By Malik Neal, NREI John Lewis Social Justice Fellow

Kathy Winsor often sits in the dark in her living room wearing extra layers to keep warm. For Winsor, this almost daily ritual is not a choice but a necessity—an economical way to keep her electric and gas bills low as her unemployment benefits expire next month. “I’ve never been unemployed like this,” she said, nearly three months after losing her job as a home healthcare aide caring for a woman who recently moved into a nursing home. Winsor, a 49-year-old resident of Wadesboro, North Carolina, a rural Black town, lives in a state with some of the strictest eligibility requirements and one of the lowest cap maximums for unemployment benefits. She receives $250 per week in benefits to support herself. However, as these benefits are insufficient to meet her most basic needs, Winsor has had to resort to other means. To make ends meet, Winsor now carefully apportions her meals each morning and has recently begun collecting cans and cardboard on weekends in her neighborhood for extra income. But, as she approaches the end of her 12th week of unemployment benefits, she knows the worst is yet to come. A sudden cut-off in benefits will likely force her to sell her living room furniture for her mortgage payment of $561, but even that is only a temporary solution. “I’m overwhelmed,” she said, surrounded by photos of her two grandchildren. “I don’t want to have to go to a women’s shelter. I’ve worked my whole life. I’ve taken care of myself since I was 14, and now I feel like I may not be able to care for myself anymore.”[1]

Winsor’s story is emblematic of a much larger problem: for millions of jobless American workers, the vital lifeline of unemployment insurance has become increasingly more uncertain and inaccessible. The American unemployment insurance system was created during the Great Depression as a safety net for individuals who lost their jobs through no fault of their own and were actively seeking work. Its goal was to provide temporary financial support to unemployed workers to prevent them from falling deeper into poverty. Today, however, this goal seems increasingly out of reach. According to a 2019 analysis, only 28% of unemployed workers receive benefits, a percentage that has dropped over the past two decades.[2] Additionally, benefit amounts, on average, have fallen to less than one-third of prior wages.[3] The decline in funding for the unemployment insurance system, combined with rising living costs and the length of time people are out of work, has led one U.S. senator to conclude that the program is inadequate for the needs of a 21st-century economy.[4]

While there is much literature discussing the shortcomings of unemployment insurance (“UI”),[5] this paper focuses on how the current administration of UI, in practice, exacerbates racial inequality. Using data from the Department of Labor and the U.S. Census Bureau, this paper will address the following questions: 1) to what extent are disparate UI treatments and benefits attributed to race; 2) what is the primary source of the racial gap in the administration of UI; and 3) what reforms to the design of the unemployment insurance system could reduce that gap. This paper’s analysis is primarily restricted to the years 2015-2019 to avoid any statistical anomalies associated with both the unprecedented job loss caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and the creation of new, temporary pandemic-specific UI programs.[6] The paper finds a correlation between states with systemically stricter unemployment insurance rules and those with large Black populations. In these states, the recipiency rate, the cap on weekly benefits claimants can receive, and the annual benefits paid are all lower.

Furthermore, the paper argues that the difference in state-specific rules, particularly in Southern states, is a significant factor in Black claimants receiving lower and fewer benefits than white claimants. It concludes that addressing racial inequality in unemployment insurance requires federal action. The author recommends that Congress mandate states to increase the duration of benefits and broaden eligibility by implementing new national standards, restructuring UI financing mechanisms, and supporting more comprehensive community outreach and data collection. Without federal action, the unemployment insurance system will continue to disadvantage Black Americans, who stand to benefit the most from such relief. In the end, reforming unemployment insurance is a racial justice issue.

This paper is structured in five parts. The first section briefly analyzes unemployment insurance and how Black Americans have been disadvantaged since the program’s inception. The second section details the predicament of Black workers, who are disproportionately unemployed and underemployed. The third section provides institutional context by discussing the operations and challenges of the unemployment insurance system. The fourth section uses UI claims data to demonstrate how Black Americans fare worse than their white counterparts regarding who receives UI and how much they receive. Finally, the author proposes a list of policy recommendations for Congress to ensure that the unemployment insurance system is both accessible and efficient and a reliable resource for all Americans.

I. Flawed By Design: Race & History of Unemployment Insurance

To fully grasp the current inequalities in the administration of unemployment insurance, it is essential to understand its origins. Congress created unemployment insurance in America in 1935 as a joint federal-state program to financially support jobless workers during the Great Depression. Despite the devastating economic effects of the Great Depression on all, the newly created unemployment insurance program limited benefits to “only those workers regularly employed in commerce and industry.”[7] This definition, which Members of Congress from the Deep South demanded as a condition of their support, expressly excluded agricultural and domestic workers, who were disproportionately Black Americans.[8] Thus, when it was first implemented, unemployment insurance excluded approximately 65% of the Black workforce, resulting in a program that primarily benefited white, male, full-time workers.[9] It was not until 1954, twenty years later, that coverage fully extended to agricultural and domestic workers.

