.cebc4cw.org/program/cultural-broker-program/detailed culturalbrokerfa.com |

| Parents And Children Excel (PACE) | The PACE program has been proven to reduce racial disparities in Minnesota’s child welfare system. PACE serves as a diversion program for children of color. The program can be used by agencies and industry professionals serving Black families and Black youth impacted by the child welfare system. How to access: https://www.foster-america.org/blog/program-reduces-racial-disparity-in-child-welfare |

| 8 Steps to Promotion Workshop | The workshop is an eight-week program that prepares young people for adulthood and leadership. The program was created by a person with lived experience in the child welfare system. This resource can be used for Black youth Black girls, Black boys, and Black LGBTQ youth impacted by the child welfare system. How to access: Workshop (journieproject.org) |

| Nationally Recognized Organizations: | |

| Cut it Forward | Background: “Cut it Forward is a non-profit organization providing culturally specific hair and skin care resources for foster and adopted children of color, and their caregivers.” How to access: https://www.cutitforward.org/ |

| Think of US | Background: “Think of Us (TOU) is a research and design lab on a mission to fundamentally re-architect the foster care system as we know it, powered by the data, leadership and insights of people with lived experience.” How to access: https://www.thinkofus.org/who-we-are/about-us |

| Children’s Rights | Background: “Through relentless strategic advocacy and legal action, we hold governments accountable for keeping kids safe and healthy.” How to access: https://www.childrensrights.org/ |

| Annie E. Casey Foundation | Background: “The Annie E. Casey Foundation is developing a brighter future for children and youth at risk of poor educational, economic, social and health outcomes.” How to access: https://www.aecf.org/ |

| First Focus on Children | Background: “First Focus on Children is a bipartisan advocacy organization dedicated to making children and families the priority in federal policy and budget decisions.” How to access: https://firstfocus.org/ |

| Children’s Defense Fund | Background: “The Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit child advocacy organization that has worked relentlessly for more than 40 years to ensure a level playing field for all children.” How to access: https://www.childrensdefense.org/about/who-we-are/our-mission/ |

| Child Welfare League of America | Background: “CWLA is a powerful coalition of hundreds of private and public agencies that since 1920 has worked to serve children and families who are vulnerable.” How to access: https://www.cwla.org/about-us/ |

| Generations United | Background: “The mission of Generations United is to improve the lives of children, youth, and older people through intergenerational collaboration, public policies, and programs for the enduring benefit of all.” How to access: https://www.gu.org/who-we-are/mission/ |

| National Foster Youth Institute | Background: “The National Foster Youth Institute is a youth development organization that lifts up foster youth voices to transform the child welfare system.” How to access: https://nfyi.org/ |

| Foster Care Alumni of America | Background: “FCAA connects the alumni community to transform policy and practice, ensuring opportunity for people in and from foster care.” How to access: https://fostercarealumni.org/ |

| National Association of Counsel for Children: NACC | Background: “NACC trains and certifies attorneys who represent children, families, and agencies; supports a diverse community of professionals; and advocates for policy reform alongside young people and families.” How to access: https://naccchildlaw.org/ |

Federal and State Policy Recommendations

Policy is the blueprint for change. The child welfare legislative history has demonstrated policy that does not center Black lives. There is a need for policy that centers prevention methods and aims to decrease the policing of Black families. Child welfare laws must start to center Black voices and value Black lives. The child welfare system and policies can no longer operate from a perspective that sees Black people as disadvantaged but instead from a lens that sees Black people as targets of oppression. The child welfare industry must address the harm child welfare policies have inflicted on the Black community.

To help protect Black families and Black youth impacted by the child welfare system:

- Congress and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services should require states receiving federal Title IV-B and Title IV-E funding to report the number of placements a child experiences during their time in foster youth care. States should report the number of placements experienced to federal reporting systems such as AFCARS and the National Youth Transition Databases. The number of placements that a child is moved to while experiencing the child welfare system can be a risk factor for poor outcomes. Understanding the number of placements, a youth has experienced can serve as a prevention tool and help industry professionals improve services.

