By Samantha Wilkerson, M.Ed., John R. Lewis Social Justice Fellow

Introduction

Education and economic inequity persist as profound challenges in major U.S. cities affecting Black and Brown youth. Without access to quality education, Black and Brown students face worse lifelong outcomes. When children do not have basic functional literacy, they experience hardships such as being less likely to gain employment (particularly skilled roles), less likely to earn a livable wage, and less likely to use preventative health services (Mulcahy et al. 2019). Relatedly, students who are not functionally literate are more likely to interact with the criminal justice system and experience depression (Mulcahy et al., 2019). Furthermore, the reliance on property taxes for school funding exacerbates disparities, as communities with lower property values often have less funding for their schools, perpetuating the cycle of educational inequity. This Capstone addresses housing disparities as a contributor to educational inequity and demands urgent attention and comprehensive solutions from the federal government to simultaneously tackle both housing and education disparities. This research assignment delves into the persistent challenges of education and economic inequity faced by Black and Brown youth in major U.S. cities (Mulcahy et al., 2019). The profound impact of limited access to quality education on the lifelong outcomes of Black and Brown students is evident, as functional literacy serves as a crucial determinant of their future prospects. The consequences of inadequate education range from reduced employability and lower wages to increased interactions with the criminal justice system and higher rates of depression (Mulcahy et al., 2019). The reliance on property taxes for school funding further exacerbates these disparities, perpetuating the cycle of educational inequity. This Capstone project aims to address housing disparities as a significant contributor to educational inequity, emphasizing the urgent need for comprehensive solutions from the federal government to simultaneously tackle housing and education disparities. Utilizing the BlackCrit Framework, which centers antiblackness, challenges the neoliberal-multicultural imagination, and advocates for Black liberatory fantasy, the research seeks to provide a nuanced understanding of the complex intersectionality of race, education, and housing, advocating for transformative changes to break the cycle of systemic inequity (Sexton, 2016; Rose, 2019).

Understanding Property Taxes in the U.S.

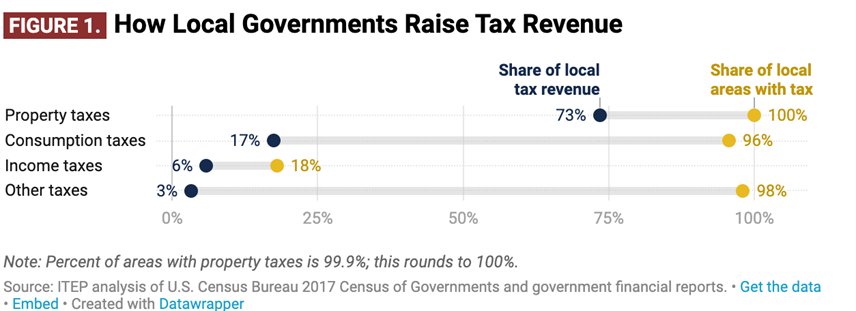

In the 20th century, property taxes evolved into a crucial revenue source for local governments, particularly for funding education and essential services. The early 1900s marked the emergence of property taxes as the primary revenue stream for state and local governments, constituting over 80% of state and local tax revenue and playing a pivotal role in financing public services, including education and infrastructure development (How Property Taxes Work, 2011). Historically, property taxes applied to two kinds of property: real property, which includes land and buildings, and personal property, which includes moveable items such as cars, boats, and the value of stocks and bonds. Despite the introduction of income and sales taxes at the state and federal levels in the mid-20th century, property taxes retained their significance in supporting local governance, with real property taxes becoming the dominant form from the latter half of the 20th century into the 21st century (Fisher, 2022).

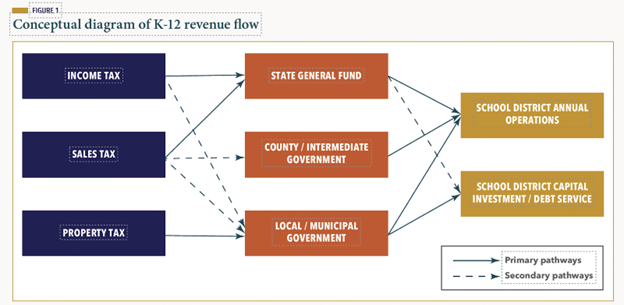

Today, real property taxes are instrumental in funding local governments and schools, contributing approximately 75% of local tax revenue nationwide (Fisher, 2022). This revenue supports a wide array of services, including education, police and fire protection, healthcare, and infrastructure. Housing appraisals determine property taxes. Property assessments—determining the market value of a property—follow a cyclical process based on state or local laws. Tax assessors employ methods such as sales comparison, cost method, and income method to calculate assessments, with the assessed value influencing the property tax amount. Challenges arise from inequities in property assessments and disparities in property values. Criticisms center on the contribution of property assessments to housing appraisal inequity, as they may not accurately reflect a property’s true value. Such disparities can result in uneven tax burdens on homeowners and exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities within Black and Brown communities. Recent studies, such as the work by Howell and Korver-Glenn (2020), shed light on the intricate relationship between housing appraisals, socioeconomic factors, and funding disparities. The research indicates that home characteristics, including house size and quality, as well as neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics, contribute to the inequality in home values between predominantly white neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color.

The research findings highlight a stark contrast in the trajectory of home values, with the average home value in white neighborhoods experiencing a substantial increase of $225,000 from 1980 to 2015. In contrast, communities of color witnessed a considerably smaller increase of $31,000 during the same period. This discrepancy underscores the persistent disparities in wealth accumulation and property values based on racial demographics. Metropolitan areas with higher Black and Latinx populations face a higher disparity in home values between white neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color. This correlation emphasizes the systemic challenges faced by communities of color in accessing equitable housing opportunities and quality services in their community that are based on local taxes.

The Evolution of Education Funding Disparities

Since the 1970s, local school districts in the United States relied on local property taxes as a primary funding source for public education and communities have raised concerns about the resulting disparities in the quality of education. This issue gained national attention, sparking a debate on equal access to educational opportunity. Serrano v. Priest (1971) in California marked a turning point, challenging the state’s reliance on local property tax and arguing that it disadvantaged students in lower-income districts (Stanford University, 1971). This recognition triggered a national debate on the importance of equal access to educational opportunity. The Court found that the state of California’s school finance system, which depended on local property taxes, violated the Equal Protection Clause due to significant funding disparities (Stanford University, 1971).