Black Americans were also largely excluded from unemployment insurance due to another compromise made by lawmakers. To secure enough votes to pass the New Deal legislation, Northern Democrats agreed to cede control of unemployment insurance to the states, resulting in Southern states having a powerful mechanism to control the allocation of public funds. Unlike Social Security, which remains federally operated, unemployment insurance is still primarily administered by states, which can determine who qualifies for benefits, how generous the benefits are, and how strict the requirements are. The decentralized structure of UI, similar to other systems controlled by the state, has led to a disproportionate exclusion of Black Americans from the benefits of the welfare state.[10]

Historians—have and continue to—debate whether the exclusion of more than half of Black workers from UI was due to racism or an incidental and administrative necessity. Some scholars argue that the exclusions resulted from the government not having the means to include agricultural and domestic workers and that unemployment insurance programs in other countries made similar exclusions.[11] Still, others argue that Congress intentionally excluded Black workers to protect the Southern segregationist power structures and disempower Black communities.[12] Such scholars also point to the warnings of prominent Black advocates at the time, such as Charles Hamilton of the NAACP, who cautioned Congress that the UI program and others like it would leave a “hole just big enough for the majority of Negroes to fall through.”[13] Regardless of the motivation or intent behind the exclusion of Black workers, the disparate impact of the UI program on Black Americans is undeniable. Racial inequality was built into the program’s structure, keeping most Black Americans at arm’s length while primarily benefiting white Americans.

- First Fired, Last Hired: Black Employment

The shortcomings of America’s unemployment insurance system continue to pose a significant challenge for Black Americans due to disproportionately high unemployment rates within the Black community. Black workers are affected by what some economists have labeled as the “first fired, last hired” phenomenon – i.e., they are the first to lose their jobs, and their unemployment rates are the last to recover even as the economy improves.[14] Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that unemployment disparities persist during times of both widespread job loss and economic growth. In fact, from 1972—when unemployment data disaggregated by race first became available— to 2019, Black Americans have consistently had unemployment rates twice that of white Americans.[15] This pattern of racial disparity in the labor market persists across all categories, including gender, age, and veteran status.[16] The gap in unemployment rates between Black and white workers is even more pronounced in cities with a majority, or near majority, Black population. For example, the Black unemployment rate in Atlanta and New Orleans is over four times higher than the white rate. Washington, D.C. has the highest Black-white unemployment ratio gap, at 6:1.[17]

Some economists have attempted to explain the Black-white unemployment gap by pointing to differences in skills and education.[18] For example, in 2019, 47% of white Americans obtained some college degree, while only 30% of Black Americans did.[19] According to this view, Black people, on average, have less educational attainment, thus leading to higher unemployment rates. However, this hypothesis fails to explain the unemployment disparities between Black and white Americans fully. Even when Black Americans have achieved the same level of educational attainment as white Americans, their unemployment rates are still higher. For example, at 10.8%, Black people without a high school diploma have an unemployment rate that is more than twice as high as similarly situated white people at 4.9%. Even more striking, the unemployment rate for Black people with some college education (4.9%) is nearly the same for white people with no high school diploma.[20] These statistics suggest deeper, more structural causes behind the Black-white unemployment gap.

Recent research suggests that the causes behind the Black-white unemployment gap can be found in the lingering effects of systemic racism, including unequal school funding, mass incarceration, and hiring discrimination.[21] Hiring discrimination is a particularly significant barrier. A considerable amount of research using field experiments has demonstrated the existence of bias against Black Americans and other racial minorities in the hiring process.[22] A 2021 experiment, where researchers sent 83,000 fictitious job applications for entry-level positions at Fortune 500 companies, found that, on average, applications with distinctively Black names were 10% less likely to receive an invitation for an interview than comparable applications with white names.[23] Mass incarceration also significantly impacts Black participation in the labor market, particularly for Black men. Black Americans are more likely to be incarcerated than white Americans.[24] Further, people who have been formerly incarcerated face significant barriers to gaining and maintaining employment.[25] These structural barriers impede Black employment and contribute to disproportionately low Black wages and the overrepresentation of Black Americans in app-based and part-time jobs despite wanting full-time employment.[26] Put simply, given the precarious state of Black employment, federal unemployment insurance can and should serve as a critical tool for financial stability for Black workers.

- Background and Challenges of Unemployment Insurance

Throughout the years, the primary objective of the unemployment insurance program has remained unchanged: to partially replace wages for some recently unemployed workers through a federal-state insurance program. Although benefits vary by state, the average replacement rate—the share the state replaces based on a worker’s previous wages—is typically around 50%. The most common maximum duration of benefits is 26 weeks. Eligibility criteria and weekly benefit amounts vary significantly by state based on their respective UI rules. Before the pandemic, the number of Americans collecting unemployment peaked at around 1.8 million. However, the latest data indicates that 18.3 million people are receiving payments. [27]

Eligibility. The only criteria the federal government stipulates for persons seeking unemployment benefits is that claimants must:

- have lost a job through no fault of their own;

- be “able to work, available to work, and actively seeking work;”

- have earned enough sufficient income during a “base period earning” before unemployment[28]

States have broad discretion in applying these criteria. States can also add additional measures, such as the duration of prior employment and which professions are eligible. States are also free to determine how much previous income is “sufficient,” as well as the level and duration of benefits.

Benefits. Unemployment benefits typically come in the form of weekly payments. States generally set the Weekly Benefit Amount (WBA) between 30 – 50% of the claimant’s highest earning period before unemployment, but the percentage differs by state. In addition, states impose maximum caps on Weekly Benefit Amounts and determine the maximum duration for eligible claimants to collect benefits.

