By Tatyana Hopkins, John R. Lewis Social Justice Fellow

Introduction[1]

“As cannabis goes mainstream, it’s easy to forget the past.” – Fred “Fab 5 Freddy” Brathwaite, Hip hop pioneer and director of Netflix’s Grass is Greener, 2019

Despite an increasing number of states across the United States moving to legalize the medical and recreational use of cannabis, the federal government has held to its century-long position that cannabis is an illegal drug with no recognized safe use. But even in the face of federal prohibition, the cannabis market continues to explode. In 2022, the legal U.S. cannabis market was worth an estimated $29 billion across state medical and recreational sales.[i] And even further, industry research analysis projects that the likelihood for several new cannabis legalization efforts can drive the U.S. legal cannabis market to become a $72 billion industry by 2030.[ii]

According to the analysis, even if its estimated 18 new state markets do not enact legalization measures, existing legal markets, alone, have the potential to reach $57 billion by 2030. As one of few industries to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic stronger, the market’s growth rate makes cannabis one of the fastest growing industries in the nation.[iii] However, not everyone will have an equal chance to participate in this historic economic opportunity.

Although more than half of the American population are people of color, most cannabis businesses are majority-owned and operated by white people.[iv] A 2017 survey found that 81% of cannabis business owners in the U.S. were white, 5.7% identified as Hispanic, and 4.3% identified as Black.[v] However, a more recent 2021 analysis reported that Black people only represent 1.2% to 1.7% of cannabis business owners.[vi] But the racial disparities in the cannabis industry go beyond just a lack of representation in minority business ownership and extend to a long history of minority overrepresentation in punishment for cannabis-related crimes.[vii] This is in part due to the “War on Drugs,” where Black individuals were singled out and charged with more serious or lengthy sentences for the same drug offenses when compared to white offenders.[viii] Many states have implemented “social equity” programs to help communities most impacted by the War on Drugs obtain licensing in their legal cannabis markets.[2] But these programs are failing to create a diverse and inclusive cannabis industry.[ix]

As the central reigning governmental body of the 50 states and territories, the federal government is uniquely poised to address such issues of social equity and justice in the cannabis community, and as a driving force of the racialized War on Drugs, it is uniquely obligated to help address such issues. With the legal cannabis market in the U.S. slated to become a $72 billion market by 2030 across the legal states, the federal government must emphasize, model, and encourage states, to engage in effective social equity programming. It must also approach prospective federal cannabis-focused policy through the lens of social equity.

A Budding Industry

“Make the most you can of the Indian Hemp seed and sow it everywhere.” – President George Washington, 1794

Cannabis Legalization Across the States

| Medical | Recreational | No Medical or Recreational Use |

| Alabama Arkansas Delaware Florida Hawaii Illinois Louisiana New Hampshire North Dakota Ohio Oklahoma Pennsylvania South Dakota Utah West Virginia | Alaska Arizona California ColoradoConnecticut District of Columbia Maine Maryland Massachusetts Michigan Minnesota Mississippi Missouri Montana Nevada New Jersey New Mexico New York Oregon Rhode Island Vermont Virginia Washington | Georgia Idaho Indiana Iowa Kansas Kentucky Nebraska North Carolina South Carolina Tennessee Texas Wisconsin Wyoming |

The projected growth of the cannabis industry in the coming years will not be the plant’s first big economic boom. Hemp, a type of cannabis known for its industrial uses, was such an essential crop to the establishment of the U.S. that farmers could be fined, and even jailed, for not growing it.[x] A 1619 decree by King James I required Virginia colonists to grow hemp, and by the mid-1700s, mandatory cultivation was imposed in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and the middle colonies.[xi] A primary crop of President George Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation, hemp remained a critical economic resource in post-colonial America through the 18th and 19th centuries until its domestic production declined after the Civil War.[xii] Then, a crusade for its prohibition in the early 20th century made the plant illegal, federally and in most states.

A decade ago, no state had legalized cannabis for recreational use. This was until late 2012, when Colorado and Washington authorized their adult use programs. Today, public attitudes have shifted dramatically. Since then, support in favor of cannabis legalization has grown from about half to two-thirds of Americans.[xiii] And now, most states have laws to permit cannabis use under certain circumstances. In October 2022, President Joe Biden directed the Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. attorney general to expedite a medical and scientific re-examination of the Schedule I classification of cannabis. Although cannabis remains federally illegal, medical cannabis is currently legal in 37 states, three territories, and the District of Columbia. Additionally, the recreational use of cannabis has been legalized in 21 states, two territories, and D.C.

The industry centers on the production and sale of medical and recreational cannabis products such as cannabis flowers, edibles, concentrates, oils, and tinctures. Licensing, tax, and regulatory requirements vary by state. But businesses typically fall into one of several categories:

- Retail: Dispensaries and other shops sell finished cannabis products directly to consumers.

- Cultivation: Using a variety of techniques—such as hydroponics, aeroponics, and cloning—cultivators grow, harvest, and process cannabis products for sale.

- Manufacturing: Laboratories and kitchens make, package, and properly label a wide range of cannabis products. This includes edibles, tinctures, salves, concentrated wax and oil extracts, and other products.

- Distribution: Under strict regulations, distributors transport cannabis products from cultivators and manufacturers to dispensaries, smoke shops, and other retailers.

- Ancillary Businesses/Service Operations: A host of “non-plant-touching” businesses provide services related to the cannabis industry. This includes software, advertising, packaging suppliers, and cannabis real estate and regulatory compliance expertise.

The industry’s estimated growth reflects a new wave of job creation and fresh business opportunities. But social equity will be critical to ensuring that communities that bore the brunt of racist drug policy and enforcement can capitalize on the industry’s transition from illicit to emerging market.