The Serrano case spurred a series of legal challenges across the country, including San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (TX, 1973), Robinson v. Cahill (NJ, 1973), Levittown v. Nyquist (NY, 1982), Abbott v. Burke (NJ, 1985-2011), and Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. State of New York (NY, 2001-2006). These cases collectively questioned the constitutionality of education finance systems heavily reliant on property taxes, asserting that they perpetuated inequalities in educational opportunities based on the wealth of the local community. Today, disparities persist despite legal interventions and changes to state control of school finances. Communities across the country are currently engaged in ongoing legal battles to secure equitable funding for their schools, emphasizing the enduring challenges associated with the historical reliance on local property taxes.

| Case | State | Argument | Outcome |

| Serrano v. Priest (1971-77) | California | Families argued that the California school finance system, which relied heavily on local property tax, disadvantaged the students in lower-income districts. | The Supreme Court of California ruled that the California system of funding public schools through local property taxes was discriminatory and unconstitutional, which they upheld in subsequent lawsuits. |

| San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (1973) | Texas | Parents argued that the school finance system in Texas, which relied on local property tax for funding beyond that provided by the state, disadvantaged the children whose districts were in poorer areas. | The Supreme Court found that the system did not violate the Equal Protection Clause after determining that the system did not intentionally or substantially discriminate against a class of people. |

| Robinson v. Cahill (1973) | New Jersey | Parents and families argued that the New Jersey public school funding system’s heavy reliance on local property violated the state constitution. | The New Jersey Supreme Court found that this system violated the state constitutional guarantee of access to a “thorough and efficient” public education system. |

| Levittown v. Nyquist (1982) | New York | Parents of low-income students of color claimed that New York State Finance System’s reliance on property taxes disadvantaged low-income students. | The court recognized the inequality; however, they ruled the disparity did not deprive low-income students of color of their right to education. |

| Abbott v. Burke (1985-2011) | New Jersey | New Jersey’s Education Law Center claimed that New Jersey’s school finance system both disadvantaged students in low-income districts and contributed to significant differences in the adequacy of education offered in poor districts compared to wealthy districts. | The New Jersey Supreme Court found the system unconstitutional and ordered that the state implement a program to ensure that funding in the “Abbott Districts” would be comparable to that of the wealthier districts. |

| Rose v. Council for Better Education (1989) | Kentucky | The Council for Better Education claimed that funding via property taxes failed to provide an efficient system of common schools throughout the state. | The Kentucky Supreme Court found the state school finance system in violation of the Kentucky constitution, formally recognizing adequate education as a fundamental constitutional right. The Court ordered the state to adhere to seven specific educational reform goals. |

| DeRolph v. State (1997) | Ohio | A coalition of representatives from 550 school districts in the state argued Ohio’s school finance system relied heavily on local property tax and contributed to disparities between wealthier and poorer school districts. | The Ohio Supreme Court called for decreased reliance on property tax and other reforms. However, the finance system was found unconstitutional several more times in subsequent cases DeRolph II and DeRolph III. The issues with school funding persist in Ohio to this day, despite the Supreme Court’s ruling. |

| Campaign for Fiscal Equity v. State of New York (2001-2006) | New York | The Campaign for Fiscal Equity argued that New York’s school finance system was unconstitutional because it failed to provide adequate funding to public schools, denying students access to the constitutionally guaranteed right to a basic education. | The Court of Appeals ordered the state to reform the system to ensure students would receive an adequate education. |

(Stanford University, 1971)

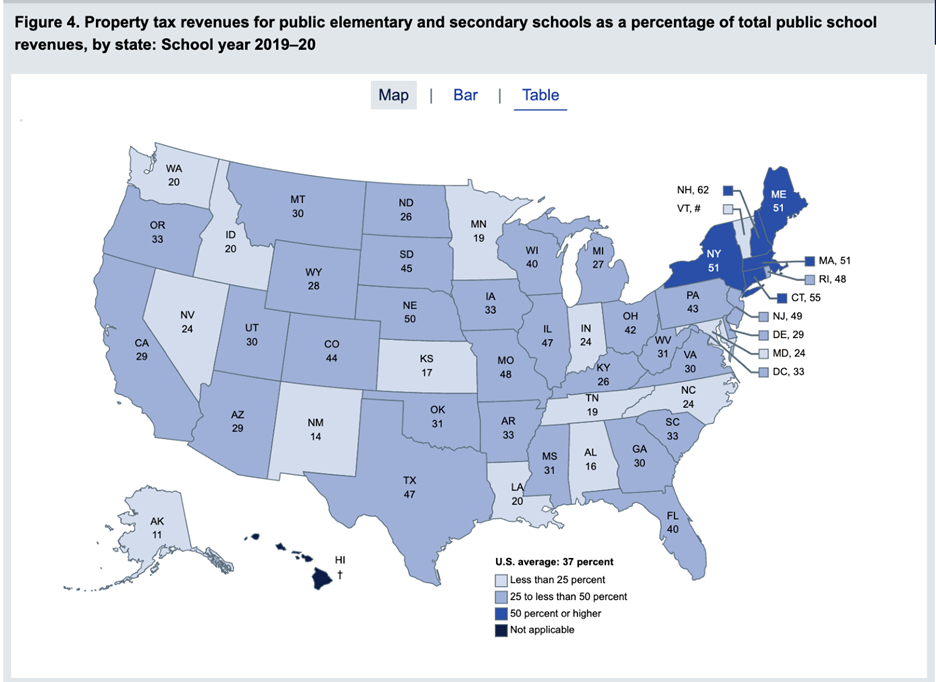

Following the reconning in the 1970s, the role of the local property tax in financing public education in the United States has remained stable—most states have not changed how they use property taxes to funding public schools. This stability has been attributed to the fact that local property taxes do not fluctuate as much as some other local and state taxes. From1988–1989, property taxes contributed 35.8% of total K–12 funding, a figure that slightly increased to 36.2% from 2018–2019. The resilience of the property tax base over time compared to income or taxable sales. Presently, real property tax rates vary widely across the country, with states using models involving property valuation, determination of taxable value, and application of tax rates. Unintended consequences of exemptions and deductions result in less taxable revenue for funding local schools, highlighting the need for policymakers to address these issues to achieve more equitable education funding.