Funding. State and federal payroll taxes fund the UI system. The State Unemployment Tax Act (SUTA) tax is set and administered by states; thus, the amount taxed varies between states. The Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) tax is federally administered and is 6% of the first $7,000 of each employee’s wages. All state and federal unemployment funds are then deposited into the Unemployment Trust Fund overseen by the Department of Treasury and serves as a state’s UI account. States can also borrow funds from the federal government if they need to raise more revenue, but they must repay it within two years. [29]

Challenges

While many challenges plague the current administration of unemployment insurance, three are particularly noteworthy. First, the state administration of the program has effectively created 53 different unemployment insurance agencies with substantial variations in eligibility standards, verification protocols, and processing time.[30] The timeframe by which a claimant receives their first payment, for instance, is influenced significantly by where they live. For example, after the state introduced a new online unemployment claims system in Florida, only over half of the people who filed for benefits in 2020 received their first check within three weeks.[31] Such variations in processing time by state can be costly for people in need, especially during a crisis such as the pandemic.[32] Another challenge with state administration is the funding structure. As noted in the previous section, states rely partly on state taxes to cover unemployment insurance. Such an arrangement is challenging because some states, hoping to be more business-friendly, simply lower taxes, thus leaving their unemployment insurance programs underfunded. States are therefore incentivized to shorten benefits, reduce weekly benefits, and increase qualification hurdles, thus, narrowing the number of people who can receive benefits.[33]

A second challenge to the current UI system is that too few unemployed workers are eligible for benefits. In 2019, only 28% of all unemployed workers received UI benefits nationwide. The percentage of those receiving UI benefits also varies widely by state. Several factors drive the eligibility problem. Arguably the most important is the minimum earning threshold set by each state to meet eligibility. If the threshold is too high (as in many states), states exclude low-wage workers even if they have lost their job. Such a threshold is especially burdensome to Black Americans, who receive lower wages than white workers on average due to longstanding structural barriers and labor market discrimination.[34] Another factor contributing to increased ineligibility is a rigid requirement that workers must be involuntarily separated from work. While this requirement is sensible, it does not account for voluntary separations that are out of a worker’s control (such as a significant drop in work hours, excessively demanding work schedules, health reasons, partner relocation, childcare, etc.). In addition, while some states have broadened the work separation requirements, others have not, leading to lower rates of claimants receiving benefits.[35] The exclusion of unemployed workers such as gig workers, independent contractors, and part-time workers has also led many to fall through the cracks of the UI system.[36]

The final noteworthy challenge of UI is inadequate benefits and maximum duration caps. Scholars are questioning the current wage replacement rate of 50% in many states. They argue that more may be needed for low-wage workers, particularly those with dependents, who are more vulnerable to financial insecurity.[37] Additionally, the maximum duration of benefits varies significantly across states, with some capping at 12-16 weeks, disproportionately affecting Black workers who tend to have more extended periods of unemployment.[38] To address these issues, scholars propose accounting for income in benefits distribution and increasing the benefits and duration for a more comprehensive and efficient social safety net.[39]

- Findings & Analysis of Racial Inequality

To analyze the impact of race on the administration of unemployment insurance, this paper utilizes data from various sources, including state-specific guidelines, the U.S. Census American Community Survey, and the Benefits Accuracy Measurement program. The BAM program requires states to audit both accepted and rejected claims and submit the data to the Department of Labor. This publicly accessible data from the Department of Labor encompasses information from all states, including demographic details and general information on claimants. By comparing these data, the paper aims to demonstrate the extent of the racial gap in UI and the strength of the correlation between states with high percentages of Black residents and less favorable UI policies and administration. Ultimately, states with a higher proportion of Black residents are found to have less generous benefits for unemployed workers.

How Much UI Pays

One way to evaluate the effectiveness of a state’s unemployment insurance program is by analyzing the amount of benefits paid to claimants. Such an evaluation can be done by examining four key metrics: 1) the maximum weekly benefit; 2) the annual benefits paid; 3) the replacement rate; and 4) recipiency rates. The maximum weekly benefit refers to the maximum amount a claimant can receive through the state’s UI program. The annual benefits paid are calculated by determining the total amount of UI claims paid in a year divided by the number of claims in that state. The replacement rate is the percentage of a worker’s average weekly wages replaced by UI benefits. The higher the percentage, the more workers will be able to receive payments closer to their pre-unemployment wages. States have complete discretion over these four metrics, which leads to significant variations in UI policies and implementation across states.