Federal and state policymakers and administrators should use a culturally appropriate and intersectional lens when regulating policies, allocating funds, and creating policies impacting Black families. Additionally, states should take steps to reevaluate and revise their definition of neglect so that families aren’t penalized for being poor.

Conclusion

The lives of Black foster youth matter. The one size fits all approach to serving youth in foster care is not effective in serving Black foster youth. To offer effective support to Black youth and families impacted by the child welfare system, its essential to understand the history of how Black families and children have been dehumanized and undervalued by the United States Child Welfare System. This resource guide serves as a tool to provide industry professionals, policymakers, community members, and families with insight on how to serve Black youth in foster care best. Endn

[i] Children’s Bureau. (n.d.). Working With Black Families. Child Welfare Information Gateway; Children’s Bureau Child Welfare Information Gateway. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/systemwide/diverse-populations/

[ii] Id.

[iii] Children’s Bureau. (n.d.). About AFCARS. About AFCARS Fact Sheet; Administration for Children and Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/fact-sheet/about-afcars

[iv] Children’s Bureau. (2022). The AFCARS Report No. 29 (No. 29; Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau.

[v] Id.

[vi] United States Census Bureau. (n.d.). United States Census Bureau QuickFacts. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/IPE120221

[vii] Children’s Bureau. (2020). Fact Sheet: How the Child Welfare System Works. Child Welfare Information Gateway.

[viii] National Center for Child Welfare Excellence. (n.d.). What is Youth Permanency? Retrieved from National Center for Child Welfare Excellence at the Silberman School of Social Work: http://www.nccwe.org/toolkits/youth-permanency/what_is_youth_permanency.html.

[ix] Supra Note 8.

[x] Id.

[xi] Id.

[xii] The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2019, June 6). What is Foster Care? Retrieved from The Annie E. Casey Foundation: https://www.aecf.org/blog/what-is-foster-care/

[xiii] JBS International Inc. (n.d.). Types of Maltreatment. Retrieved from Child and Family Services Reviews Information Portal: https://training.cfsrportal.acf.hhs.gov/section-2-understanding-child-welfare-system/2979

[xiv] Supra Note 2.

[xv] Id.

[xvi] Shared Justice Initiative of the Center for Public Justice. (2017, March 30). Aging Out of Foster Care: 18 and On Your Own. Retrieved from Shared Justice: http://www.sharedjustice.org/most-recent/2017/3/30/aging-out-of-foster-care-18-and-on-your-own

[xvii] Children’s Home Society and Lutheran Social Service of Minnesota. (2019, January 2019). Infographic- What Happens When Kids Age Out of Foster Care?. Retrieved from Children’s Home Society and Lutheran Social Service of Minnesota: https://chlss.org/blog/infographic-what-happens-when-kids-age-out-of-foster-care/

[xviii] Id.

[xix] Gordon, L. (2011). Child Welfare: A Brief History. Social Welfare History Project; VCU Social Welfare History Project. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/programs/child-welfarechild-labor/child-welfare-overview/

[xx] Supra Note 21.

[xxi] Id

[xxii] Id

[xxiii] Id

[xxiv] Id

[xxv] Lawrence-Webb, C. (1997). African American Children in the Modern Child Welfare System: A Legacy of the Flemming Rule. Child Welfare, 76(1), 9–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45399315

[xxvi] O’Neill Murray, Kasia , & Gesiriech, S. (n.d.). A Brief Legislative History of the Child Welfare System. Massachusetts Legal Assistance Corporation. https://www.masslegalservices.org/system/files/library/Brief%20Legislative%20History%20of%20Child%20Welfare%20System.pdf

[xxvii] Supra Note 25.

[xxviii] Alliance for Children’s Rights. (2021). The Path to Racial Equity in Child Welfare: Valuing Family and Community (2021 Policy Summit Report). https://allianceforchildrensrights.org/wp-content/uploads/REJPS_summit_report.pdf

[xxix] Supra Note 26.

[xxx] Id.

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] Id.

[xxxiii] Id.

[xxxiv] Supra Note 28.

[xxxv] Supra Note 26.

[xxxvi] Id.

[xxxvii] Id.

[xxxviii] Supra Note 28.

[xxxix] Id.

[xl] Supra Note 26.