(NCES, 2019)

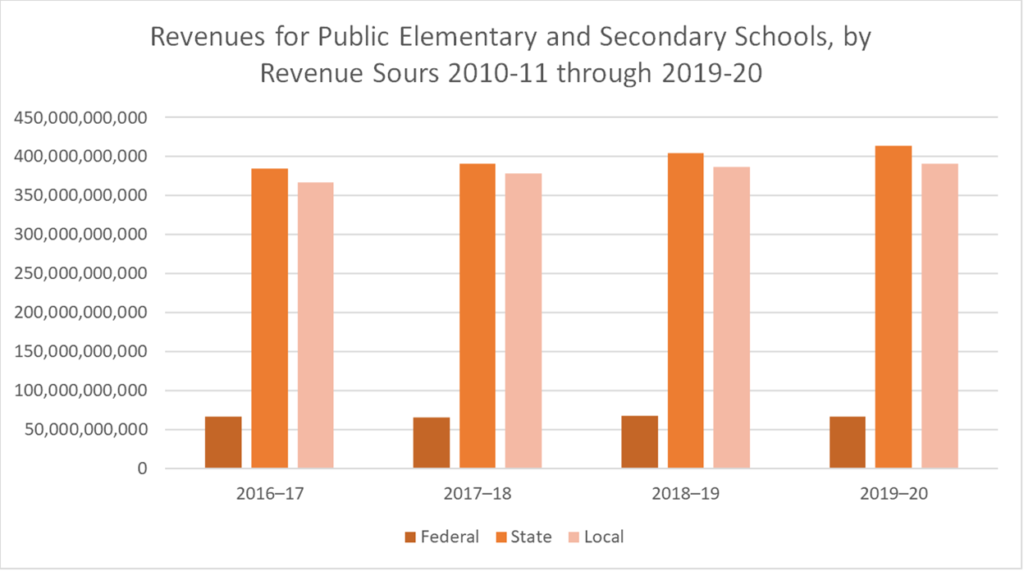

The reliance on property taxes to fund education has created an inequitable burden on communities, particularly those advocating for low property taxes to maintain housing affordability. In 2020, state and local governments collectively generated $600 billion in revenue from property taxes, constituting 17% of general revenue. While states collected $19 billion (1% of state general revenue), local governments, including school districts, amassed $581 billion (30% of local general revenue) from property taxes (Tilsley, 2017).

However, the reliance on property tax revenue varies among states, creating disparities in funding. Real property tax rates differ widely across the country. States employ various mechanisms to influence taxable values and taxpayer payments, including limits, exemptions, deductions, and credits, making it difficult to address inequity without some sort of federal oversight that aims to bridge the gap. Some states, like New Jersey, derive over 20% of their revenue from property taxes, burdening local communities. In contrast, states such as Louisiana collect less than 10% of their revenue from property taxes, resulting in a different financial landscape (elaborate?) (State and Local General Revenue, Percentage Distribution, 2023).

| 2020-21 School Year Total education funding: $837,337,948 (in thousands) Federal funding: $88,410,942 (in thousands), $1,797 per pupil, constituting 10.6% of total funding. State funding: $383,806,597 (in thousands), constituting 45.8% of total funding. Local funding: $365,120,409 (in thousands), constituting 43.6% of total funding. Property taxes contribute $301,559,895 (in thousands), constituting 36.0% of total funding. Other public revenue contributes $58,134,003 (in thousands), constituting 6.9% of total funding. Private funding: $5,426,510 (in thousands), constituting 0.6% of total funding. |

Source: (National Center for Education Statistics, 2023)

Academic Disparities and Funding Inequity

In general, local revenue from property taxes remains within the jurisdiction where it is raised, contributing to significant disparities in funding between wealthier and less affluent school districts (Baker et al, n.d.). This funding model allows wealthier districts to generate more school revenue even at lower tax rates, exacerbating educational inequalities. Education is widely recognized as a cornerstone for societal progress. However, persistent academic disparities between affluent and low-income students underscore a critical issue within the education system. Affluent students, privileged with greater access to educational resources, consistently demonstrate enhanced academic performance, higher graduation rates, and increased opportunities for advanced education. Conversely, low-income students face systemic barriers, including limited access to quality schools, resources, and extracurricular activities, resulting in lower academic attainment and graduation rates. Furthermore, many affluent districts, capable of raising substantial local revenue, often receive a share of state aid that exceeds their actual needs for adequate spending. This scenario frequently leads to the most affluent districts within a state receiving significantly more funding than higher-poverty districts, contributing to unequal opportunity gaps across the nation (Baker, Di Carlo, and Weber 2022).

The academic disparities faced by low-income students manifest in enduring consequences throughout their lives. Limited educational opportunities translate into reduced access to well-paying jobs and constrained career paths, perpetuating cycles of poverty and restricting upward mobility. Challenges in accessing higher education further limit opportunities for personal and professional growth. Academic achievement is intricately tied to socioeconomic status, creating a noticeable gap between affluent and low-income students. Evidence suggests that high-poverty districts may face inefficiencies in budget planning, particularly in human resource and personnel processes (Liu and Johnson 2006). These districts often struggle to fill teaching vacancies and hire late, potentially missing out on highly qualified candidates (Sorensen and Ladd 2020). Revenue volatility, rather than poor management alone, may play a significant role in these challenges. To address these disparities and their long-term consequences, targeted interventions are imperative. Equitable distribution of resources, increased access to quality education, and tailored support for low-income students through appropriate funding can effectively bridge the academic gap. This necessitates a comprehensive approach to reshape funding structures and prioritize educational equity.