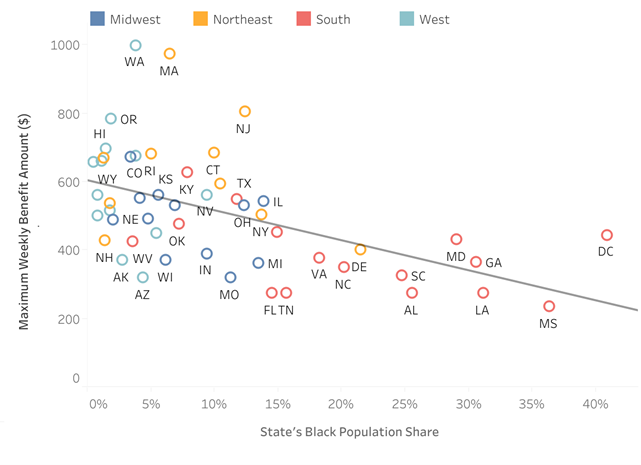

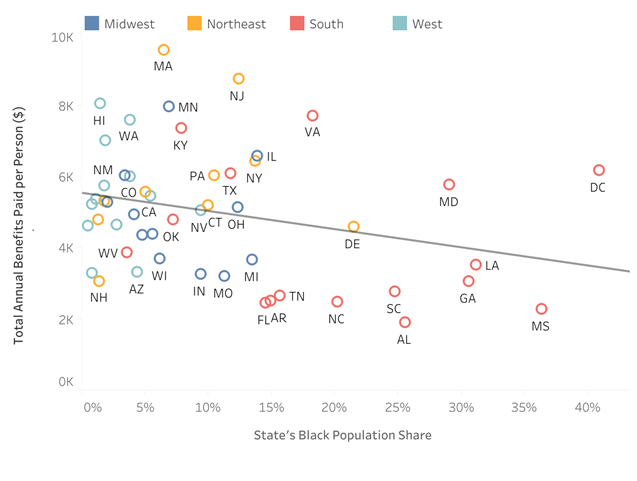

The differences in maximum weekly benefits between states are particularly striking. For example, the most generous state (Washington at $999) pays 4.25 times more than the least generous state (Mississippi at $235). Similarly, states like Alabama and Louisiana have maximum caps at $275, while New Jersey and Oregon have caps at $974 and $804, respectively. These variations between states also contribute to racial disparities. As Figure 1 illustrates, states with a higher proportion of Black residents, such as Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina, generally have among the nation’s lowest maximum weekly benefit amounts.[40] This pattern can also be seen in the annual benefits paid (See Figure 2). Lower benefits create more significant hardships for workers as they need more resources to meet their basic needs while unemployed and looking for work.[41]

Maximum Weekly Benefits v. Black Population (Figure 1)

Annual Benefits Paid Per Person v. Black Population (Figure 2)

In addition to the maximum benefits cap, replacement rates for unemployment insurance also determine how much a claimant can receive in a particular state. Various studies suggest that a replacement rate of wages around 60% – 70% (on par with international standards) is optimal in balancing the competing goals of providing a meaningful safety net and incentivizing work.[42] Only two states are close to that percentage. North Dakota and Iowa have the highest replacement rate at 48%. However, states like Louisiana, Tennessee, and North Carolina are at 31% or below. While the correlation is less striking than with the maximum weekly and annual benefits paid, the seven states with a Black population over 20% have replacement rates under 40%.

Who Receives UI Benefits?

Despite the higher unemployment rates among Black Americans, data shows that fewer Black workers receive unemployment insurance than other racial groups. An analysis of 2015-2019 American Survey data reveals that only 24% of unemployed Black workers received UI benefits, compared to 33% of white workers.[43] Even during the pandemic, when Congress expanded UI eligibility, the gap remained, with 13% of Black workers receiving benefits compared to 24% of white workers.[44]

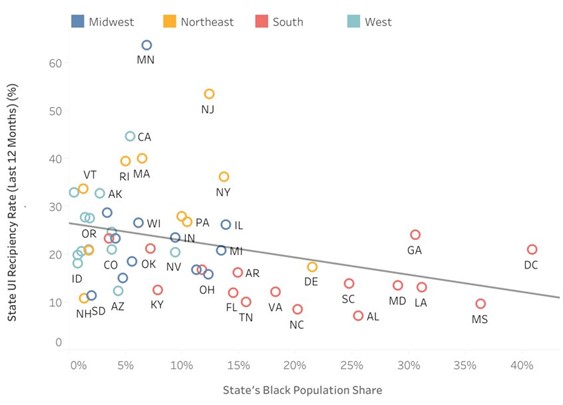

The low percentage of Black workers receiving unemployment insurance is due to structural barriers such as discrimination and poverty and geography. The states with the lowest UI recipiency rates, or the proportion of jobless workers receiving benefits from a state program, are primarily located in the South and have a higher proportion of Black residents (see Figure 3). For example, in 2019, only 7.7% of unemployed workers in Alabama (with a Black population of 26%) received benefits, while in Mississippi, the state with the highest proportion of Black residents (36%), only 10% of unemployed workers received benefits. In contrast, states like Minnesota and New Jersey had recipiency rates of 67% and 51%, respectively.[45]

UI Recipiency Rate v. Black Population (Figure 3)

A similar pattern can be observed in denial rates for UI benefits. In 2019, eight of the nine states with the highest Black population percentages had a higher rate of denied UI claims, with rates over 30%. The denial rates in South Carolina and Mississippi were particularly concerning, with 81% and 88% of claims being denied, respectively.[46] While it is challenging to pinpoint the specific reasons for denied claims, states with high denial rates tend to have strict eligibility requirements, which exclude low-wage workers and part-time workers, as well as mandate short benefit duration periods.[47]

- Policy Recommendations

The racial inequalities in America’s unemployment insurance system highlighted in the previous section strongly suggest that structural reform is needed. This dismal truth is that existing unemployment insurance— a patchwork of outdated state systems with little to no federal regulation—is an inadequate and unreliable safety net for millions of Americans. According to a 2021 U.S. Census Bureau survey, nearly one out of three households (31%) receiving unemployment insurance still had difficulty paying household expenses.[48] For Black Americans, the problem is even more pronounced. Due primarily to uneven state policies, Black workers are 24% less likely to receive UI benefits, and when they do, their payments are 11% lower than white Americans.[49]

While the shortcomings of UI are not new, the COVID pandemic exposed UI’s fragility in new ways. As unemployment rates quadrupled to 14.8 %—the highest since data collection began in 1948—UI claims skyrocketed to unprecedented levels, resulting in nearly every state struggling to send out benefits.[50] But if the pandemic’s early months laid bare UI’s failures, later months also revealed its potential. In response to the pandemic, Congress implemented the most significant expansion in UI benefits in U.S. history. It created new temporary programs – i.e., Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), and Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) – to expand eligibility requirements, extend the duration of benefits, and increase weekly benefits.[51] These changes to UI, which expired in September 2021, offer an important lesson: the federal government can and must take bold action to ensure UI works fairly and adequately for all Americans.

