By Cameryn Blackmore

Introduction

Mental health in the United States is a salient issue that has been gaining the attention of both policymakers and citizens, especially since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In recent years, there has been an increased focus on the mental health of America’s youth. Mental health concerns[1] in children are diagnosed when there are drastic changes to the way a child typically learns, behaves, or handles their emotions (CDC, 2022). According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (2022), one in six youth in the country experiences a mental health disorder each year. The National Institute of Mental Health (2022) named suicide the second leading cause of death among youth ages 10-34. This trend is increasingly becoming a public health crisis. As mental health illness and suicide in American students rise, the need to reimagine mental health supports in schools, where students spend a significant amount of time, is necessary.

Schools as the Cornerstone

This capstone demonstrates the need to increase mental health services and personnel in school districts across the country and argues that mental health professionals should be primarily responsible for addressing the social and emotional needs of students. It further offers a discussion of school resource officers, and how the Jennings School District in Missouri reimagined the role of school resource officers to best serve its students. Every American student should have access to services that ensure they are accurately diagnosed and receive quality mental health care. The COVID-19 pandemic coupled with social unrest stemming from the George Floyd and Breonna Taylor murders makes the need for increasing mental health availability crucial, especially for school districts serving high numbers of Black and Brown students and students whose families may have lived through financial ruin following the onset of the pandemic.

School is the primary access point for students since every community has a school, and students spend a significant amount of time in school (Rossen & Cowan, 2015). The pandemic exposed the inadequacies of the mental health services landscape within public education. The impact of challenges faced by American students can be mitigated by an increase of support in the public education arena. Given the significant time educators and school staff spend with students, schools are the ideal settings to implement mental health supports. Unfortunately, many American students are experiencing a lack of access to qualified mental health professionals that can provide proper support.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020, school practitioners and mental health professionals were advocating for an increase in mental health services. Since pandemic began, an increase in school closures, virtual learning, social distancing, and mounting loss (mortality and financial) created great mental health strain for youth matriculating through school. The Centers for Disease Control conducted a survey of private and public-school students in the 9th through 12th grades and found high levels of poor mental health and feelings of hopelessness. According to the CDC, in 2021 37% of students surveyed reported experiencing poor mental health during the pandemic (Jones et al., 2022). The survey also found 44% of students experienced feelings of sadness and hopelessness during the 12 months before the survey (Jones et al., 2022). According to Rossen and Cowan (2015), 150 students out of 750 high school students will experience a mental illness that interferes with their learning behavior. Of those 150 high school students, about 100 of them did not gain access to professional help (Rossen & Cowan, 2015).

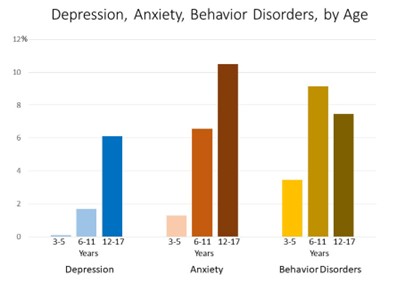

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Change with Age. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html

In addition to the pandemic, the number of school-wide mass shootings, often carried out by young people, has further heightened the mental health debate in the country. During the writing of this project, the country experienced the school shooting tragedy in Uvalde, Texas where 19 children and 2 teachers were shot by an 18-year-old (Harper and Beeferman, 2022). Though dissension existed regarding framing the shooting as a gun reform issue or mental health issue, the age of the shooter suggests more can be done within educational settings to provide support to students.[2] It is important to note people with mental illnesses make up only 5% of mass shootings (Columbia University, 2022).

For Black students, mental health resources are often nonexistent due to lack of access to adequate healthcare. According to Mental Health America (2019), major depressive episodes and suicide attempts in Black teens increased with suicide attempts increasing 73% between 1991 and 2017. Black teens are more likely to experience depression, but less likely to receive treatment (Klisz-Hulbert, 2020). This makes the need to have mental health services in public schools especially crucial for Black students.

The American Psychological Association (2022) supports a multi-level interdisciplinary approach to servicing the mental health needs of students in educational settings. This approach identifies the resources and stakeholders that must be active at every level to ensure the needs of students are met. At the school level, teachers must be equipped with strategies to support students’ social and emotional development (APA, 2022). Community is the second level of the interdisciplinary approach and consists of violence prevention programs administered through community recreational centers or churches (APA, 2022). The last level of the interdisciplinary approach is systematic, where the coordination of services in health, juvenile justice, education, and child protection systems occurs (APA, 2022).