The Racialized Prohibition of Cannabis

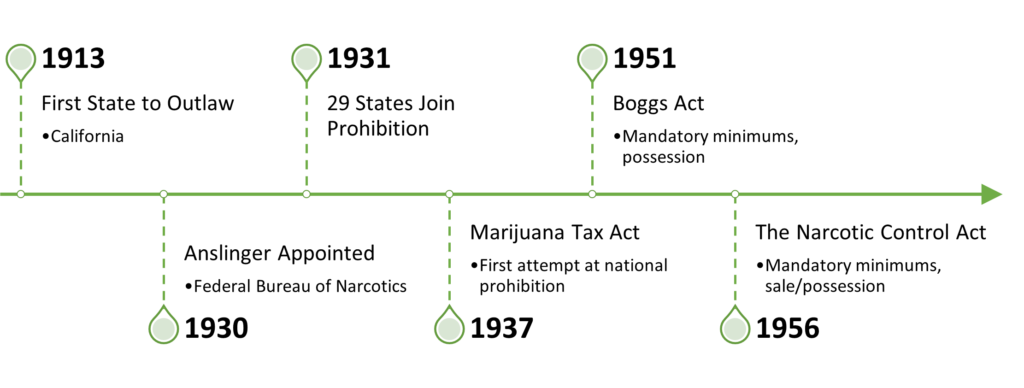

Cannabis Prohibition Measures

“There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz and swing, results from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers, and others.” – Harry J. Anslinger, Commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics

A long history of racially targeted law enforcement and mass incarceration underscore the need for social equity in the cannabis industry.

Over a century ago, California became the first state to outlaw cannabis in 1913, and its motivations were expressly racist.[xiv] On the national level, Harry J. Anslinger pushed for the federal prohibition of cannabis. Appointed as the first head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) in 1930—just three years before alcohol prohibition failed—Anslinger was one of the first architects of the War on Drugs.

Despite previously taking the stance that it was an “absurd fallacy” that cannabis made people violent or mentally ill, while at the FBN he waged a relentless war against cannabis.[xv] Armed with scant scientific evidence and racial prejudice against non-white groups, for 32 years Anslinger worked to shift the cultural mindset toward the idea that cannabis was dangerous.[3] He played on racist and xenophobic sentiments to win public favor.[4] Anslinger claimed that Black people and Hispanics were the primary users of cannabis, and its intoxicating effects made them forget their place in the fabric of American society and led them to create social chaos.[xvi] He, and other propogandists, even changed the word itself, from cannabis to marijuana, a Spanish word, so that it would more likely be associated with Mexicans.[xvii]

The spread of alarming myths about the propensity of cannabis to provoke madness, violence, and death grew in the early 20th century, and by 1931—a year into Anslinger’s term—29 states outlawed cannabis.[xviii] The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 (MTA) was the first attempt at national cannabis prohibition. Designed to heavily regulate the drug’s sale and distribution, it criminalized cannabis and restricted its possession to individuals who paid an excise tax for certain medical and industrial uses.

A 1944 investigation, commissioned by New York City Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and compiled by researchers from the New York Academy of Medicine, largely refuted the propogandist claims that cannabis caused feral madness among its users. Known as the LaGuardia Report, it concluded that cannabis had relatively mild effects, especially compared to alcohol and opium, and did not lead users to psychosis or make them prone to crime.

Despite contradictions to racialized prohibitionist propaganda—which ignored rational assessments of the actual risks of cannabis—the period of racialized prohibition lasted for decades and resulted in the overwhelming criminalization of minority groups.[xix]

Even today, despite legalization, racial disparities continue. In some states, racial disparities in cannabis arrests were larger in 2018 than in 2010, when only two states adopted recreational use.[xx] Overall, Black people are 3.64 times more likely than white people to be arrested for cannabis offenses despite similar usage rates.[xxi]

The War on Drugs and its Criminalization of Black Communities

Fueling Mass Incarceration

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies—the anti-war left and Black people. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black. But by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalize both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, and vilify them night after night on the evening news.” – John Ehrlichman, Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs under President Nixon, 1994

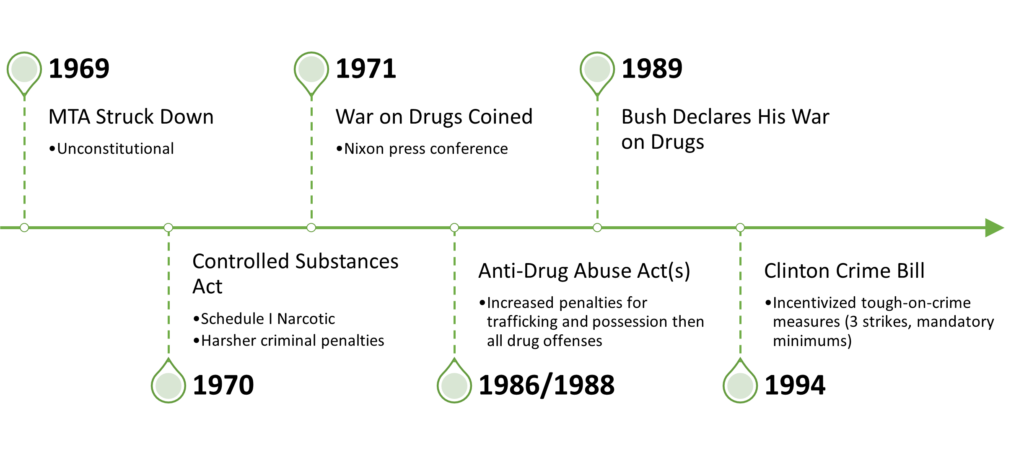

The legacy of the racialized prohibition of cannabis in the early 20th century and President Richard Nixon’s War on Drugs in the latter half of the century run parallel.

In 1971, Nixon launched his War on Drugs, a national campaign to increase support to federal drug control agencies to reduce the use, possession, and sale of illegal drugs. Its efforts imposed stiffer criminal and civil punishments for drug offenses. The Nixon Administration’s first attack on drug trafficking was its authorization of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Controlled Substance Act of 1970 (CSA). An extension of the MTA of 1937 (held unconstitutional in 1969), the CSA provided the framework for listing cannabis as a Schedule I drug. The law, which marked cannabis as a substance with no medical value and a high potential for abuse, was the product of a commission to establish the dangers of cannabis. However, it was later revealed that the commission, led by former Pennsylvania Governor Raymond Shafer, worked to target Black people and the antiwar movement instead of engaging in a legitimate scientific inquiry about cannabis.[xxii]

Today, the War on Drugs is criticized for its role in the excessive criminalization and racial profiling of communities of color, particularly Black communities. At the height of the drug war, a Black man was 11 times more likely to be arrested than a white man.[xxiii] Now, Black and Latino people make up more than half of all Americans who have been to prison.[xxiv] More likely to receive harsher sentence, they also account for nearly 80% of people in federal prison and almost 60% of those incarcerated in state prison on drug-related offenses.[xxv] Black men alone make up 35% of the U.S. prison population.[xxvi]