In 2021, Senators Ron Wyden (D-Oregon), Michael Bennet (D-Colorado), and Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) introduced the Unemployment Insurance Improvement Act to harmonize varying states’ UI benefits.[52] The recommendations below include some of these proposals and new ones to address racial inequality more directly. In the absence of state action, Congress should:

Set minimum federal standards that state UI programs must meet.

- Expand benefit duration: The duration of unemployment insurance benefits has been a point of contention for many states. Historically, all states provided a maximum of 26 weeks of benefits.[53] However, in recent years, ten states have reduced their benefit duration, with some even cutting it in half (i.e., North Carolina). This trend will likely continue as more states (e.g., Wisconsin, Louisiana, Oklahoma) consider similar legislation as recent as 2022.[54] These reductions in benefit duration disproportionately affect Black workers, who tend to experience more extended periods of unemployment at, on average, 27 weeks or longer.[55] Congress should therefore set a national standard and mandate that states offer at least 28 weeks of benefits—the national average unemployment period—and adjust the duration based on the national unemployment rate.[56]

- Increase benefits: The current method for calculating UI benefits, which solely relies on past wages, does not adequately address the needs of workers, particularly those in the Black community who are disproportionately employed in low-wage jobs.[57] To address this issue, states should be required to adopt a more progressive, advanced replacement formula that increases the replacement rate based on wages (see Table 1), capping at covering 85% of wages for low-wage workers.[58] Additionally, federal law should mandate that states index benefits with inflation and cost of living, similar to Social Security, and provide allowances for dependents.[59] This approach would help to alleviate economic insecurity and reduce racial disparities in the UI system.

| Proposed progressive replacement rates formula for unemployment benefits by earning levels (Table 1) | |

| Earning Levels | Replacement Rate |

| Between 0% and 50% of state average weekly wages | 85% |

| Between 51% and 100% of state average weekly wages | 70% |

| Over 100% of state average weekly wages | 50% |

- Broaden eligibility: Federal law should prohibit states from implementing restrictive eligibility requirements. Congress should prohibit denying benefits to part-time workers, disproportionately Black and Latinx, and close the independent contractor loophole. Congress can do so most effectively by requiring states to use the ABC employee classification test currently employed by thirty-three states. The test, which is protective of workers, considers a worker an employee—and not an independent contractor—unless the hiring entity can satisfy three rigid requirements. It also shifts the burden to the employer to prove a worker is an independent contractor rather than on the worker to prove they are an employee.[60] Additionally, Congress should mandate that the good-cause job separation reasons be expanded to include harassment, safety hazards, family care, and other health-related issues. The Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, which temporarily expanded eligibility standards, demonstrated that such changes can increase Black and Latinx workers receiving benefits.[61]

Restructure the financing of the UI system to deliver benefits more effectively.

- Broaden taxable wage base: The current funding structure of the unemployment insurance program must be improved to ensure better benefits for those in need. The current model, which relies on evenly split payments from federal and state revenue, has resulted in benefits limitations and a lack of sustainability. Moreover, the pressure on states to keep tax rates low to attract businesses has led to further reductions in UI benefits. To address these issues, Congress should increase UI’s federal taxable wage base to a level equal to the current Social Security wage ($142,800) and index it to inflation. Broadening the taxable wage base would increase the funds collected to support the UI system, allowing for lower UI tax rates and a more sustainable approach.[62] With more funds available, the UI system would be better equipped to support the unemployed while reducing the tax burden on employers and employees.

- Base state fund targets on industry-adjusted per capita targets: The current method used by the federal government to set state fund targets for UI, the high-cost multiple method, is a one-size-fits-all formula and may not accurately reflect the needs of different states and industries. This method, which multiplies a state’s highest cost of benefits by a predetermined factor, can lead to underfunding or overfunding UI systems.[63] A more effective approach would be to use a state industry-adjusted per capita target method, which would take into account the number of people in the state’s workforce and the characteristics of the industries in the state.[64] This method would make unemployment insurance more sustainable and address the specific labor market needs of areas where Black Americans are disproportionately represented.

Improve equitable access to unemployment insurance and collect accurate data.

- Prioritize targeted grants for community outreach: In August 2022, The Department of Labor declared the availability of $260 million in grants to states to enhance fair access to unemployment insurance through public awareness and service delivery.[65] Such grants are a positive step towards resolving the problem of access to unemployment insurance and should be continued. However, to guarantee that the funds reach states which require them the most, the allocation should be based on a state’s recipiency rate, with priority given to Southern states that disproportionately have low rates. Such a targeted approach will better aid the people and communities that need these essential resources.

- Mandate employers to inform workers of UI benefits: To improve access to unemployment insurance (UI) benefits, the Department of Labor (DOL) should create and enforce regulations requiring employers to inform departing employees of their rights to unemployment insurance and provide clear instructions on how to apply. Informing employees could include providing written materials or directing employees to online resources. Furthermore, DOL should mandate that employers train their human resources staff or designated employees on the UI process to ensure employers can provide accurate and comprehensive information to employees seeking benefits.