Timeline of Significant Events in Housing and Education

1865: End of Slavery: The Civil War ends, and slavery is abolished with the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

1866: Civil Rights Act of 1866: The Act grants all citizens the same rights enjoyed by white citizens, including the right to own property.

1919-1939: Redlining Emerges: The practice of redlining begins as the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) maps neighborhoods based on racial composition, limiting mortgage lending to predominantly white areas.

1934: The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) is established to provide federal insurance on home loans, but it institutionalizes redlining practices.

1954: Brown v. Board of Education: The Supreme Court decision declares racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, challenging the “separate but equal” doctrine established by Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. This decision influenced discussions on racial equality in other areas, including housing.

1957: Little Rock Nine: Nine African American students are integrated into Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas, facing intense opposition, and demonstrating the resistance to desegregation.

1964: Civil Rights Act of 1964: Title VI prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance, including public schools.

1965: Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA): The ESEA is enacted to address educational inequalities by providing federal funding to schools serving low-income students.

1968: Fair Housing Act: The Fair Housing Act is signed into law, prohibiting discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, color, religion, or national origin.

1971: Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education: The Supreme Court upholds busing as a tool for achieving desegregation in public schools.

1974: Miliken vs Bradley: The 5-4 Supreme Court held that school district lines cannot be redrawn for to combat segregation unless the redrawn lines were the product of discriminatory acts by school districts.

1977: Community Reinvestment Act (CRA): The CRA is enacted to address discriminatory lending practices and encourage financial institutions to meet the credit needs of the communities in which they operate.

1990s-2000s:

Subprime Mortgage Crisis: Disproportionate targeting of minority communities leads to a wave of foreclosures, exacerbating existing disparities in homeownership.

De facto Segregation: Despite legal efforts to desegregate schools, de facto segregation remains a significant issue in many school districts, often reflecting neighborhood segregation patterns.

2001: No Child Left Behind (NCLB): NCLB emphasizes standardized testing to assess student performance and holds schools accountable for academic progress, but it also exacerbates educational inequalities.

2009: Housing and Economic Recovery Act: The Act includes provisions to address the foreclosure crisis and improve access to affordable housing.

2015: Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH): The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) implements a rule to strengthen the Fair Housing Act and promote housing equality.

2020:

COVID-19 Pandemic: The national pandemic highlights existing housing inequalities, with marginalized communities disproportionately affected by job losses and housing insecurity.

Black Lives Matter Protests: Protests against racial injustice draw attention to systemic inequalities, including those in housing, prompting renewed efforts to address housing equity.

Remote Learning Disparities: Remote learning during the pandemic highlights disparities in access to technology and resources, disproportionately affecting students in low-income communities.

2023: Ongoing Efforts for Equity: Various initiatives, policies, and community-led efforts continue to address educational disparities and promote equity in public education. The state of public education remains a dynamic and evolving landscape. Communities across the country are fighting to combat gentrification and unfair housing practices.

Effects of Redlining, Segregation, and Gentrification on School Districts

The complex relationship between property tax, housing inequity, and public education in the United States is deeply rooted in history, creating a tapestry of systemic disparities that persist to this day. The early reliance on local property taxes in the American education system inadvertently established an unequal educational landscape, laying the foundation for ongoing systemic disparities. Examining the historical timeline, particularly key events, and legislation, unveils the intricate connection between housing inequity and educational disparities.

The journey begins in 1865 with the end of slavery, a pivotal moment marked by the ratification of the 13th Amendment. The reluctance of many to fully accept the freedom of Black individuals prompted the enactment of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. This pivotal legislation granted all citizens, regardless of race, the same fundamental rights, including the right to own property, previously enjoyed exclusively by whites. Despite these legislative efforts the emergence of redlining perpetuated discriminatory practices in housing. Redlining is the practice of systematically denying mortgages, loans, and lines of credit to Black people (Egede 2023). The Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) mapped neighborhoods based on racial composition, limiting mortgage lending to predominantly white areas. While neighborhood segregation was widely accepted, some community advocates believed that desegregating schools was pivotal for Black students, so that they could have access to quality education. The landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954 declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, challenging the doctrine of “separate but equal.” This influential decision not only transformed education but also influenced discussions on racial housing equality as neighborhoods began to change with the desegregation of schools. However, the resistance to desegregation, exemplified by the Little Rock Nine in 1957, underscored the challenges faced in achieving genuine integration. The rise of activism and anti-discrimination protests that characterized the early1960s lead to new legislation aimed at combating racism. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation that emerged in response to decades of racial discrimination and segregation in the United States. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 further addressed discrimination by prohibiting it based on race, color, or national origin in programs and activities receiving federal financial assistance, including public schools. Simultaneously, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 aimed to rectify housing discrimination, but its impact fell short of eliminating the deeply rooted issues caused by redlining and discriminatory housing practices.

In the 1970s, the Supreme Court decisions in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education and Miliken v. Bradley navigated the complexities of desegregation, with the latter decision emphasizing the challenges in redrawing school district lines for combating segregation. Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board aimed to hasten the pace in which schools were being integrated, stating that busing was a valid way to integrate schools and combat segregation. However, this did not address the issue of neighborhood segregation and was ultimately made moot by the Miliken v. Bradley decision. Miliken v. Bradley decided that school districts could not be drawn with the specific purpose of desegregation unless it was clear that the district was segregated because of intentional discriminatory acts. The impact of this decision is evident today with school districts more segregated today than they were in 1990 (Pendharkar, 2023).

There is a similar trend in housing. Following several laws, such as the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, that sought to address discriminatory lending practices, disparities persist. The 1990s and 2000s witnessed the subprime mortgage crisis, which disproportionately affected minority communities and exacerbated existing disparities in homeownership. Efforts were made in the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2009 to address the foreclosure crisis and improve access to affordable housing. Considering modern-day issues, the intertwining of income segregation, housing access, and educational disparities becomes even more pronounced when considering racial bias in housing practices. The segregation related to income and housing access creates starkly different environments between high-income and low-income districts, exacerbating existing disparities. White families are often able to find housing in more affluent districts than Black families, even when their incomes are identical. Discriminatory housing practices persist, as evidenced by studies indicating that Black families may live in lower-income areas than white families with identical incomes (Reardon et al. 2015).