The War on Drugs is also criticized for its failure to thwart the demand for drugs and its role in creating a public health crisis due to its diversion of social support and harm reduction resources to law enforcement. Congress has allocated increasingly large amounts of money to agencies and programs related to drug control. Annually, it spends $51 billion on drug policy enforcement. It is estimated that Congress has cumulatively spent $1 trillion on the War on Drugs.[xxvii] Since its inception, the national prison population has skyrocketed to unprecedented rates. From 1980 to 1997, the number of Americans incarcerated for nonviolent drug offenses soared from 50,000 to over 400,000.[xxviii] America is now the world’s most incarcerated country per capita.[xxix] Although the U.S. represents less than 5% of the international population, its jails and prisons account for nearly 16% of the global incarcerated population.[xxx] Currently, drug offenses are the country’s leading cause of arrest, with more than a million Americans arrested for simple drug possession each year.[xxxi]

For those millions of Americans arrested and incarcerated for drug-related offenses, punishment is far reaching, and disproportionately so for people of color. The consequences for such offenses extend beyond incarceration to a range of matters such as employment, voting rights, public housing and other public assistance programs like food stamps, child custody, student aid, immigration status, driver’s licensing, and business loans.

Advancing Social Equity and Justice Through the Federal Government

“Segregation forced interdependence. Today that entrepreneurial spirit can only be recaptured with the support of the established business community, by prodding of government, and from Black folks helping black folks. The only Black business that can make it without such accords is a funeral home. To go it alone, blacks have to die.”- Don Ross, The Oklahoma Eagle, 1994

The enforcement of low-level, nonviolent drug policy has fueled mass incarceration and widened the national racial economic divide, making it difficult for minorities to participate in the cannabis industry. Just 2.7% of cannabis entrepreneurs with a plant-touching business are Black and 5.3% are Latinos and only 5.6% of cannabis ancillary businessowners are Black, while 6% are Latino.[xxxii] In sharp contrast, 81.3% and 80% of plant-touching and ancillary businessowners, respectively, are white.[xxxiii]

Economic disparities directly flow from racial injustices in the nation’s criminal legal system.[xxxiv] Today, the net worth of white households is 10 times higher than Black households—only a slight improvement in the five decades since the Civil Rights Movement.[xxxv] A Brennan Center for Justice analysis of the long-term economic effects of encounters with the criminal legal system found that Black and Latino people suffer greater lifetime earning losses due to system involvement than white people.[xxxvi] According to the report, formerly incarcerated Black and Latino people lose $358,900 and $511,500, respectively, in lifetime earnings, while their white counterparts lose about $267,000. Concluding that the prison system has had profound impacts on Black and Latino wealth, it explained that Black and Latino people’s overrepresentation in the criminal system concentrated the economic impacts of system involvement within those communities and exacerbated the racial wealth gap.

The cost of doing business in the cannabis industry are higher than other startups, so much so that it can be prohibitive for those disproportionately penalized for cannabis-related crimes trying to capitalize on the legal cannabis market. According to Forbes, while its costs $50,000-$150,000 to open a regular retail clothing shop, it costs at least $250,000 to open a retail cannabis operation.[xxxvii] Nonrefundable application fees can cost up to $200,000. Additionally, potential licensees may be required to show proof of assets upwards of $2 million, with the state-imposed capital requirements requiring a portion of assets to be held in cash amounts ranging from $150,000-$250,000. Then, the complicated legal nature of federal and state cannabis regulations drives up costs for financial services, inventory packaging, specialized point-of-sale software to integrate with government systems, and other day-to-day operation services. Initial security equipment can cost $65,000, while legal services, alone, can cost as much as $50,000 a year.

To address the lack of diversity in the cannabis industry, some states have enacted social equity programs that aim to promote equity and inclusion by providing resources, mentorship opportunities, and incentives for diverse ownership. The goal is to ensure that communities unduly harmed by discriminatory drug enforcement are included in the new and growing legal cannabis industry. In 2018, Massachusetts became the first state to create and implement a state social equity program whose regulations provide for resources, training, and education to minority and other marginalized communities. However, efforts to help communities of color succeed in the cannabis industry have not created a diverse cannabis market anywhere.[xxxviii]

Having played a major role in starting and funding the War on Drugs, that heavily criminalized nonviolent drug offenses for decades, the federal government has a unique responsibility to rectify the harms of the drug war. This includes developing reforms that shape the cannabis sector into a just and equitable industry, especially as President Biden calls on his administration to rethink the federal government’s position on cannabis scheduling. While the federal government has taken a largely hands-off approach on state-legal cannabis activity, the federal prohibition continues to create complex legal barriers that make it harder for minority operators, who often struggle to access capital, to enter the industry.

While federal legalization would be a huge step towards equity, it is unlikely.[xxxix] But even in the face of its own prohibition, the federal government can still make positive contributions to social equity in cannabis, and it is uniquely positioned to nudge states towards equity through Congress’ robust spending power.

The subsequent section identifies specific areas where federal action is necessary to further social equity.

1. Federal Model

The primary barriers affecting minority operators are that licenses are expensive and difficult to get; complicated applications; federal policies making it nearly impossible to obtain bank loans; limited access to private investors and low-interest loans; and maintaining compliance.[xl]

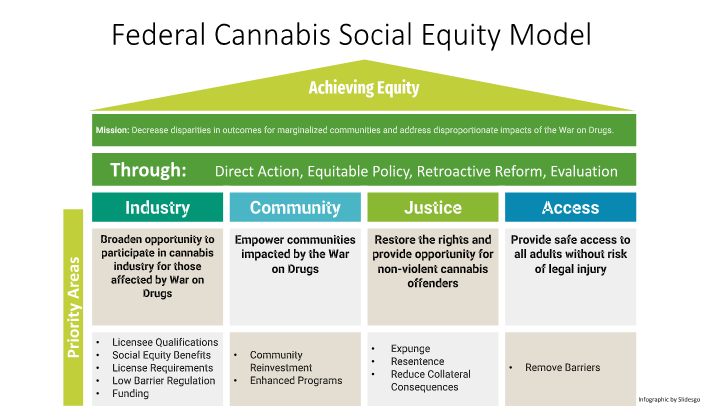

While some legal states have opted to enact social equity initiatives, the state-level approach means the aims, resources, and regulations of social equity vary greatly by state.[xli] The federal government should develop a comprehensive social equity model that drive national cannabis-related policy and sets standards for the national cannabis industry.