The Discourse Around Mental Health in American Schools

Mental health has always been a concern within educational environments. Debates around the discriminatory practices of mental health diagnosing along racial lines and discussions stemming from the increase of school shootings are examples of issues covered within the mainstream media and academia mental health discourse. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 rapidly brought the stress on America’s youth to the forefront of mental health discussions. Isolation stemming from virtual schooling exposed the necessity of mental health supports in the educational environment. Additionally, the rise of societal problems, such as influx of crime, financial problems complicated by fallout from the pandemic, teacher shortages throughout the country, and the rise in the use of social media, also illustrate why mental health services within schools are important.

Increasing trends towards mental health issues in America’s youth have been tracked by the Centers for Disease Control. Between the years 2009 and 2019, there was a 44% increase in suicide plans reported among teens (Centers for Disease Control, 2021). While male students are often the topic of discussions in mental health due to the likelihood of male students experiencing more behavioral problems in school, female students are experiencing rising trends of mental health struggles. The survey also found more female students were likely to consider suicide and were injured in a suicide attempt from 2009 through 2019 (Centers for Disease Control, 2021). Similarly, of the students within the report that disclosed feelings of sadness or hopelessness 46.6% were female.

The rising trends in suicide planning and attempts were reported prior to school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which demonstrates the dire need for mental health resources and personnel to be made available within school environments. These trends have negative implications for adolescents, who are in their prime developmental years. Increased risk of drug use, unplanned pregnancy, and higher risk of unhealthy sexual behaviors are the threats associated with mental health problems in youth (Centers for Disease Control, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic will likely exacerbate the current trends and numbers associated with poor mental health in youth resulting in an increase in the percentages of students reporting mental health difficulties.

Decreasing trends associated with mental health problems in youth can be accomplished through increasing mental health support in schools. School serves as the main space for students to receive healthcare with students being 21 times more likely to receive school-based healthcare treatment than treatment in any other setting (Juszczak, Melinkovich, & Kaplan, 2003). Greater access to mental health services and professionals will ensure students have the treatment needed to lower current trends observed in youth. Lack of access to mental health professionals and services has negative implications for students. Students without proper access to mental health services are more prone to have trouble coping with circumstances at school and in their home lives. This can lead an increased use of negative coping mechanisms such as, drug use, sex, and participation in delinquent activities. These activities can lead to students having problems matriculating through school, which can ultimately stunt social mobility post-secondary education.

Access to screenings for the sake of accurate mental health diagnoses is a benefit of having mental health professionals in school. Anxiety, depression, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder (CD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Tourette syndrome, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and post-traumatic stress disorder are the common mental health disorders observed in children (CDC, 2022). Often, mental health in children is not prioritized in the same ways as physical illness (ex. Asthma), especially if the problems do not cause class disruptions (Lynch et al., 2015).

Lack of access to screenings that can properly diagnose children, especially children from marginalized backgrounds (socioeconomic, racial), leads to an underdiagnosing of mental health conditions like ADHD. When treated properly these conditions can result in positive educational and behavioral outcomes. Black children are less likely to receive an ADHD diagnosis than their white counterparts (Frye, 2022). For Black children diagnosed with ADHD, only 36% were taking medication for the condition (Frye, 2022). According to the American Psychological Association (2022), about 20 million children are diagnosed with a mental health disorder. Yet only 20% of children needing mental health services receive proper assistance from a mental health professional (APA, 2022). Access to mental health professionals and services can not only ensure students are properly diagnosed, but also ensure they receive proper treatment daily.

Anxiety and depression are additional common mental health diagnoses for children. Depression and anxiety in children can cause intense moods, which have increased due to the pandemic (Gleason & Thompson, 2022). Depression is defined as “sadness or irritability for two or more weeks” (Gleason & Thompson, 2022). Anxiety is defined by Gleason and Thompson (2022) as “problematic fear or worry.” Over the past five years, anxiety and depression has risen in children between 5 and 17 years old though mental health support did not increase over the same period (Osorio, 2022). In 2020, 5.6 million students had an anxiety diagnosis while 2.4 million had a depression diagnosis (Osorio, 2022). It is not only the more drastic mental health conditions impacting children, but intense worrying and sadness is increasing the likelihood of suicide.