Gentrification, marked by the influx of middle-class white residents into lower-income Black and Brown communities, introduces a new layer of challenges for public schools. The rise of school choice legislation amidst gentrification exacerbates the disruption to neighborhood schools. As wealthier families exercise the option to send their children to schools outside the local district through school choice programs, the neighborhood schools experience a decline in enrollment and subsequent divestment. This trend disproportionately disadvantages Black and Brown students, as the changing demographics fail to align with increased investments in local educational institutions.

High-income Black families are more likely to reside in less affluent neighborhoods than their white counterparts (Owens 2018). The disparities extend beyond income levels, with Black households consistently living in lower-income neighborhoods compared to white households of similar income levels across the board (Logan 2011; Reardon et al. 2015). These inequities are fueled by racial discrimination and prejudice in the housing market, differences in wealth across racial lines, and racially stratified residential preferences (Pattillo 2005). Moreover, Black middle-class neighborhoods tend to be geographically closer to low-income neighborhoods, a phenomenon not mirrored in white middle-income neighborhoods (Sharkey 2014). The complexity deepens as school districts encompass larger geographic areas than single census tracts. Therefore, Black middle- or high-income families may find themselves residing in predominantly lower-income school districts, even when they live in higher-income neighborhoods. The interconnected nature of housing inequity and educational disparities demands comprehensive and sustained efforts to dismantle systemic barriers and pave the way for a more equitable future. Addressing racial bias in housing practices is crucial for fostering not only a fairer housing market but also a more just and inclusive education system.

Current Landscape, etc.

Across the United States, a concerning trend emerges as districts with higher proportions of students of color consistently receive substantially less state and local revenue compared to districts with fewer students of color. This disparity highlights the continuity of systemic inequities in present day educational funding. In the 2019–20 school year, 24 states relied predominantly on state government funding, 17 states and the District of Columbia primarily on local government funding, and 9 states lacked a single dominant revenue source (NCES 2019). Property taxes are the largest single source of revenue for most districts in the nation. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, during the 2019-2020 school year 81% of all local funding for education came from property taxes.

In many Black and Brown neighborhoods, homes are appraised at values lower than their actual worth; Black neighborhoods are valued roughly 21% to 23% below what their valuations would be in non-black neighborhoods (Perry& Rothwell 2022). This discrepancy in property values translates to a profound funding disparity in public schools, where districts serving a majority of students of color receive 16% less state and local revenue compared to districts with fewer students of color (Morgan, 2022). This financial shortfall hampers the educational opportunities and outcomes for Black and Brown youth. The economic disparity is most noticeable in metropolitan areas where the intersections of gentrification, segregation, and redlining worsen these challenges.

(NCES 2021)

(National Center for Education Statistics, 2022)

Quality public education systems have the power to ameliorate the issues plaguing Black and Brown young people; however, it requires a fully funded public education system. Since 2020 Schools across the nation have suffered budget cuts on the heels of the Covid-19 pandemic, and student outcomes continue to suffer (Hechinger Report, 2020). Currently, the House of Representatives Appropriations Committee has proposed cutting over 80% of federal funding to K-12 education, widening the gap in underserved school districts (Barnum, 2023).

Persistent funding gaps in American schools disproportionately impact low-income students of color. The revelation that the wealthiest 25% of school districts spend $1,500 more per student than the poorest 25% underscores the systemic inequalities embedded within the education system (American University, 2020). By relying heavily on property taxes for school funding, which inherently varies between affluent and impoverished areas, school districts perpetuate funding disparities from the outset. This fundamental flaw leads to a stark reality where affluent areas have well-funded schools while low-income areas grapple with inadequately funded educational institutions. District sizes further compound funding discrepancies. Predominantly white districts are often smaller in size and receive $23 billion more than districts predominantly serving students of color (EdBuild, 2016). This funding disparity not only reflects the structural biases in resource allocation but also contributes to the perpetuation of racial and socio-economic inequalities. The consequence is that children in need of additional support to overcome barriers to academic achievement are consistently shortchanged, creating a systemic hindrance to their educational success.

An analysis of national spending data in schools across the United States revealed that 53 districts spend a statistically significant lower amount of state and local money on high-poverty schools compared to lower-poverty schools (Hechinger Report, 2020). In an additional 263 districts, the spending levels show little to no correlation with the number of students in poverty, ignoring the heightened needs often present in low-income schools. This is significant because studies have proven that low-income students need additional support to have their needs met in school. Affluent districts that are smaller, better funded, and predominantly white, consistently outperform lower-income districts across the states (NAEP 2022). This disparity is not merely an academic concern; it is deeply rooted in discriminatory housing practices, low income, and limited mobility factors such as access to public transportation. The barriers faced by Black and Brown families in moving into these affluent districts create a stark contrast in opportunities for educational success.

The smaller size of these affluent districts plays a pivotal role in shaping the learning experience. With better funding and fewer students, these districts can provide a higher quality of education and support. The result is a notable difference in academic achievement, creating a cycle where better outcomes lead to more resources, further perpetuating the educational advantage of these districts. The nexus between discriminatory housing practices, educational funding disparities, and academic outcomes is undeniable. The impact of funding gaps on the quality of education received by students in different districts highlights the urgent need for comprehensive reforms.