Critique of Federal Model Policy Options

Calls for social equity in the cannabis industry have grown increasingly louder in recent years, but only about a third of legal states have such program. Out of the 19 states with adult-use cannabis, 13 have developed social equity programs to help marginalized people enter their legal cannabis markets. States with social equity programs include Arizona, California, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Vermont, and Virginia. Colorado and Washington are in the process of implementing social equity programs. However, executing social equity has proven to be challenging, with diverse ownership and employment lagging even in the most regulated markets.

Although social equity programs vary greatly by state, the 2022 Minority Cannabis Business Association (MCBA) Social Equity report—one of the most comprehensive reviews of social equity programs nationwide—identified major flaws in existing social equity programs across the country.[xlii] It found that despite broad calls for social equity, certain barriers prevented minority operators from advancing in the industry:

- Despite cannabis prohibition having race-based harms, there is a lack of race-based criteria in social equity qualifications and definitions. Only Arizona, California, and Michigan use remedial race classifications. Some others make ethnic minorities eligible for fee waivers and other resources. Most others use alternative for race such as income, criminal conviction, and residency in a qualified neighborhood.

- Twenty-six states impose license caps that arbitrarily inflate the value of licenses in the state, due to lack of competition, and give little incentive for the legacy market to transition to the regulated market. Limited licenses often result in lawsuits by large operators, which can be an obstacle for minority operates.

- Too few programs provide funding for social equity applicants and licensees. Despite income the persistence of racial wealth inequity, only six programs (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, New York, and Virginia) provide funding for applicants beyond fee waivers or reductions. Lack of timely funding can leave applicant vulnerable to partners who deprive the social equity operator of meaningful ownership.

- Requirements to secure premises prior to issuance of a license or conditional license can be a barrier for social equity applicants given the high cost of commercial real estate and premium on properties in areas zoned for cannabis businesses. Twenty-three programs (11 adult use, 12 medical) require applicants to secure a building prior to obtaining a license.

- Out of 36 medical programs, 34 exclude those with felony convictions for participating. Similarly, 14 of 18 adult use programs explicitly disqualify applicants for certain felony convictions. New Jersey, Alaska, Oregon, Montana, and Maine bar applicants due to previous cannabis convictions. The remaining nine states exempt individuals with qualifying cannabis offenses from their bans.

Social equity programs must continue to prioritize and expand current to support minority applicants and licensees.

Federal Model Policy Recommendations

By outlining the parameters of social equity, the federal government will bring the national cannabis industry closer to ensuring stakeholders have equitable opportunities to participate:

- Adopt a Social Equity Model. Federal standards guide a range of businesses and industries, including labor and safety regulations, environmental standards, and other requirements. Such standards protect the rights of all stakeholders, encourage fairness, and ensure uniformity across jurisdictions. A comprehensive federal social equity model to guide new and veteran legal states in reducing racial disparities in their cannabis markets is an important step toward economic and social justice in the industry. The model should identify priority policy areas as well as way to approach meeting the model’s goals.[xliii]

- Pass the MORE Act. Reintroduced by Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY), the Marijuana Opportunity, Reinvestment, and Expungement (MORE) Act would end federal prohibition. The House previously passed the act in 2020, but it did not advance in the Senate. The bill would also eliminate related criminal penalties and take steps towards social and criminal justice as well as advance economic development. Under MORE Act, federal cannabis-related record would be automatically expunged. Further, a 5% tax on the retail sales of cannabis products would go into an Opportunity Trust Fund. It would also create the Office of Cannabis Justice to oversee federal social equity provisions.

- Provide funding. Economic and wealth disparities are among the many collateral consequences of the War on Drugs. Despite this, only six of 18 state social equity programs provide funding for social equity applicants and operators beyond fee reductions and waivers.

- Promote equitable licensing schemes. Requirements to secure a premises prior to issuance of a license is a barrier for social equity operators, especially considering the high cost of “green zone” properties. Schemes that require applicants to acquire property or hold large amounts of liquid cash are also generally inaccessible to minority entrepreneurs.

- Embrace the legacy market. The federal government should incentive states to create pathways from the legacy market to the legal market. Often marked by a criminal history, the legacy market is comprised of those who participated in cannabis before it became a legal industry. The federal government should open the market for those even with a prior conviction.

2. Banking

Under current federal law, any deposit of cannabis proceeds, legal or otherwise, to a financial institution, can be deemed as money laundering because of cannabis’ federal classification as a Schedule I drug. Forced to operate without bank accounts, checks, credit cards, loans, or lines of credit, businesses in the nearly $30 billion cannabis industry, operate largely in cash. However, this cash-only model can be a serious liability, and restricted access to business loans makes business unsustainable for minority operators.[xliv]

Through the third quarter of 2022, only 489 banks and 166 credit unions nationwide provided banking services to cannabis businesses.[xlv] That is because federal laws such as the Controlled Substances Act, the Bank Secrecy Act, and anti-money laundering laws subject financial institutions that provide financial services to the cannabis industry to severe legal and regulatory consequences. This is true even if the serviced cannabis business operates legally under state law for medical or adult recreational use. Struggling to obtain and maintain financial services, upwards of 70% of cannabis business operate wholly in cash—which carries financial and safety liabilities that cause additional overhead expenses.[xlvi]

Storing cash onsite increases the risk of robbery and employee theft for cannabis businesses. In fact, about 90% of all loss in the industry is attributed to employee theft.[xlvii] As a safeguard, many states have imposed stringent security requirements on cannabis businesses. The additional labor and other costs associated to meet compliance with security regulations also increase the general expenses of cannabis businesses. Cash operation also creates complications to typical operational tasks such as managing payroll, as it can make it more difficult to document wages paid for taxation purposes, and therefore, increase the likelihood of Internal Revenue Service (IRS) audits. Further, operating without relationships with financial services makes it impossible for cannabis businesses to accept check and credit card payments. And these challenges are only amplified for Black and minority cannabis business owners.[xlviii]

The SAFE Banking Act

To help cannabis businesses cope with the financial obstacles imposed by federal banking regulations, federal lawmakers introduced legislation that would allow legal cannabis businesses to bank without the fear of prosecution. The Secure and Fair Enforcement (SAFE) Banking Act was first introduced in the U.S. House in 2019. The bill’s aim was to provide banks and credit unions with a legal avenue to do business with cannabis businesses operating legally under state law. Under the law, banks and credit unions could avoid persecution and penalties from federal regulators for providing loans and other financial services to legitimate cannabis businesses. The bill also required federal banking regulators to provide guidance on how to safely provide financial services to cannabis businesses.