Adverse Childhood Experiences and Student Supports

Supporting students through life challenges, also referred to as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), is perhaps the most significant way mental health professionals are useful within school settings. Adverse childhood experiences are defined by the CDC (2021b) as “traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years).” These events also include factors within a child’s environment that can disrupt a child’s sense of safety and stability (CDC, 2021b). Though experts consider several experiences ACEs, the Integrative Life Center (2021) lists ten categories for ACEs:

- Physical Abuse

- Sexual Abuse

- Emotional Abuse

- Physical Neglect

- Emotional Neglect

- Mental Illness

- Incarcerated Relative

- Mother Treated Violently

- Substance Abuse

- Divorce

In each category, specific circumstances can occur within a child’s life to impact their ability to maintain their mental health, which can lead to the child underperforming in school. For example, within physical neglect a student may be experiencing homelessness due to extenuating factors that can benefit from having access to a social worker.

Adverse childhood experiences are widespread problems school faculty and staff find themselves addressing every year. According to the CDC (2021b), about 61% of adults across 25 states have reported experiencing at least one ACEs before 18. Furthermore, the CDC (2021b) has linked ACEs to chronic illness and other negative life outcomes, such as heart disease, diabetes, suicide, poor educational and job attainment, and sexually transmitted diseases. Addressing ACEs requires intervention on behalf of a professional or dedicated adult to ensure students get the proper resources and coping skills to navigate their challenges.

Prevention of adverse childhood experiences is possible and requires support from professionals trained to treat mental health diagnoses. The CDC (2019) released a report detailing the best practices for preventing ACEs. Both mentoring through in school and after school activities along with intervention through treatment programs were two of the recommended strategies (CDC, 2019). In school, mental health professionals serve to treat and mentor students through their challenges. The CDC (2019) highlighted Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS), which was designed to provide treatment for students with limited access to services, as a strategy employed to provide students with needed treatment.

CBITS is “designed to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and behavioral problems, as well as to improve functioning, grades and attendance, peer and parent support, and coping skills” (Center for Resiliency, Hope, and Wellness in Schools, 2022). The program is delivered by mental health professionals, who are trained by a team of mental health professionals and consists of both group and individual in school therapy sessions (Center for Resiliency, Hope, and Wellness, 2022). CBITS was evaluated by the National Institute of Justice Crime Solutions (2011), which found the intervention program to be effective for lowering post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in students receiving treatment.

School districts in every state in the country are operating with less than the recommended number of healthcare professionals. It is recommended that school counselors provide services to no more than 250 students (American School Counselor Association, 2021). In the United States, the average school counselor to student ratio is about 1 to 390 (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019). Further, according to Mental Health America (2021), no state in the country meets the recommended ratio of 800 students to 1 social worker. This is troubling for both students and school based mental health staff that are managing increased loads of students.

School environments are often safe havens for students seeking relief from troubles in their home lives. The goal for school-based health practitioners and relevant stakeholders is to design and sustain health promoting school systems nationally. The World Health Organization (2021) defines a health promoting school as “a school that is constantly strengthening its capacity as a healthy setting for living, learning, and working.” Since school is where students spend a large portion of time, it is the ideal location for health services. The health promoting school concept is a whole school approach that considers the landscape of educational spaces to act as environments that can foster physical, social-emotional, and psychological health outcomes (World Health Organization, 2021). This approach envisions the school environment as a healing space with the proper resources and personnel to address the mental health concerns of students.

Funding educational programs and healthcare services is a challenge for school districts in high poverty areas. Often school districts are forced to make tough resource allocation decisions that may result in inadequate funding for mental health services and personnel. Funding from the federal government, American Rescue Plan, provided additional funding in local government budgets to assist with mental health recovery following the onset of the COVID-19 budget. However, school districts must ensure the programs they design are sustainable.

These challenges are amplified in school districts with smaller budgets that must make tough decisions about which services to offer students. Since public school districts receive a substantial portion of their funding from property taxes collected in their jurisdictions, the relationship between funding and student services offered in districts are correlated. School districts in high income areas can provide student services beyond those required by law, while school districts in high poverty areas can barely provide those resources and personnel required by law (ex. Certified teachers, textbooks).

Funding for School Resource Officers or Counselors?

Questions regarding school finances have been a hot button topic among advocacy groups, citizens, and stakeholders. To have adequate mental health professionals and services, funding must be available to provide treatment to students regardless of income qualifications. There has been much debate regarding the proper use of educational budgets. Organizations, like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP, 2020), have called upon school districts to defund school resource officers (SROs) to divert funding towards restorative services. Additional funding for mental health services in school would lead to more students having additional support during societal turmoil and their educational journeys.