Spotlight: Miami

Miami, Florida, grapples with a stark educational divide shaped by a funding model that disproportionately favors affluent neighborhoods, perpetuating systemic inequalities. Areas such as Coral Gables benefit from elevated property tax revenue, enabling schools to offer advanced STEM programs, extracurricular activities, and robust counseling services. In stark contrast, neighborhoods like Liberty City face significant challenges with deteriorating school infrastructure, outdated resources, and limited access to technology, further amplifying educational disparities. Florida’s education landscape ranks 45th in the nation in terms of fiscal effort to fund schools (Gutierrez, 2023). Miami serves as a notable example of the detrimental impact of gentrification on Black and Brown communities, with roots tracing back to the 1960s construction of Interstate 95. This project displaced over 10,000 people in historically Black communities like Overtown, setting the stage for future gentrification (Race, Housing, and Displacement in Miami, 2020). In contemporary times, the gentrification crisis unfolds as rising property prices in Wynwood trigger a ripple effect, drawing developers’ attention to neighboring Little Haiti. With approximately 82% of Little Haiti residents being renters, they become susceptible to increased rent prices and the looming threat of displacement (U.S. Census). The gentrification of Miami compounds long-standing challenges for residents, including displacement, inadequate transportation, and limited access to quality healthcare. While education funding in Florida, where the federal government contributes 11%above the national average (NCES 2022)—theoretically offers some relief, the systemic issues associated with gentrification persist, exacerbating disparities in educational outcomes for Black and Latino students. Miami students, while outperforming counterparts in other large cities, still face significant disparities, with Black and Latino students scoring 37 and 18 points, respectively, below their white peers in Reading on the most recent NAEP exams. The case of Miami underscores the multifaceted impact of gentrification on public schools and the broader community, necessitating a nuanced and comprehensive approach to address the systemic inequalities that persist. The intersection of education finance, gentrification, and racial disparities requires urgent attention to create an equitable and inclusive educational landscape for all Miami students.

Spotlight: Trenton

Trenton, New Jersey, grapples with stark educational disparities rooted in a school funding formula heavily reliant on local property taxes. Affluent neighborhoods, notably West Trenton, benefit from higher property values, translating into well-funded schools equipped with state-of-the-art facilities, updated technology, and a diverse range of advanced placement courses. In contrast, economically disadvantaged areas, like East Trenton, face considerable challenges, including aging infrastructure, outdated textbooks, and larger class sizes, hindering students’ access to quality education. A report by Baker and Weber (2022) underscores the alarming disparities in New Jersey’s school systems, especially those with majority Black and Hispanic or Latinx students from low-income neighborhoods. These districts emerge as the most underfunded in the state, leaving educators struggling to provide quality education. In Trenton, the report reveals that without fully funding the school-aid formula, the spending gap per student would be nearly $22,000, further exacerbating the financial challenges faced by the school district. Black and Hispanic/Latinx children in communities with lower property values face systemic issues resulting in lower local capacity to raise revenues for schools. The deliberate racist practices of “redlining” and “block busting” have contributed to segregated communities with artificially lower property values. Importantly, these practices are not relics of the past; the generational wealth taken from residents of these communities continues to have profound effects on school funding today (Sitrin, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed and intensified these patterns of institutionalized racism, resulting in poverty-related education disparities and substantial racial inequities in school resources (Baker & Weber, 2021). The urgent need to address these systemic issues is underscored by the profound impact on the educational opportunities and outcomes of Trenton’s students. A comprehensive and equitable approach to school funding is imperative to break the cycle of disparity and ensure every student in Trenton receives the quality education they deserve.

Spotlight: Detroit

Detroit, Michigan, epitomizes stark education disparities, notably driven by a funding model intricately linked to local property taxes. Affluent neighborhoods, exemplified by areas like Grosse Pointe, enjoy substantial funding, leading to well-equipped schools with modern technology, specialized programs, and experienced teachers. However, in neighborhoods such as Brightmoor, challenges persist with deteriorating school infrastructure, outdated resources, and a shortage of qualified educators, thereby intensifying the educational divide within the city. Michigan faced considerable challenges even before the COVID-19 pandemic. The impact of these challenges was further exacerbated during the pandemic, with students performing worse than many states. On the 2022 NAEP test, Detroit students’ average scale score dropped significantly more than the national average, and reading scores are now seven points lower than they were nearly two decades ago (NAEP). Addressing these disparities requires significant investments to close the funding gap, particularly for low-income students, English Learners, and students with disabilities. Michigan’s school funding formula has been criticized as one of the most regressive in the country (Tilsley, 2017). Research indicates that, on average, the state’s highest poverty districts receive 5% less state and local funding than the lowest poverty districts, despite serving a student population with significantly greater needs. Michigan’s funding system was inequitable and inadequate, with per-pupil funding declining by 22 % between 2002 and 2015 when adjusted for inflation, according to a report from Michigan State University. As of 2024, districts are navigating the final year of spending federal relief funding allocated for COVID-19 recovery. The end of this critical funding poses a risk to many districts, especially given the ongoing post-pandemic crises affecting student achievement, attendance, and mental health, as indicated by state and national data. Without additional state investments, districts face a potential average cut of $1,200 per student in the 2024-25 school year due to declining enrollment and the cessation of the Elementary and Secondary Emergency School Relief (ESSER) funds. This funding loss will impact higher poverty districts the most, threatening critical needs that have been supported by these funds. Last year Michigan took a historic step with the Opportunity Index, a weighted funding formula designed to invest more in districts with higher concentrations of poverty, however the state has not committed to fully funding the recommended amount. To close the funding gap and effect transformative change, it is crucial to fully fund the Opportunity Index, ensuring up to 47% more investment for students in districts with the highest concentrations of poverty.

Spotlight: St. Louis

In St. Louis, Missouri, educational disparities are starkly evident, driven by a funding model heavily reliant on local property taxes. Affluent neighborhoods, exemplified by places like Clayton, benefit from smaller class sizes, well-maintained facilities, and a rich array of extracurricular activities. Unfortunately, this contrasts sharply with areas like North St. Louis, where resource shortages, larger class sizes, and insufficient investment in teacher professional development contribute to significant disparities in academic achievement and future opportunities for students. An in-depth analysis of all 24 St. Louis County and St. Louis City public school districts unveils a concerning trend related to economic development tax abatements, particularly tax increment financing (TIF). Over the past six years alone, these abatements have cost students in the St. Louis area more than a quarter of a billion dollars (With et al., 2024). The financial impact is devastating for students, with St. Louis area schools losing at least $260.7 million to tax abatements in the six fiscal years from 2017 through 2022, with a disproportionate burden on students of color. On average, white students lose $179 per year, while their Black counterparts lose more than three times that amount – $610 per year (With et al., 2024). TIF emerges as the costliest abatement program, affecting both St. Louis Public Schools and all schools countywide (With et al., 2024). To address these systemic issues, many advocates recommend shielding school funding from the impact of tax abatements. This can begin to rectify the financial disparities that perpetuate educational inequalities in St. Louis.