[xli] Supra Note 28.

[xlii] Id.

[xliii] White, S., & Persson, S. (2002, October 13). Racial Discrimination in Child Welfare Is a Human Rights Violation—Let’s Talk About It That Way. American Bar Association; American Bar Association. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/litigation/committees/childrens-rights/articles/2022/fall2022-racial-discrimination-in-child-welfare-is-a-human-rights-violation/

[xliv] Id.

[xlv] Id.

[xlvi] Supra Note 28.

[xlvii] Supra Note 43.

[xlviii] Id.

[xlix] Wulczyn, F. (2002). Adoption Dynamics: The Impact of the Adoption and Safe Families Act. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/adoption-dynamics-impact-adoption-safe-families-act-asfa

[l] Id.

[li] Id.

[lii] Supra Note 43.

[liii] Id.

[liv] Id.

[lv] Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. (2020). The Multiethnic Placement Act 25 Years Later. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation

[lvi] Partners For Our Children. (2021). The Multi-Ethnic Placement Act and Interethnic Adoption Provisions (MEPA-IEP): A Failed Policy Filled with Unintended. Alexandria: Partners for our Children.

[lvii] Florida’s Center for Child Welfare. (n.d.). MEPA/ IEPA Overview. Tampa: Florida’s Center for Child Welfare.

[lviii] National Association of Black Social Workers. (2021). The National Association of Black Social Workers (NABSW) Calls for the Repeal of the Multi-Ethnic Placement Act (MEPA) and Inter-Ethnic Placement Act (IEPA). The Guardian, 43(04).

[lix] Supra Note 55.

[lx] Id.

[lxi] Children’s Rights. (2023). Racism At the Front End of Child Welfare: Fact Sheet. Children’s Rights. https://www.childrensrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/CR-Racism-at-the-Front-End-of-Child-Welfare-2023-Fact-Sheet.pdf

[lxii] Id.

[lxiii] Id.

[lxiv] Id.

[lxv] Supra Note 43.

[lxvi] Supra Note 61.

[lxvii] Id.

[lxviii] Perez, J. (2023, February 24). The foster care-to-prison pipeline: A road to incarceration. The Criminal Law Practitioner. https://www.crimlawpractitioner.org/post/the-foster-care-to-prison-pipeline-a-road-to-incarceration

[lxix] Supra Note 43.

[lxx] Id.

[lxxi] The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2023, May). Child Welfare and Foster Care Statistics. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://www.aecf.org/blog/child-welfare-and-foster-care-statistics

[lxxii] Id

[lxxiii] Epstein, R., Blake, J., & Gonzalez, T. (2017). Girlhood interrupted: The erasure of black girls’ childhood. Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/poverty-inequality-center/wpcontent/uploads/sites/14/2017/08/girlhood-interrupted.pdf

[lxxiv] Id.

[lxxv] Id.

[lxxvi] Patrick, K., & Chaudhry, N. (2017). Let her learn: Stopping school pushout for girls in foster care. National Women’s Law Center. https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/final_nwlc_Gates_GirlsofColor.pdf

[lxxvii] Id.

[lxxviii] Id.

[lxxix] Supra Note 33.

[lxxx] Davey, S. (2020, May). Snapshot on the State of Black Women and Girls: Sex Trafficking in the U.S. Retrieved from CBCFINC.org: https://www.cbcfinc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/SexTraffickingReport3.pdf

[lxxxi] Id.

[lxxxii] Right4Girls. (2018). Domestic Child Sex Trafficking and Black Girls. Retrieved from Right4Girl.org: https://rights4girls.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/JJ-DCST-UPDATED-SEPT-2020_Final-1-1-1.pdf

[lxxxiii] Id.

[lxxxiv] Id.

[lxxxv] Supra Note 33.

[lxxxvi] Supra Note 36.

[lxxxvii] Id.

[lxxxviii] https://theinstitute.umaryland.edu/media/ssw/institute/Cuyahoga-Youth-Count.6.8.1.pdf

[lxxxix] Id

[xc] Jackson, M. (2012). Cultural Broker Family Advocate Program. California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare. https://www.cebc4cw.org/program/cultural-broker-program/detailed