Since the Columbine shooting in 1999, the United States has experienced several mass shootings on school grounds. The uptick of school shootings has led to much debate about the proper framing of the problem. Liberal leaning citizens view school shootings as gun reform issue, while conservative leaning citizens view the problem as a mental health problem. Though mental health has been mentioned within the policy debates, there has not been a major push to divert school funding from supporting SROs in schools to mental health professionals.

The focus on the school shooters has drawn much debate about the need for mental health support services, especially in school settings. Vossekuil et al. (2002) reported 34% of school shooters received a mental health evaluation with 17% receiving a mental disorder diagnosis. These numbers do not reflect the 78% of school shooters who reported suicide attempts or suicidal ideations prior to carrying out their attacks.

A significant number of school shootings in the country have been committed by assailants during their teenage years. Seven of ten school shootings have been carried out by people under the age of 18 since 1999 (Smith, 2022). Despite the shootings being carried out by teenagers, in both the Parkland[3] and Uvalde[4] school shootings law enforcement and SROs were unable to prevent the shooters from killing multiple students and teachers. Opponents of SROs in schools cite these instances to illustrate the ineffectiveness of SROs and argue for resources proven to be beneficial to students.

The National Association for School Resource Officers (n.d.), a nonprofit organization considered to be the leader in school policing, argues for the need to have school resource officers within schools to increase school safety. According to the organization’s website, training is offered to prepare school resource officers for serving students beyond law enforcement capacities. Not every school resource officer receives the training the National Association for School Resource Officers provides due to a lack of uniformity in placing school resource officers within districts.

Origins of School Resource Officers

The origins of school resource officers can be traced back to the 1950s based upon the need to have safe school environments for students in Flint, Michigan (Johnson, 1999). Societal shifts created an increased need for school resource officers. During the 1960s and 70s in the South, school resource officers were utilized to decrease racial tensions within schools (Coons and Travis, 2012). The presence of school resource officers expanded largely in the 1990s due to increases in juvenile crime rates, the Columbine school shooting in 1999, and federal intervention in community policing efforts (Sawchuk, 2021).

There are two pieces of legislation that resulted in an uptick of school resource officers during the 1990s. The Safe and Drug Free Communities Act passed in 1989 called upon school resource officers to help “(a) educate students in crime and illegal drug use prevention and safety, (b) develop community justice initiatives for students, and (c) train students in conflict resolution, restorative justice, and crime and illegal drug use awareness (Ryan et al., 2018).” Then in 1994, the crime bill established the Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) hiring program resulting in an increased number of school resource officers through grants funded by the Department of Justice (Sawchuk, 2021). Though federal intervention greatly increased the presence of school resource officers, the federal government does not issue mandates regarding the use of school resource officers.

Each state and local jurisdiction is responsible for outlining how school resource officers will be used within their school districts. According to Ryan et al. (2018), the “lack of policies regulating roles and responsibilities” is a factor in challenges created by using school resource officers. This finding is backed by a 2005 study conducted by the National Institution of Justice that determined the lack of clearly written roles and responsibilities for the school resource officer programs as a major challenge (Finn et al., 2005). Furthermore, in some local jurisdictions the schools or districts hold no autonomy regarding who is placed as an officer within the school (Ryan et al., 2018). As a result, school resource officer data collection is complicated since the information is held solely by law enforcement agencies in some areas (Sawchuk, 2021).

Who Is Responsible for School Safety?

Creating equitable school environments where every student feels supported despite any identifying factors should be a top priority of faculty, parents, and community stakeholders. Though school resource officers are tasked with creating safer school environments, Ryan et al. (2018) identified unintended consequences of school resource officers as it relates to negative interactions between students and officers and increases in referrals to the juvenile justice system for offenses. In 2011, a Justice Policy Institute report found schools with school resource officers had five times as many arrests for disruptive conduct than schools without them (JPI, 2011). Often the students referred to juvenile justice systems are students of color. According to an Education Week report, in 43 states and the District of Columbia Black students are disproportionately arrested in schools (Sawchuk, 2021).