- Collect and share data: To effectively address African Americans’ disparities in accessing unemployment insurance (UI), we must have accurate and comprehensive data on key issues. Therefore, states should prioritize collecting and disseminating data promptly on application backlogs, call center wait times, application rates, and the effect of system updates on payment timeliness, denials, and delays. Furthermore, it is essential to ensure that this data is analyzed by race, ethnicity, and gender, as well as on a county and neighborhood level, to gain a deeper understanding of the specific challenges different communities face and develop targeted solutions to improve UI access for African Americans.

Some may contend that the above recommendations are too ambitious, while others need to be more ambitious. For instance, a frequent criticism of increasing the generosity of unemployment insurance is that it reduces the motivation of individuals to find work.[66] However, recent research from the Chicago Federal Reserve challenges this argument. The report, which measured the number of hours searched and applications submitted by claimants, found that individuals collecting benefits searched twice as much as those not collecting.[67] In another study, Peter Gagong compared job growth in states that ended pandemic unemployment insurance programs early to those that kept them throughout most of the pandemic. The study found that job growth in both groups of states was remarkably similar.[68] Some have also suggested that the federal government should fully finance unemployment insurance as it does for Social Security.[69] While this would eliminate variations among states, it would also entail significant increases in federal spending and taxes, making it unfeasible in the near term. The financing proposals put forward in this paper offer a more feasible approach to increasing federal involvement and support without making unemployment insurance a federal program entirely.

It is important to note that the policy recommendations presented in this paper, which focus on addressing racial inequality and center the Black community, should not be viewed as exclusively benefiting Black Americans. The underlying premise of this paper is that closing the racial gap in unemployment insurance through more generous policies will ultimately benefit all working-class Americans. Improving unemployment insurance for Black people, who are disproportionately affected by unemployment, is not a zero-sum game.[70] The unemployment insurance system failing Black Americans and other communities of color is failing us all.

*****

The outcome of Kathy Winsor’s situation remains uncertain. Whether she was able to keep up with her mortgage payments or if her constant fear of living in a women’s shelter came true is unknown. However, it is clear that Winsor’s predicament, as unfortunate as it was, could have been avoided. Her story highlights the unemployment insurance system’s inadequacies, uncertainties, and inequalities. Due to the varying policies and administration of different states, where one resides— not their need—is the deciding factor in determining the frequency and amount of benefits received. Unfortunately, states with higher proportions of Black residents tend to have the least generous UI programs, leading Black Americans to fare worse than their white counterparts. To address this pressing issue, Congress must take action by establishing minimum standards, restructuring the financing mechanisms of UI, and improving access and outreach to Black other marginalized communities. Only then can the gaping gaps in the safety net of UI be filled, and stories like Kathy Winsor’s can become a thing of the past.

Endnotes

[1] This story was adapted from a collection of stories of people impacted by federal unemployment insurance compiled by the Ways & Means Committee of the House of Representatives. Ways and Means Committee. (2013, December 27). The Stories of Americans Losing Federal Unemployment Insurance. https://waysandmeans.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/stories-americans-losing-federal-unemployment-insurance

[2] Porter, E., & Russell, K. (2021, August 19). How Our Unemployment Benefits System Failed. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/21/business/economy/unemployment-insurance.htm

[3] Ibid

[4] Bennet, Wyden Unveil Unemployment Insurance Overhaul. Michael Bennet. (2021, April 14). https://www.bennet.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2021/4/bennet-wyden-unveil-unemployment-insurance-overhaul

[5] See, Reforming Unemployment Insurance. National Employment Law Project, June 2021, https://s27147.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/Reforming-Unemployment-Insurance-June-2021.pdf; Goger, Annelies, et al. Unemployment Insurance Is Failing Workers during COVID-19. Here’s How to Strengthen It. Brookings Institution, 9 Mar. 2022, https://www.brookings.edu/research/unemployment-insurance-is-failing-workers-during-covid-19-heres-how-to-strengthen-it/; von Wachter, T. (2019). Unemployment Insurance Reform. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 686(1), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716219885339

[6] See Congressional Research Services. (2020, April 9). Unemployment Insurance Provisions in the CARES Act. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11475

[7] Larry DeWitt, “The decision to exclude agricultural and domestic workers from the 1935 Social Security Act,” Social Security Bulletin 70 (4), 2010, p 49–68, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/ssb/v70n4/v70n4p49.pdf

[8] Ibid

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ira Katznelson When Affirmative Action Was White. WW Norton, 2006.

[11] For a more extensive historical and political analysis of how race has inhibited the development of a robust and centralized welfare state throughout American history, see Lieberman, R. C. (2001). Shifting the Color Line: Race and the American Welfare State (New edition). Harvard University Press.

[12] Dewitt, 57. Rodems, R., & Shaefer, H. (2016). Left Out: Policy Diffusion and the Exclusion of Black Workers from Unemployment Insurance. Social Science History, 40(3), 385-404. doi:10.1017/ssh.2016.11

[13] Katznelson, 132. Edwards, K. (2020, October 3). There are racial disparities in American unemployment benefits. that’s by design. Los Angeles Times.https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-10-03/racial-disparities-unemployment-benefit

[14] Ibid.