The bill aimed to establish a framework for financial institutions to provide services to cannabis businesses with assurance that they could remain compliant with both state and federal laws. The central provision of the Safe Banking Act prohibited federal banking regulators from penalizing deposit institutions for providing financial services to legitimate cannabis businesses. For example, the bill would have prevented termination and limitation of deposit insurance solely because a bank or credit union offered services to a cannabis business. It would also have prevented federal regulators from ordering a depository institution to terminate a customer account unless it had a valid reason for doing so that was not solely based on its status as a cannabis business.

Additionally, the bill would have required banks, credit unions, and other financial institutions to adhere to certain guidelines when engaging with cannabis businesses. Under the act, financial institutions would have to limit the type and number of accounts offered to cannabis businesses as well as impose additional due diligence requirements for such account holders. It further required financial institutions to report suspicious activity to the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network for purposes of anti-money-laundering compliance. Cannabis businesses would also have to send monthly reports to maintain eligibility for banking services.

However, the SAFE Banking Act failed, for the third time, to pass the Senate in its most recent December 2022 vote as part of a larger budget package—leaving cash management up in the air for cannabis businesses and keeping small cannabis operators without support from financial institutions.

Making SAFE Banking Better

Entrepreneurship is often viewed as a tool for alleviating racial disparities in economic mobility, wealth accumulation, and job creation in minority communities, and access to financial capital is a critical element of new business formation.[xlix] While Black businesses have traditionally faced difficulties getting bank loans, the complicated legal nature of financial regulation in the cannabis industry has only deepened their lack of access to capital. Sponsors of the SAFE Banking Act claimed that it would also help address small and minority-owned cannabis businesses access needed banking services and loans. However, critics of the SAFE Banking Act called out its lack of social equity measures that would result in equitable access to financial services.[l] The most recent version of the bill did not include any language about racial equity that would ensure that it would help minority cannabis business owners or those affected by discriminatory drug law enforcement.

Low-income, Black and Hispanic, and formerly incarcerated entrepreneurs have been historically disadvantaged by cannabis prohibition laws and face a great deal more barriers to participating in the economic opportunities of the burgeoning legal cannabis market.[li] Cannabis businesses are uniquely expensive and difficult to operate, and experts are often necessary to navigate the abundant and strict regime of state and federal regulations.[lii] While large firms with angel investors and venture capitalist can use private funds to build cannabis empires, people of color and small operators must often rely on themselves. Minority entrepreneurs generally lack financial backing, and the federal regulations on banking and taxation make bank loans and tax cuts unavailable to them.

Banking discrimination has long been a challenge facing Black-owned businesses in the United States. Despite various federal legislative measures to reduce financial discrimination taken, little progress has been made in mitigating the financial system’s decades-long practice of discriminating against Black business loan seekers.[liii] Banks still tend to prefer providing services to white customers and provide them with cheaper interest rates than African American loan seekers.[liv] A 2023 Intuit QuickBooks survey showed that 57% of Black business owners were denied a bank loan at least once when starting their businesses, compared to 37% of non-Black business owners.[lv]

Banking Policy Recommendations

The SAFE Banking Act has the potential to address issues of social equity in cannabis banking and lending. By clarifying the legal landscape for providing financial services to cannabis businesses and creating a more secure banking environment, the bill may increase minority operators’ access to needed financial resources.

However, its most recent introduction was absent of any language to ensure that Black and minority businesses would be adequately served and protected by the law. In addition to passing the SAFE Banking Act, federal legislators must clarify the bill’s social equity aims and amend its language to include anti-discrimination provisions:

- Require Federal Anti-Discriminatory Compliance. The SAFE Banking Act should be amended to require financial institutions to demonstrate compliance with federal anti-discrimination laws as a condition of safe harbor.

- Protect Minority Depository Institutions. The SAFE Banking Act should be amended to explicitly protect Minority Depository Institutions and Community Development Financial Institutions.

- Require State and Local Compliance. Amendments to the SAFE Banking Act should promote compliance with state and local regulatory requirements regarding business ownership and other social equity measures.

- Update the Community Reinvestment Act. The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) was enacted in 1977 and has largely gone unchanged since 1995. The law required the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Federal Reserve, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) to assess how financial institutions meet the needs of the communities they serve, including poor ones. While the OCC sought to modernize the CRA, it later moved in favor of an interagency approach, the efforts of which were criticized for making it too easy for banks to pass CRA evaluations.[lvi]

- Despite the legislation, there are wide disparities in access to credit for Black communities at the local level, including higher interest rates on business loans and lower bank branch density.[lvii] The current CRA framework restricts geographic footprint of CRA activities to areas around physical locations. The CRA evaluation standards are vague and can be subject to examiner discretion across the agencies, which can create confusion about how banks should serve low-income areas. Agencies should update the definition of an assessment area, clarify the kinds of investments banks are permitted to make, and revise the regulatory framework to establish an evaluation method for banks without physical locations.[lviii] CRA evaluations can also take years to complete. This means that upon release, the reports do not reflect the communities banks currently serve or any progress made since the evaluation. Updates to the CRA evaluation process should require examiners to issue final evaluations in a timely and defined period.

- Pass the CLAIM Act. In addition to complicating banking, the division between federal and state law regarding the legal status of cannabis has also made it more difficult for cannabis businesses to receive comprehensive and affordable insurance policies. The Clarifying Law Around Insurance of Marijuana (CLAIM) Act was introduced in the Senate in March 2021, where it awaits further action. The bill would allow insurer to provide coverage to cannabis businesses without the threat of federal prosecution.

- According to a 2021 report by New Dawn Risk, only about 30 U.S. insurers offer cannabis businesses insurance.[lix] According to the report, such insurance products are not formally advertised and required to operators to pay their premiums in cash to obtain coverage, which is a “unique obstacle that most other businesses do not face.”[lx] Further, current providers currently offer inadequate policy limits on coverage. While operators may need limits between $5-10 million, insurers generally only offer $1 million per occurrence/$2 million aggregate policies in commercial and general liability, property damage, and product liability coverage.[lxi]

3. Taxation

Federal business taxes are generally very simple—to calculate taxable income, a business typically subtracts its business expenses from its gross income and pays taxes on that amount. Businesses are then often able to gain profits from business deductions. However, under federal regulations, cannabis businesses are taxed on their gross income with no deductions.