According to Brady (2010), tasking school resource officers with managing student misbehavior has transformed traditional school disciplinary issues into criminal matters thereby contributing to the school-to-prison pipeline. The school-to-prison pipeline greatly impacts Black students, who are more likely to be arrested in schools (Blad and Harwin, 2017). According to the Office of Civil Rights within the Department of Education (2017), Black students are likely to attend schools with a presence of police. During the 2017-2018 school year, there was a 5% increase in the number of school related arrests with referrals to law enforcement increasing by 12% (Office of Civil Rights, 2017).[5]

Scholars have sought to study the relationship between school resource officers and student outcomes. School culture complicates the exploration into the effectiveness of school resource officers (Sawchuk, 2021). Ultimately, principals are responsible for the final student discipline outcomes. The National Association of School Resource Officers (n.d.) states more than one third of the arrests their officers made in schools were referrals initiated by school staff. In school mental health professionals could reduce in school arrests by providing students with social and emotional supports that are not purely punitive in nature.

According to the American Civil Liberties Union (n.d.), about 14 million students attend a school with the presence of a police officer but no healthcare professionals (counselor, nurse, psychologist, or social worker). These students have no access to healthcare professionals that are readily available to address their healthcare needs, but instead face law enforcement officers that have the autonomy to arrest them as they see fit with permission from school administrators. This is especially true for students with disabilities, who were 2.9 times more likely to be arrested in school than students without disabilities (ACLU, n.d.). Black students are also more likely to be arrested, with Black students being 8 times more likely to be arrested at school in some states than white students (ACLU, n.d.).

Despite the trends of inequity in punishment experienced by students with disabilities and Black students, SROs self-report positive experiences within school settings. Mielke (2021) surveyed SROs who reported high levels of collaboration with school officials and mental health professionals. Some SROs even reported being trained to address mental health challenges. However, SROs should not serve to replace mental health professionals within schools. While school safety is important, increasing school mental health professionals must be prioritized by school districts.

Reimagining Student Supports

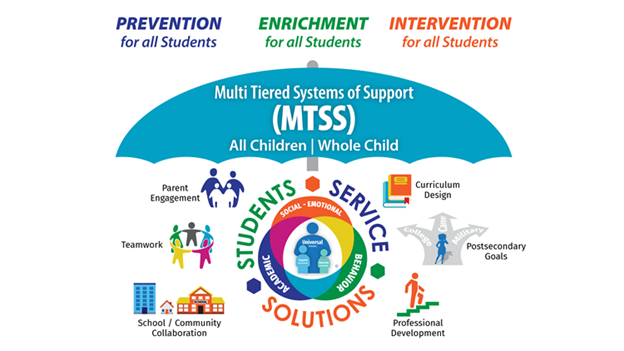

There are different frameworks designed to help schools and districts address the social and emotional needs of students. The Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS) “is a systematic, continuous improvement framework in which data-based problem solving and decision making is practiced across all levels of the educational systems for supporting students” (Riverside County Office of Education, n.d.). This framework allows for the implementation of student support services across three tiers with the assistance of partnerships with key community stakeholders. The Jennings School District is an example of a school district that has created student centered support services around the needs of the students utilizing collaborative partnerships with community stakeholders.

Source: Education Service Region 11. Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS). Retrieved from https://www.esc11.net/Page/8512

The Multi-Tiered System of Support has three tiers designed to address the needs of all students within the educational environment based on individual needs. The first tier, called the universal wellness promotion and primary prevention tier, addresses the needs of all students by prioritizing the application of social and emotional support across the school or district (Rossen & Cowan, 2015). The goal of the first tier is to create a supportive school environment for every student. The second tier, referred to as targeted prevention and intervention, addresses specific problems at the school level. This tier focuses on ensuring certain student groups or group problems are resolved using specialized support services (Rossen & Cowan, 2015). The third tier is called the individual/tertiary intervention and focuses on both indirect and direct student level mental health services (Rossen & Cowan, 2015). MTSS helps school districts manage and organize resources to best support students (Riverside County Office of Education, n.d.).

The Case of the Jennings School District

The Jennings School District, a suburb of St. Louis, Missouri, increased its mental health supports for both students and faculty immediately following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The school district consists of over 3,000 K-12 students. Jennings is a predominantly Black school district where 100% of the students receive free and reduced lunch, which is often an indicator for low-income students (Tutt, 2022). Of all the students in the Jennings School District, 98% are Black, 1% is Hispanic, and 1% is white. In 2016, the former superintendent, Dr. Art McCoy, reimagined the mental health services in his district.[6] He increased student services to serve students in the district during his tenure with a large portion of the additions being in the mental health space. Dr. McCoy utilized President Obama’s Promise Zone[7] definition and standards to evaluate the success of his efforts, though they also fit into the MTSS framework. The Jennings School District utilizes community partnerships to offer nontraditional wraparound services often not viewed as resources a school district is responsible for providing to students. Through their success, the school district has constructed a supportive school environment implemented across the district that serves all students regardless of the severity of their needs.