[15] Couch, K. A., & Fairlie, R. (2010). Last hired, first fired? Black-white unemployment and the business cycle. Demography, 47(1), 227–247. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0086

[16] Wilson, V., & Darity, W. (2022, March). Understanding black-white disparities in labor market outcomes requires models that account for persistent discrimination and unequal bargaining power. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/unequalpower/publications/understanding-black-white-disparities-in-labor-market-outcomes/

[17] Ibid.

[18] Weller, C. “African Americans Face Systematic Obstacles to Getting Good Jobs” (Washington: Center for American Progress, 2019), https://americanprogress.org/issues/economy/reports/2019/12/05/478150/african-americans-face-systematic-obstacles-getting-good-jobs/

[19] Nichols, A., & Schak, O. (2019). Degree Attainment for Black Adults: National and State Trends. Education Trust. https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Black-Degree-Attainment_FINAL.pdf

[20] Center for American Progress Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Current Population Surveys, 2019” (Washington: U.S. Department of Labor, 2019), available at https://www.bls.gov/cps/

[21] Ajilore, O. (2021). The Persistent Black-White Unemployment Gap Is Built Into the Labor Market. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/persistent-black-white-unemployment-gap-built-labor-market/

[22] Pager, Devah. 2007. “The Use of Field Experiments for Studies of Employment Discrimination: Contributions, Critiques, and Directions for the Future”. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 609 (Janurary):104-133.

[23] Kline, P., Rose, E. K., & Walters, C. R. (2022). Systemic Discrimination Among Large U.S. Employers. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(4), 1963–2036. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjac024

[24] Nellis, A., PhD. (2022). The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons. The Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/reports/the-color-of-justice-racial-and-ethnic-disparity-in-state-prisons-the-sentencing-project/

[25] Prison Policy (2022). New data on formerly incarcerated people’s employment reveal labor market injustices. Prison Policy Initiative. https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2022/02/08/employment/

[26] Gelles-Watnick, R., & Anderson, M. (2021). Racial and ethnic differences stand out in the U.S. gig workforce. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/12/15/racial-and-ethnic-differences-stand-out-in-the-u-s-gig-workforce/

[27] Long, H. (2021). How many Americans are unemployed? It’s likely a lot more than 10 million. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/02/19/how-many-americans-unemployed/

[28] Department of Labor. (2023). Significant Provisions of State Unemployment Insurance Laws. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/statelaws.asp

[29] Department of Labor Handbook on UI eligibility. Department of Labor. 2009. https://oui.doleta. gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2019/monetary.pdf

[30] Sprick, Emerson. How Is the Unemployment Insurance Program Financed? Bipartisan Policy Center, 15 Mar. 2022, https://bipartisanpolicy.org/explainer/how-is-the-unemployment-insurance-program-financed/

[31] In addition to each of the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands also operate their respective insurance agencies.

[32] Mazzei, Patricia, et al . ‘Florida Is a Terrible State to Be an Unemployed Person’. The New York Times, 23 Apr. 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/23/us/florida-coronavirus-unemployment.html

[33] Farrell, Diana, et al, Consumption Effects of Unemployment Insurance during the Covid-19 Pandemic (July 16, 2020). http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3654274

[34] Gwyn, Nick. “State Cuts Continue to Unravel Basic Support for Unemployed Workers.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 27 June 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-cuts-continue-to-unravel-basic-support-for-unemployed-workers

[35] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statiistics. Median Usual Weekly Earnings of Full-time Wage and Salary Workers by Race, Third Quarter.18 October 2022. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/wkyeng.t03.htm

[36] Gelles-Watnick, R., & Anderson, M. (2021). Racial and ethnic differences stand out in the U.S. gig workforce. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/12/15/racial-and-ethnic-differences-stand-out-in-the-u-s-gig-workforce/

[37] Rachel West, et al. “Strengthening Unemployment Protections in America: Modernizing Unemployment Insurance and Establishing a Jobseeker’s Allowance,” Center for American Progress, National Employment Law Project, and Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality. Report, 2016). https://americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/UI_JSAreport.pdf

[38] Ibid.

[39] Chetty, Raj. 2008. Moral hazard versus liquidity and optimal unemployment insurance. Journal of Political Economy 116(2): 173-234. https://doi.org/10.1086/588585; Wandner, Stephen A., and Christopher J. O’Leary. 2018. “Unemployment Insurance Reform: Evidence-Based Policy Recommendations.” In Unemployment Insurance Reform: Fixing a Broken System, Stephen A. Wandner, ed. Kalamazoo, MI: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, pp. 131-210. https://doi.org/10.17848/9780880996532.ch5

[40] Weller, Christian. “African Americans Face Systematic Obstacles to Getting Good Jobs.” Center for American Progress. 25 April 2022. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/african-americans-face-systematic-obstacles-getting-good-jobs/

[41] Center for Budget and Policy Priorites. (2020). Applicants Who Receive Unemployment Insurance Have Less Hardship. https://www.cbpp.org/applicants-who-receive-unemployment-benefits-have-less-hardship

[42] Ganong, P., et al. (2021). Lessons Learned from Expanded Unemployment Insurance during COVID-19. In Recession Remedies (p. 83). Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/RR-Chapter-2-Unemployment-Insurance.pdf

[43] U.S. Census Bureau, Survey of Income and Program Participation, 2015-2019 (wave 3, May–August).