Provision 280E of the Internal Revenue Code prevents companies from deducting expenses from gross income if the income is earned from “trafficking” a controlled substance. Enacted in 1982 as an effort to prevent drug dealers from using deductions to lessen their tax obligations and deter illegal drug trafficking. Under the provision, cannabis businesses can only write off cost of goods sold (COGS). However, the tax code strictly defines COGS and excludes common expenses such as rent, payroll, employee benefits, and supplies. Cannabis businesses are, however, allowed to claim tax credits. This includes discounts from vendors, housing credits, and research and development credits—all of which can be used to offset a portion of their taxable income.

Unable to write off normal business expenses under 280E, cannabis businesses often have tax burdens much higher than their traditional counterparts. In January 2015, the IRS issued an internal memorandum that imposed strict interpretation of Section 280E as it applies to state-legal cannabis businesses, rejecting many of the tax deductions that these businesses had previously made.[lxii] This is true even if they are compliant with the laws of the state they operate in.

Critique of Taxation Policy Options

Section 280E affects all businesses that engage in the cultivation, sale, or processing of cannabis plants and products. Its resulting tax can be 70% or higher, which creates a difficult financial obstacle, particularly for minority entrepreneurs, who often have less access to financial resources.[lxiii] Given the challenges that minority business owners often face in accessing resources for business, the tax provision only allows those who can afford the substantial burden of it participate in the market, which are often large, white-owned corporations.

Tax penalties collected under 280E generates millions of tax dollars for the federal government. Yet, little is known about how these taxes are used. But what is known is that the provision creates huge barriers for legally operating cannabis businesses and can be an even greater impediment to minority businessowners. Instead, taxes collected under 280E should be used for restorative drug war programs, including funding and promoting social equity in the legal cannabis space.

Overall, Section 280E, combined with limited access to financial relief, puts minority cannabis businesses at an extreme financial disadvantage. Unless the federal government takes steps to promote the growth of these businesses and provide them with the resources needed to succeed, financial obstacles will remain stacked against minority cannabis businessowners.

Taxation Policy Recommendations

As more states choose to establish a regulatory framework for legal cannabis businesses, the federal government should reconsider its stance to hold such businesses to a different economic standard as other businesses. Amending Section 280E in the following ways will help alleviate some of the adverse effects it has on minority business owners and social equity initiatives:

- Amend 280E to exclude its application to state-legal cannabis operations. Several legislative proposals could make Section 280E inapplicable to cannabis businesses operating legally under state law. Some involve rescheduling cannabis as a Schedule III controlled substance or de-scheduling it altogether. Others would simply exempt cannabis businesses operating compliant with state law.

- Fund social equity causes. Revenue collected under the 280E provision should be used to fund restorative justice efforts to help those harmed by the War on Drugs, including capital for minority cannabis businessowners. Although it is difficult to estimate the total taxes overpaid by cannabis businesses, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated in a 2017 letter sent to Senator Cory Gardner (R-CO) that repealing 280E would lower federal receipts by up to $5 billion over ten years.[lxiv] For as long as the provision is valid, funds collected under it should be used to repair the related harms of the federal government’s War on Drugs.

Conclusion

The century-long prohibition of cannabis has long been rooted in racist efforts to criminalize Black people and other communities of color. Policymakers, with the help of the media, pushed racially charged narratives about the potential of cannabis to cause violence and crime, particularly among groups of color. While progress patients, activists, and businessowners have made for decades toward opening a thriving legal cannabis market are realized in most states across the U.S., much work is still needed to reduce the harm of disproportionate drug policy enforcement. Policymakers and those profiting from sale of legal cannabis have a responsibility to ensure the economic empowerment of the communities most impacted, and a socially equitable cannabis industry can create lasting restorative justice. Although the end of the federal prohibition is unlikely anytime soon, the federal government can still take steps to create a diverse, equitable, and inclusive cannabis industry. This includes developing a social equity model and addressing areas of concern to minority business owners in the industry.

[1] Legally, marijuana is cannabis that contains more than 0.3% of the cannabinoid Tetrahydrocannabinol, also known as THC. Hemp, another type of cannabis plant, has 0.3% or less THC. Both marijuana and hemp are cannabis plants. Throughout this paper, cannabis will be used to refer to all products—including the dried leaves and flowers, dried resin, oil, and other extracts—of the Cannabis sativa, Cannabis indica, or Cannabis ruderalis plant. Although the dried leaves of the cannabis plant that are usually smoked in a joint or bong, is most referred to as “marijuana,” this paper will not use that term to describe products of the cannabis plant. As discussed later, the development of the term marijuana includes a controversial and racially charged history. As a result, the author only uses the term “marijuana” where there is appropriate historic or legislative context.

[2] While the definition of social equity can vary, depending on context, it generally means advancing justice and fairness through social policy. Rather than creating equal opportunities, social equity acknowledges and aims to correct systemic inequalities to level the playing field.

[3] Anslinger contacted 30 scientists for scientific evidence to support his claims that cannabis was dangerous, and 29 denied those claims. Yet, he presented the findings of the single expert who would agree with his position to campaign for its prohibition. See Adams, supra note 15.

[4] Following its 1839 introduction to Western medicine by William O’Shaughnessy, cannabis become a popular ingredient in American pharmacy medical preparations in the late 19th century. However, after the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Mexican immigrants increasingly came to the U.S. and became associated with the recreational use of cannabis. By the Great Depression, massive unemployment and increased public resentment of Mexican immigrants grew as well as public concern about the potential problem of “marijuana,” a term used by prohibitionists that “emphasized the drug’s foreignness to white Americans and appealed to the xenophobia of the time.” See Gieringer, D. H. (1999). The Forgotten Origins of Cannabis Prohibition in California. Contemporary Drug Problems, 26(2), 237–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/009145099902600204. See also Public Broadcasting Service, supra note 18.

[i] Kveen, B. (2023). (rep.). New State Markets Could Inject an Additional $18 Billion Annually into U.S. Legal Cannabis Market by 2030. New Frontier Data . Retrieved from https://newfrontierdata.com/cannabis-insights/new-state-markets-could-inject-an-additional-18-billion-annually/.