Since 2016, Jennings School District has prioritized health services. The COVID-19 outbreak made the need for mental health services throughout the district a dire need. Since 2020, the school district hired additional therapists for both students and teachers following the physical return to school face to face. Healing and safety centers were added to every school to create spaces for students and faculty to combat any pressures they encountered throughout the day. Mindfulness practices, such as yoga three times a day, were added to the daily schedule for every student. These resources and practices are available to all students and faculty within the district. In addition to providing access to mental health professionals and practices, the Jennings School District has also developed other programs to assist students meet their needs beyond social and emotional needs.

Jennings Senior High School opened a health clinic on campus in 2017 that employed physicians and nurses. Currently, the school district has two health clinics that provide students with a wide range of services from physical examinations, reproductive health, and management of chronic conditions (Jennings School District, 2022). This increases the accessibility of healthcare services for students. Jennings has filled the healthcare gap by offering healthcare services right on school grounds. Washington University oversees operations of the two healthcare clinics in the district.

Furthermore, Jennings offers access to two homeless shelters operated by local nonprofits for students and their families displaced by the pandemic. Homelessness is an adverse childhood experience, so it is imperative for school districts to address the need for shelter. Homeless students rarely receive screening for mental health conditions, despite being more likely to experience risk factors that lead to mental health problems (Lynch et al., 2015). Offering mental health screenings through homeless shelters has been identified as a practical approach (Lynch et al., 2015). The partnership between the homeless shelters and the Jennings School District allows for an intervention that stabilizes student living arrangements, so they can focus on their schoolwork and receive access to professional assistance.

Additionally, the Jennings School District operates a grocery store to address the food desert within the community. Students and their families have access to the grocery store, which operates on an incentive system. Attendance and improved performance in school is used as leverage to grant access to the grocery store. Ensuring students have housing and food, which are basic survival needs for humans, helps to make the Jennings School District a success story. The Maryland Food Bank has partnered with Giant supermarket to place food pantries in 155 schools. These programs help to provide additional support to students that may go home and not have enough food to eat.

Perhaps the greatest service offered to students upon graduation from the school system is found within the School to Work program. Students in the Jennings School District can either earn an associate’s degree or work at a paid internship their senior year. This prepares students to be attractive for jobs paying livable wages out of school. This program has been replicated in the St. Louis School District and is called the Earn and Learn program. The program in St. Louis offers four career pathways and currently has 120 interested businesses wanting to provide paid internships to St. Louis public school students. Workforce development is an important aspect of social mobility, and the St. Louis region of Missouri is ensuring students are prepared for any career they choose upon graduation. Of all the programs implemented by Dr. McCoy in the Jennings School District, the School to Work program is the most replicated program.

Sustainability of student support services is key to offering efficient and effective programs. Two key advantages of MTSS have been achieved within the Jennings School District and places the district in a great position to maintain sustainability. The school district has maintained “collaboration between general and special education,” and the school district has also “facilitated coordination with community providers while also ensuring that services provided are appropriate in the learning context” (Rossen & Cowan, 2015). Dr. McCoy envisioned his role as a superintendent beyond the expected requirements of operating the schools within the district. His entrepreneurial approach helped him raise $2 million in private funds through fundraising efforts to launch the new student support services. Currently, a large portion of the wraparound services are outsourced. Only $1 million is needed from private funding to ensure the upkeep of the services implemented during Dr. McCoy’s tenure.

Interdisciplinary approach to student services in the Jennings School District also includes the criminal justice field. While many school districts utilize SROs to manage student behavior, Jennings School District use SROs as a last resort to address student behavior. The school district required police in the schools to receive trauma-informed training and required that all arrests be approved by school administrators. The superintendent did not allow any SROs to use weapons on school grounds to guarantee de-escalation is the only method used on the students. With all these additional supports in place, the Jennings School District went from a D to an A rated district.

Policies Addressing Mental Health Services in Schools

Policymakers at every level of government should be concerned about ensuring students have proper access to mental health services. Congress has taken steps to expand mental health services within schools. During the 117th Congress (2021-2022), the House passed the Mental Health Services for Students Act of 2021 introduced by Representative Grace Napolitano. This bill would allocate grant money to support mental health services in schools, which include screening, treatment, and outreach programs. Though it passed the House of Representatives, the Senate has not vote to pass this act yet.