The gravity of the situation becomes even more apparent when examining standardized test performance. According to Missouri state data, public schools in St. Louis rank poorly on standardized tests, with white children being five times more likely than Black children to attend schools where meeting math and language arts standards is the norm (St. Louis City School District (2020-21) | Saint Louis, MO, n.d.). Amid these challenges, there emerges a beacon of hope in the form of ActivateSTL, an initiative started by Tiara Jordan-Sutton, a Black woman who, having attended mostly white schools, recognized the stark differences in educational experiences. Now, she is dedicated to empowering Black parents in St. Louis to advocate for equitable access to quality educational resources for their children (ACTIVATE STL, n.d.). This grassroot effort exemplifies the resilience and determination within the community to address the root causes of educational disparities and work towards a more equitable future.

In Miami, Florida, Trenton, New Jersey, Detroit, Michigan, and St. Louis, Missouri, educational disparities are glaringly evident, shaped by funding models heavily reliant on local property taxes. Affluent neighborhoods benefit disproportionately, enjoying well-equipped schools with modern facilities and technology, while economically disadvantaged areas face aging infrastructure, outdated resources, and larger class sizes. These disparities are exacerbated by systemic issues such as gentrification and deliberate racist practices like redlining and blockbusting, which have perpetuated segregated communities with artificially lower property values.

In Miami, gentrification compounds long-standing challenges, displacing communities and exacerbating educational disparities. Despite Florida’s above-average federal education funding, Black and Latino students still lag behind their white counterparts in academic performance. In Trenton, New Jersey, the school funding formula exacerbates disparities, with majority Black and Hispanic/Latinx students in low-income neighborhoods facing underfunded schools. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exposed and intensified institutionalized racism, widening poverty-related education disparities. In Detroit, Michigan, disparities persist due to regressive funding formulas, with high-poverty districts receiving less funding despite greater student needs. Without additional investments, districts face significant funding cuts, threatening critical needs and exacerbating disparities. Similarly, in St. Louis, Missouri, tax abatements disproportionately burden students of color, exacerbating educational inequalities. Despite challenges, grassroots efforts like ActivateSTL demonstrate resilience and determination within communities to address systemic issues and advocate for equitable access to quality education.

The cases of Miami, Trenton, Detroit, and St. Louis underscore the urgent need for comprehensive and equitable approaches to education funding. Shielding school funding from the impact of tax abatements, fully funding recommended amounts, and investing in districts with higher concentrations of poverty are crucial steps toward addressing systemic inequalities and creating an inclusive educational landscape for all students.

Policy Recommendations

The landscape of education in the United States is marred by persistent disparities, particularly evident in the funding models linked to local property taxes. Wealthier districts, buoyed by their ability to raise substantial funds locally, stand in stark contrast to their less affluent counterparts grappling with lower tax rates. This dichotomy, underscored by academic achievement gaps between affluent and low-income students, is a critical issue demanding comprehensive policy solutions. This Capstone delineates a set of recommendations advocating for an enhanced role of the federal government in education funding. By addressing the intricate relationship between housing and education, redefining resource allocation criteria, expanding federal funding, and introducing innovative measures, the research proposes a holistic approach to mitigate disparities and foster educational equity.

- HUD and ED Collaboration – Joint Task Force: Congress should pioneer the establishment of a joint task force between the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Department of Education (ED). This collaborative effort aims to holistically address property value issues arising from affordable housing programs, ultimately impacting school funding. By fostering synergy between these two departments, a comprehensive approach can be developed to address housing and education disparities simultaneously.

- Redesign Title I Allocation: The Department of Education should champion a redesign of Title I allocation, specifically targeting communities with the most vulnerable students. This would look like simplifying the application process and redesigning grant disbursement to ensure that the largest percentage of funding goes to school districts with the highest percentages of students in need. This policy solution seeks to direct federal resources to school districts facing the most significant challenges, ensuring that funds are allocated where they are needed most and promoting equity in education.

- Expand Federal Education Funding: Legislators should advocate for an expansion of federal education funding, focusing on communities historically impacted by redlining and those successful in lawsuits related to the Fair Housing Act of 1968. This initiative aims to rectify the enduring effects of historical injustices by providing additional resources to communities that have faced systemic barriers.

- Voucher System for Under-Served Communities: The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) should introduce a voucher system as a supplementary measure to counteract low property appraisals in underserved communities. This system aims to provide additional financial support to schools in areas where property values are disproportionately low, ensuring that underfunded schools have the necessary resources to deliver a high-quality education.

In conclusion, these policy recommendations emphasize the imperative for an enhanced federal role in education funding. By fostering collaboration between HUD and ED, redesigning Title I allocation, expanding federal funding, and introducing a voucher system, we can strive towards dismantling systemic barriers, fostering educational equity, and creating a more inclusive and just educational landscape for all students. These initiatives represent a bold step forward in the pursuit of a fair and equitable education system, acknowledging the pivotal role of the federal government in shaping the future of our nation’s learners.

References

ACTIVATE STL. (n.d.). ACTIVATE STL. Retrieved January 24, 2024, from https://www.activatestl.org/

American University. (2020, September 10). Inequality in Public School Funding | American University. Soeonline.american.edu. https://soeonline.american.edu/blog/inequality-in-public-school-funding/#:~:text=By%20relying%20largely%20on%20property

Baker, B. D., Di Carlo, M., & Oberfield, Z. W. (2023). The Source Code: Revenue Composition and the Adequacy, Equity, and Stability of K-12 School Spending. https://www.shankerinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/REVreport_final.pdf

Baker, B., & Weber, M. (2021, September 13). Separate and Unequal: Racial and Ethnic Segregation and the Case for School Funding Reparations in New Jersey. New Jersey Policy Perspective. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/separate-and-unequal-racial-and-ethnic-segregation-and-the-case-for-school-funding-reparations-in-new-jersey/

Baker, B., & Weber, M. (2022, February 2). New Jersey School Funding: The Higher the Goals, the Higher the Costs. New Jersey Policy Perspective. https://www.njpp.org/publications/report/new-jersey-school-funding-the-higher-the-goals-the-higher-the-costs/

COE – Public School Revenue Sources. (2022, May). Nces.ed.gov. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cma/public-school-revenue

EdBuild. (2016). EdBuild | 23 Billion. Edbuild.org. https://edbuild.org/content/23-billion

Egede, L. E., Walker, R. J., Campbell, J. A., Linde, S., Hawks, L. C., & Burgess, K. M. (2023). Modern Day Consequences of Historic Redlining: Finding a Path Forward. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 38(6). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08051-4

Fisher, R. (2022). September 2021 Property Taxes: What Everybody Needs to Know Working Paper WP21RF1.