[ii] Morrissey, K. (2022). (rep.). New State Markets Could Boost U.S. Legal Cannabis Sales to $72B by 2030. New Frontier Data . Retrieved from https://newfrontierdata.com/cannabis-insights/new-state-markets-could-boost-u-s-legal-cannabis-sales-to-72b-by-2030/#:~:text=Media%20Access%E2%80%8B-,New%20State%20Markets%20Could%20Boost%20U.S.%20Legal,to%20%2472B%20by%202030&text=Based%20on%20New%20Frontier%20Data’s,%2472%20billion%20in%20that%20year.

[iii] Wallace, A. (2021, October 28). Cannabis Is One Industry That’s Actually Coming Out of Covid Even Stronger. CNN. Retrieved from https://www.cnn.com/2021/10/28/business/cannabis-booming-industry-mjbizcon/index.html. See also Holland, F. (2021, April 20). Cannabis Is One of the Fastest Growing Industry in the U.S. CNBC. broadcast. Retrieved from https://www.cnbc.com/video/2021/04/20/cannabis-is-one-of-the-fastest-growing-industry-in-the-u-s.html#:~:text=April%2020%20marks%20the%20unofficial,CNBC’s%20Frank%20Holland%20reports.

[iv] Marijuana Business Daily. (2017). (rep.). Women & Minorities in the Marijuana Industry. Retrieved from https://mjbizdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Women-and-Minorities-Report.pdf.

[v] Id.

[vi] Barcott, B., Whitney, B., & Bailey, J. (2021). (rep.). Jobs Report 2021. Leafly. Retrieved from https://leafly-cms-production.imgix.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/13180206/Leafly-JobsReport-2021-v14.pdf.

[vii] Edwards, E., Greytak, E., Madubuonwu, B., Sanchez, T., Beiers, S., Resing, C., Fernandez, P., & Galai, S. (2020). (rep.). A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform. American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/report/tale-two-countries-racially-targeted-arrests-era-marijuana-reform.

[viii] Id.

[ix] Littlejohn, A., & Green, E. (2022). (rep.). National Cannabis Equity Report: 2022. Minority Cannabis Business Association.

[x] Deitch, R. (2003). In Hemp: American History Revisited: The Plant with a Divided History (p. 7). essay, Algora Pub.

[xi] Tara, B. C. (2003). The Argument for The Legalization of Industrial Hemp. San Joaquin Agricultural Law Review, 13, 85–103. See also Deitch, supra note 10 at 16.

[xii] Deitch, supra note 10 at 26.

[xiii]Heimlich, R. (2019, December 30). Nearly Half Support Legalization of Marijuana. Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2012/11/12/nearly-half-support-legalization-of-marijuana/. See also Jones, J. M. (2022). (rep.). Marijuana Views Linked to Ideology, Religiosity, Age. Gallup. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/405086/marijuana-views-linked-ideology-religiosity-age.aspx.

[xiv] White, K. M., & Holman, M. R. (2012). Marijuana Prohibition in California: Racial Prejudice and Selective-Arrests. Race, Gender & Class, 19(3/4), 75–92. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43497489.

[xv] Adams, C. (2016, November 17). The Man Behind the Marijuana Ban for All the Wrong Reasons. CBS News. Retrieved from https://www.cbsnews.com/news/harry-anslinger-the-man-behind-the-marijuana-ban/.

[xvi] Id.

[xvii] Halperin, A. (2018). Marijuana: Is It Time To Stop Using a Word With Racist Roots? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jan/29/marijuana-name-cannabis-racism.

[xviii] Public Broadcasting Service. (1998). Marijuana Timeline: Busted-America’s War on Marijuana. PBS Frontline. Retrieved from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/dope/etc/cron.html.

[xix] Institute of Medicine. 1992. Treating Drug Problems: Volume 2. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/1971.

[xx] Edwards, E., Greytak, E., Madubuonwu, B., Sanchez, T., Beiers, S., Resing, C., Fernandez, P., & Galai, S. (2020). (rep.). A Tale of Two Countries: Racially Targeted Arrests in the Era of Marijuana Reform. American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/report/tale-two-countries-racially-targeted-arrests-era-marijuana-reform.

[xxi]Id.

[xxii] Solomon R. (2020). Racism and Its Effect on Cannabis Research. Cannabis and cannabinoid research, 5(1), 2–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/can.2019.0063.

[xxiii] Craigie, T.-A., Grawert, A., Kimble, C., & Stiglitz, J. E. (2020). (rep.). Conviction, Imprisonment, and Lost Earnings: How Involvement with the Criminal Justice System Deepens Inequality. Brennan Center for Justice. Retrieved from https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/conviction-imprisonment-and-lost-earnings-how-involvement-criminal.

[xxiv] Id.

[xxv] Race and the Drug War. Drug Policy Alliance. (2023). Retrieved from https://drugpolicy.org/issues/race-and-drug-war.

[xxvi] Criminalization & Racial Disparities. Vera Institute of Justice. (2023). Retrieved from https://www.vera.org/ending-mass-incarceration/criminalization-racial-disparities.

[xxvii] Betsy, P. (2021, October 28). Ending the War on Drugs: By the numbers. Center for American Progress. Retrieved from https://www.americanprogress.org/article/ending-war-drugs-numbers/. See also Wagner, P., & Rabuy, B. (2015). (rep.). Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2015. Northampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved from https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie2015.html.

[xxviii] Drug Policy Alliance. (2023). A History of the Drug War. Drug Policy Alliance. Retrieved from https://drugpolicy.org/issues/brief-history-drug-war.

[xxix] Vera Institute of Justice. (2023). Ending mass incarceration. Vera Institute of Justice. Retrieved from https://www.vera.org/ending-mass-incarceration?ms=awar_comm_all_grant_BS22_ctr_AP2&utm_source=grant&utm_medium=awar&utm_campaign=all_AP2&gclid=Cj0KCQiA3eGfBhCeARIsACpJNU81hPfROOH-ZDx15PAD3CZgyjeKMqJ6Pyvvc6Ds-jIkAiAYeM3_I1waAlukEALw_wcB.

[xxx] Id.