The FY 2022-2023 Omnibus has added money for an increase in mental health funding. The American Hospital Association (2022) announced the government provisions to healthcare, which included several provisions for mental health. An increase of $530 million to mental health programs, including those targeted to children and youth, was included within the Omnibus package.

While having an investment at the federal level is imperative, state and local governments should also invest in mental health services by earmarking funding for mental health supports in schools. Kansas has taken the necessary steps to invest in mental health services for their schools. The Kansas Mental Health Intervention Team Pilot Program increased mental health services with Kansas schools, and their state legislature has voted to increase funding for mental health services in schools.

Conclusion

Increasing mental health services in schools is necessary to ensure the next generation of Americans are fully equipped to become productive members of society. Preventing suicide in youth can be done through school based mental health support, but it must be prioritized by every level of government. Additionally, policymakers insisting on framing school shootings as a mental health issue should instead ensure the support and passing of legislation that promotes mental health services in schools.

The Jennings school district should serve as a model for every school district serving students that are marginalized due to their race or socioeconomic status. Following both the Multi-Tiered System of Support and employing an interdisciplinary approach to engage community partners should be encouraged within every community. Envisioning and reimagining mental health services and student support services in general is necessary to think outside of the box to resolve mental health challenges in youth. School board members should also consider diverting more funding into hiring mental health personnel and less into school resource officers who often employ punitive and harmful actions against students. If we are to lower the suicide rates of youth in the United States, mental health services in schools that support all students should be the ultimate goal.

References

American Civil Liberties Union. (n.d.). Cops and no counselors: How the lack of school mental health staff is harming students. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/030419-acluschooldisciplinereport.pdf

American Hospital Association. Senate passes omnibus spending package with health provisions. Retrieved from https://www.aha.org/2022-03-11-senate-passes-omnibus-spending-package-health-provisions

American Psychological Association. (2022). Children’s mental health. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/topics/child-development/mental-health

American School Counselor Association. (2012). ASCA national model: A framework for school counseling programs.

Brady, N. L. (2010). Circumventing the law: Students’ rights in schools with police. Journal of

Contemporary Criminal Justice, 26(3), 294–315

Centers for Disease Control. (2019). Preventing adverse childhood experiences: Leveraging the best available evidence. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/preventingACES.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021a). Mental health: Poor mental health is a growing problem for adolescents. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/mental-health/index.htm#:~:text=Mental%20Health%20Is%20A%20Growing%20Problem,-chart%20bar%20icon&text=More%20than%201%20in%203,a%2044%25%20increase%20since%202009

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021b). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/index.html

Centers for Disease Control. (2022). Children’s mental disorders. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/symptoms.html

Center for Resiliency, Hope, and Wellness in Schools. (2022). About CBITS. Retrieved from https://traumaawareschools.org/index.php/learn-more-cbits/

Columbia University Department of Psychiatry. (2022). Is there a link between mental health

and mass shootings? Retrieved from https://www.columbiapsychiatry.org/news/mass-shootings-and-mental-illness-5

Coon, J. K., Travis, L. F. (2012). The role of police in public schools: A comparison of principal

and police reports of activities in schools. Police Practice and Research, 13(1), 15–30.

Finn, P., Shively, M., McDevitt, J., Lassiter, W., Rich, T. (2005). Comparison of program

activities and lessons learned among 19 school resource officer (SRO) programs (Doc. No.

209272). Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/209272.pdf

Frye, D. (2022). The children left behind. ADDitude: Inside the ADHD Mind. Retrieved from https://www.additudemag.com/race-and-adhd-how-people-of-color-get-left-behind/

Gleason, M. & Thompson, L. (2022). Depression and anxiety disorder in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(5)

Harper, K. & Beeferman, J. (2022). Uvalde was a mental health desert before a school shooting prompted Texas to respond with resources. The Texas Tribune. Retrieved from https://www.texastribune.org/2022/06/16/uvalde-shooting-mental-health/

Integrative Life Center. (2021). What are the 10 adverse childhood experiences. Retrieved from https://integrativelifecenter.com/what-are-the-10-adverse-childhood-experiences/

Jennings School District. (2022). Student Support Services. Retrieved from https://www.jenningsk12.org/studentsupport

Johnson, I. (1999). School violence: The effectiveness of a school resource officer program in a