Florida, R., & Pedigo, S. (2019). TOWARD A MORE INCLUSIVE REGION Inequality and Poverty in Greater Miami REPORT. https://carta.fiu.edu/mufi/wp-content/uploads/sites/32/2019/04/Final-Brief-Toward-a-More-Inclusive-Region.pdf

Gutierrez, B. (2023, January 10). Disparate public-school funding greatly affects students’ achievements. News.miami.edu. https://news.miami.edu/stories/2023/01/disparate-public-school-funding-greatly-affects-students-achievements.html

How Property Taxes Work. (2011, August 11). ITEP. https://itep.org/how-property-taxes-work/

Howell, J., & Korver-Glenn, E. (2020). The Increasing Effect of Neighborhood Racial Composition on Housing Values, 1980–2015. Social Problems. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa033

Logan, J. R. (2011). Separated and Uequal: The Neighborhood Gap for Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians in Metropolitan America. Boston, MA: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston.

Mathewson, T. G. (2020, October 31). New data: Even within the same district some wealthy schools get millions more than poor ones. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/new-data-even-within-the-same-district-some-wealthy-schools-get-millions-more-than-poor-ones/

Morgan, I. (2022, December). Equal Is Not Good Enough: An Analysis of School Funding Equity Across the U.S. and Within Each State. Edtrust.org. https://edtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Equal-Is-Not-Good-Enough-December-2022.pdf

Mulcahy, E., Bernardes, E., & Baars, S. (2019). The relationship between reading age, education and life outcomes LKMco -The education and youth “think and-action” tank. https://cfey.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/The-relationship-between-reading-age-education-and-life-outcomes.pdf

Owens, A. (2017). Income Segregation between School Districts and Inequality in Students’ Achievement. Sociology of Education, 91(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040717741180

Pendharkar, E. (2023, June 7). Public Schools Are Still Segregated. But These Tools Can Help. Education Week. https://www.edweek.org/leadership/public-schools-are-still-segregated-but-these-tools-can-help/2023/06

Perry, A., & Rothwell, J. (2021, November 17). Biased appraisals and the devaluation of housing in Black neighborhoods. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/biased-appraisals-and-the-devaluation-of-housing-in-black-neighborhoods/

Prosperity Now. (2016, October). Racial Wealth Divide in Miami. Prosperitynow.org. https://prosperitynow.org/sites/default/files/resources/Racial_Wealth_Divide_in_Miami_RWDI.pdf

Race, Housing, and Displacement in Miami. (2020, November 2). ArcGIS StoryMaps. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/0d17f3d6e31e419c8fdfbbd557f0edae

Reardon, S. F., & Bischoff, K. (2011). Income Inequality and Income Segregation. American Journal of Sociology, 116(4), 1045–1056. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429494642-104

Rix, K. (2023, December 12). St. Louis Advocacy Group Trains Parents, Students to Improve Struggling Schools. The74million.org. https://www.the74million.org/article/st-louis-advocacy-group-trains-parents-students-to-improve-struggling-schools-2/

Roda, A., & Steward Wells, A. (2013, February). School Choice Policies and Racial Segregation: Where White Parents’ Good Intentions, Anxiety, and Privilege Collide. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.1086/668753.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A991614cd28825d3429e65311e0062feb&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&origin=&initiator=search-results&acceptTC=1

Samms, B. (2022, March 21). Racial Discrimination in Home Appraisals Is a Problem That’s Now Getting Federal Attention. ITEP. https://itep.org/racial-discrimination-in-home-appraisals-is-a-problem-thats-now-getting-federal-attention/

Serrano v. Priest. (n.d.). EdSource. https://edsource.org/glossary/serrano-v-priest#:~:text=A%20California%20court%20case%2Dbegun

Sharkey, P. (2014). Spatial Segmentation and the Black Middle Class. American Journal of Sociology, 119(4), 903–954. https://doi.org/10.1086/674561

Sitrin, C. (2020, October 3). New Jersey spent 35 years and $100B trying to fix school inequity. It still has problems. POLITICO. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/10/03/new-jersey-school-inequity-problems-425494

St. Louis City School District (2020-21) | Saint Louis, MO. (n.d.). Www.publicschoolreview.com. https://www.publicschoolreview.com/missouri/st-louis-city-school-district/2929280-school-district

Stanford University. (1971). Landmark US Cases Related to Equality of Opportunity in K-12 Education | Equality of Opportunity and Education. Edeq.stanford.edu. https://edeq.stanford.edu/sections/section-4-lawsuits/landmark-us-cases-related-equality-opportunity-k-12-education

State and Local General Revenue, Percentage Distribution. (2023, July 7). Tax Policy Center. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/statistics/state-and-local-general-revenue-percentage-distribution

The Adequacy and Fairness of State School Finance Systems 2024. (2024, January). School Finance Indicators Database. https://www.schoolfinancedata.org/the-adequacy-and-fairness-of-state-school-finance-systems-2024/

Tilsley, A. (2017, May). School funding: Do poor kids get their fair share? Urbn.is. https://apps.urban.org/features/school-funding-do-poor-kids-get-fair-share/#:~:text=Public%20schools%20are%20funded%20through

With, A., Barish, J., & Leroy, G. (2024). Overarching Disparities: How Black and Poor Students are Disproportionately Impacted by St. Louis-Area Tax Abatements. https://goodjobsfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Overarching-Disparities-How-Black-and-Poor-Students-are-Disproportionately-Impacted-by-St.-Louis-Area-Tax-Abatements-.pdf