[xxxi] Drug Policy Alliance. (2021). (rep.). Drug War Statistics. Retrieved from https://drugpolicy.org/issues/drug-war-statistics?ms=5B1_22GoogleSEM&utm_source=GoogleSEM&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=SEM&cid=7011K000001SFcBQAW&gclid=CjwKCAiA9NGfBhBvEiwAq5vSy6e1Hts5jkkHkfbV8llnjHpENlPs7IXUiBgz2QHmBpUAgbZUXKnF1xoClA0QAvD_BwE.

[xxxii] Marijuana Business Daily. (2017). (rep.). Women & Minorities in the Marijuana Industry. Retrieved from https://mjbizdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Women-and-Minorities-Report.pdf. Marijuana Business Daily, supra note 4.

[xxxiii] Id.

[xxxiv] Craigie, supra note 23.

[xxxv] Dionissi Aliprantis and Daniel Carroll, What Is Behind the Persistence of the Racial Wealth Gap?, Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 2019, 1, https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/2019-economic-commentaries/ec-201903-what-is-behind-the-persistence-of-the-racial-wealth-gap.aspx. See also William Darity Jr. et al., What We Get Wrong About Closing the Racial Wealth Gap, Samuel DuBois Cook Center on Social Equity, April 2018, https://socialequity.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/what-we-get-wrong.pdf.

[xxxvi] Craigie, supra note 23.

[xxxvii] Taylor, A. (2022, April 26). Black Cannabis Entrepreneurs Account for Less Than 2% of the Nation’s Marijuana Businesses. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/nickkovacevich/2019/02/01/the-hidden-costs-of-the-cannabis-business/?sh=6e21f9f57da3.

[xxxviii] Littlejohn, supra note 9.

[xxxix] Kveen, supra note 1.

[xl] Barcott, B., supra note 6.

[xli] Hanson, K. (2020, November). Social Equity in State Regulated Cannabis Programs. Presentation for the Washington State Senate Labor & Commerce Committee. Retrieved from https://app.leg.wa.gov/committeeschedules/Home/Document/223893.

[xlii] Littlejohn, supra note 9.

[xliii] Littlejohn, A., supra note 9. See also WM Policy. (n.d.). (rep.). Social Equity in Cannabis: Advancing Restorative & Equitable Cannabis Policies. Retrieved from https://wmpolicy.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Social-Equity-in-Cannabis-Policy-Paper-WM-Policy.pdf.

[xliv] Quinton, S. (2021, January 15). Black-Owned Pot Businesses Remain Rare Despite Diversity Efforts. Pew Charitable Trusts. Retrieved from https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2021/01/15/black-owned-pot-businesses-remain-rare-despite-diversity-efforts.

[xlv] Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Marijuana Related Businesses Metrics (updated through September 2022) (2022). Retrieved from https://www.fincen.gov/frequently-requested-foia-processed-records.

[xlvi] New Dawn Risk. (2021). (rep.). Understanding and Opening Up the U.S. Cannabis Insurance Market. Retrieved from https://www.newdawnrisk.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Cannabis_report-FINAL.pdf.

[xlvii] Hatzopoulos, A. (2020, July 13). The Cost of Cash for Unbanked Cannabis Businesses. Forbes. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesfinancecouncil/2020/07/13/the-cost-of-cash-for-unbanked-cannabis-businesses/?sh=4ce94c58f4dd.

[xlviii] Quinton, supra note 44.

[xlix] Kerr, William R., and Ramana Nanda. 2011. “Financing constraints and entrepreneurship.” Handbook of Research on Innovation and Entrepreneurship eds. David B. Audretsch, Oliver Falck, Stephan Heblich and Adam Leder: 88.

[l] Packer, Cat and Title, Shaleen and Crockett, Rafi Aliya and Dawson, Dasheeda, Not a SAFE Bet: Equitable Access to Cannabis Banking, An Analysis of the SAFE Banking Act (August 11, 2022). Ohio State Legal Studies Research Paper No. 721, 2022, Drug Enforcement and Policy Center, August, 2022, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4188072 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4188072.

[li] Quinton, supra note 44.

[lii] Id.

[liii] Blanchflower, David G., P. Levine and D. Zimmerman. 2003. “Discrimination in the small business credit market”, Review of Economics and Statistics, November, 85(4), pp. 930-943.

[liv] Broady, K., McComas, M., & Ouazard, A. (2021). (rep.). An Analysis of Financial Institutions in Black-Majority Communities: Black Borrowers and Depositors Face Considerable Challenges in Accessing Banking Services. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/an-analysis-of-financial-institutions-in-black-majority-communities-black-borrowers-and-depositors-face-considerable-challenges-in-accessing-banking-services/.

[lv] Brown, J. (2023). (rep.). Black History Month survey: Legacy and Community Prevail Against Social and Economic Inequalities. Intuit QuickBooks. Retrieved from https://quickbooks.intuit.com/r/small-business-data/black-history-month-survey-2023/.

[lvi] Van Tol, J. (2020, February 21). Reduce lending in low-income neighborhoods? Incredibly, the government has a plan that could help banks do that. The Hill. Retrieved from https://thehill.com/blogs/congress-blog/politics/484063-the-government-has-a-policy-that-could-help-banks-reduce-lending/.

[lvii] Broady, supra note 54.

[lviii] BPI Statement on Proposal to Modernize the Community Reinvestment Act. (2022, May 5). Bank Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://bpi.com/bpi-statement-on-proposal-to-modernize-the-community-reinvestment-act/.

[lix] New Dawn Risk. (2021). (rep.). Opportunity Knocks at Last in the U.S. Cannabis Insurance Market. Retrieved from https://www.newdawnrisk.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/US-Cannabis-Report-New-Dawn-Risk-2021-Edition.pdf.

[lx] New Dawn Risk, supra note 46.

[lxi] New Dawn Risk, supra note 59.

[lxii] National Cannabis Industry Association. (2015). (working paper). Internal Revenue Code 280E: Creating an Impossible Situation for Legitimate Businesses. Retrieved from https://thecannabisindustry.org/uploads/2015-280E-White-Paper.pdf.

[lxiii] Boesen, U. (2021). (rep.). https://taxfoundation.org/federal-cannabis-administration-opportunity-act/. The Tax Foundation. Retrieved from https://taxfoundation.org/federal-cannabis-administration-opportunity-act/.

[lxiv] Joint Committee on Taxation, Letter to Sen. Cory Gardner, Dec. 1, 2017, https://newtax.files.wordpress.com/2018/12/370531229-Senator-Gardner-280E-Score-12-04-2017.pdf.