Southern city. Journal of Criminal Justice, 27(2), 173–192

Jones, S. et al. (2022). Mental health, suicidality, and connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic- Adolescent behaviors and experiences survey, United States, January-June 2021. Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/su/su7103a3.htm

Juszczak, L, Melinkovich, P., & Kaplan, D. Use of health and mental health services by adolescents across multiple delivery sites. Journal of Adolescent Health, 32(6), 108-118

Lynch, S. et al. (2015). Feasibility of shelter-based mental health screening for homeless children. Public Health Reports, 130(1), 43-47

Mental Health America. (2021). Addressing the youth mental health crisis: The urgent need for more education, services, and supports. Retrieved from https://mhanational.org/sites/default/files/FINAL%20MHA%20Report%20-%20Addressing%20Youth%20Mental%20Health%20Crisis%20-%20July%202021.pdf

Mental health by the numbers. (2022). National Alliance on Mental Illness. Retrieved from https://www.nami.org/mhstats

Mielke, F., Phillips, J., & Sanborn, B. (2021). Collaboration and juvenile mental illness. Community Policing Dispatch, 14(2)

NAACP New Bradford. (2020). Defund SROs: Put real resources in our schools. Retrieved from https://naacpnewbedford.org/2020/07/defund-sros/

National Association for School Resource Officers. (n.d.). About NASRO. Retrieved from https://www.nasro.org/main/about-nasro/

National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). Mental health staff in public schools, by school racial and ethnic composition. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019020.pdf

National Institute of Justice Crime Solutions. (2011). Program profile: Cognitive behavioral intervention for trauma in schools (CBITS). Retrieved from

Niche. (2022). Jennings school district. Retrieved from https://www.niche.com/k12/d/jennings-school-district-mo/

Osorio, A. (2022). Research update: Children’s anxiety and depression on the rise. Retrieved from https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2022/03/24/research-update-childrens-anxiety-and-depression-on-the-rise/

Riverside County Office of Education. (n.d.). Multi-tiered system of support (MTSS). Retrieved from https://www.rcoe.us/departments/educational-services/instructional-services/multi-tiered-system-of-supports-mtss

Rossen, E. & Cowan, K. (2015). Improving mental health in schools. Retrieved from https://littletonpublicschools.net/sites/default/files/MENTAL%20HEALTH%20-%20Improving%20MH%20in%20Schools%202015.pdf

Ryan, J., Katsiyannis, A., Counts, J., & Shelnet, J. (2018). The growing concerns of school

resource officers. Establishing More Equitable School Systems in Schools, 53(3)

Sawchuk, S. (2021). School Resource Officers (SROs), Explained. Education Week

Suicide. (2022). National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/suicide#:~:text=Suicide%20was%20the%20second%20leading,there%20were%20homicides%20(19%2C141)

Tutt, P. (2021). Breaking the cycle of silence around Black mental health. Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/article/breaking-cycle-silence-around-black-mental-health

Whitaker, A. (n.d). Cops and no counselors: How the lack of school mental health staff is harming students. American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved from https://www.aclu.org/sites/default/files/field_document/030419-acluschooldisciplinereport.pdf

World Health Organization. (2021). Making every school a health promoting school: Global standards and indicators. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025073

[1] The author uses mental health concerns in students to encompass all of the disorders a student can be diagnosed with. This includes Anxiety, Depression, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Tourette Syndrome, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

[2] The author disagrees with the framing of mass shootings as a mental health issue, which is an argument made from the conservative side. However, the author believes that those who wish to frame mass shootings in this way must also be willing to fund programs accessible to students in public education for the benefit of increasing access to mental health services.

[3] The Parkland school shooting occurred on February 14, 2018, at Stoneman Douglas High School. It resulted in the murder of 17 people and 17 people injured.

[4] The Uvalde school shooting occurred on May 24, 2022, at Robb Elementary School. It resulted in 21 people killed and 17 people injured.

[5] The school-to-prison pipeline is a phenomena many scholars and community stakeholders identify as the mechanism increasing the likelihood of a student being introduced into the penal institution by the way of schools settings.

[6] Dr. Art McCoy is the former superintendent of the Jennings School District. He is responsible for designing, implementing, and sustaining the student support services established during his tenure. I interviewed Dr. McCoy on June 28, 2022 virtually via Zoom. The information he provided will be shared throughout this section.

[7] The Promise Zone Plan was President Obama’s plan for engaging local business across the country with improving conditions of urban areas in the United States.