[44] Government Accountability Office. (2015). Unemployment Insurance: States’ Reductions in Maximum Benefit Durations Have Implications for Federal Costs. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-15-281.pdf

[45] Department of Labor Handbook on UI eligibility. Department of Labor. 2009. https://oui.doleta. gov/unemploy/pdf/uilawcompar/2019/monetary.pdf

[46] Ibid

[47] Government Accountability Office. (2015). Unemployment Insurance: States’ Reductions in Maximum Benefit Durations Have Implications for Federal Costs. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-15-281.pdf

[48] U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). 31.2% of Households Receiving Unemployment Insurance Report Having a Very Difficult Time Paying for Food, Rent, Other Household Expenses. Census.gov. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/03/despite-unemployment-insurance-many-households-struggle-to-meet-basic-needs.html

[49] Government Accountability Office. (2015). Unemployment Insurance: States’ Reductions in Maximum Benefit Durations Have Implications for Federal Costs. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-15-281.pdf

[50] Congressional Research Services. (2021). Unemployment Rates During the COVID-19 Pandemic. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R46554.pdf

[51] Congress created three Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), and Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) as temporary unemployment relief programs during the pandemic, amounting to over $650 billion in federal spending. All three programs expired in September 2021. See, Gwyn, N. (2022). Historic Unemployment Programs Provided Vital Support to Workers and the Economy During Pandemic, Offer Roadmap for Future Reform. https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/historic-unemployment-programs-provided-vital-support-to-workers-and-the-economy

[52] Unemployment Insurance Improvement Act, S.2865, 117th Congress. 2021. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2865/text

[53] Barr, A. (2022). December’s Jobs report reveals a growing racial employment gap, especially for Black women. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/the-avenue/2022/01/11/decembers-jobs-report-reveals-a-growing-racial-employment-gap-especially-for-black-women/

[54] Gwyn, Nick. “State Cuts Continue to Unravel Basic Support for Unemployed Workers.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 27 June 2022, https://www.cbpp.org/research/state-budget-and-tax/state-cuts-continue-to-unravel-basic-support-for-unemployed-workers

[55] Government Accountability Office. (2015). Unemployment Insurance: States’ Reductions in Maximum Benefit Durations Have Implications for Federal Costs. https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-15-281.pdf

[56] Average duration of unemployment in the U.S. 1990-2021. (2022). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/217837/average-duration-of-unemployment-in-the-in-the-us

[57] Weller, C. (2022). African Americans Face Systematic Obstacles to Getting Good Jobs. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/african-americans-face-systematic-obstacles-getting-good-jobs/

[58] Benefit levels: Increase UI benefits to levels working families can survive on. (2021). Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/section-5-benefit-levels-increase-ui-benefits-to-levels-working-families-can-survive-on/

[59] Currently, 28 have adopted the practice of indexing benefits to annual wage inflation. Importantly, only one Southern state, Texas, has adopted this practice.

[60] Thirty-three states, most notably California, and the Department of Labor rely on the ABC test to classify workers. The ABC test clearly defines the conditions under which a worker is an employee, making it easier for workers and employers to understand their rights and responsibilities. The three-prong test to classify a worker as an independent contractor is: the worker is free from the control and direction of the hiring entity in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of the work and in fact; The worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and the worker is customarily engaged in an independently established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as that involved in the work performed. See, ABC Test. (2022). California Department of Labor & Workforce. https://www.labor.ca.gov/employmentstatus/abctest/

[61] Donnan,S., et al. “Georgia shows just how broken American unemployment benefits are,” Bloomberg, November 19, 2021, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2021-georgia-unemployment-bias/.

[62] Herman, J. (2021). Increasing the Taxable Wage Base Unlocks the Door to Lasting Unemployment Insurance Reform. The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/commentary/increasing-taxable-wage-base-unlocks-door-lasting-unemployment-insurance-reform/

[63] The uniform method of high multiples does not consider the level of unemployment or the size of the workforce in a state, which can also affect the funding needs of a UI system. As a result, this can lead to a mismatch between the funding provided and the actual needs of a state’s UI system, resulting in underfunding or overfunding. See, Galle, Brian. 2019. “How to Save Unemployment Insurance.” Arizona State Law Journal 50: 1009–1064. https://arizonastatelawjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Galle-Pub.pdf

[64] Ibid.

[65] US Department of Labor announces funding to states to modernize the unemployment insurance system, combat fraud, and address equity. (2021). U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/newsroom/releases/eta/eta20210811

[66] See, Farren, M., & Kaiser, C. (2021). COVID-19 Expanded Unemployment Insurance Benefits May Have Discouraged a Faster Recovery. Mercatus Center. https://www.mercatus.org/students/research/policy-briefs/covid-19-expanded-unemployment-insurance-benefits-may-have

[67] Faberman, J., & Ismail, A. (2020). How Do Unemployment Benefits Relate to Job Search Behavior? Chicago Fed Letter, 441. https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/chicago-fed-letter/2020/441

[68] Ganong, P., et al. Spending and Job-Finding Impacts of Expanded Unemployment Benefits: Evidence from Administrative Micro Data (August 2022). NBER Working Paper No. w30315, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4190156

[69] Dube, A. (2021). A Plan to Reform the Unemployment Insurance System in the United States. Hamilton Project. https://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/A_Plan_to_Reform_the_Unemployment_Insurance.pdf

[70] For a compelling analysis of flaws of racial zero-sum politics and how structural racism negatively impacts everyone, including white Americans, see McGhee, H. (2022). The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together. Penguin Random House.